‘Starry Field’ Tackles Family Secrets and Identity in Houston

Growing up, author and journalist Margaret Juhae Lee was told her grandfather was a criminal. As an adult, she discovered he was actually a hero.

When Margaret Juhae Lee and her family moved to northwest Houston in the 1970s, neighbors across the street saw her father assembling a bicycle and came over. Assuming that he couldn’t read English, they offered to read the instructions to him. “I was in second grade, and I was like, ‘My father is a PhD,’” Lee recalls. “That kind of stuff happened a lot.”

As one of the few Asian Americans in her area, Lee never felt like she belonged. People always asked her where she was “really from” even after she already told them she was from Houston. Lee grew up in Houston feeling unrooted. She didn’t even know who her grandfather was, and no one in her family ever spoke about him. All she knew was that he had been in prison in Korea.

Years later as a graduate student in journalism, Lee began investigating the truth behind her grandfather. That investigation has culminated in her new book, Starry Field: A Memoir of Lost History, more than 20 years in the making, published this March.

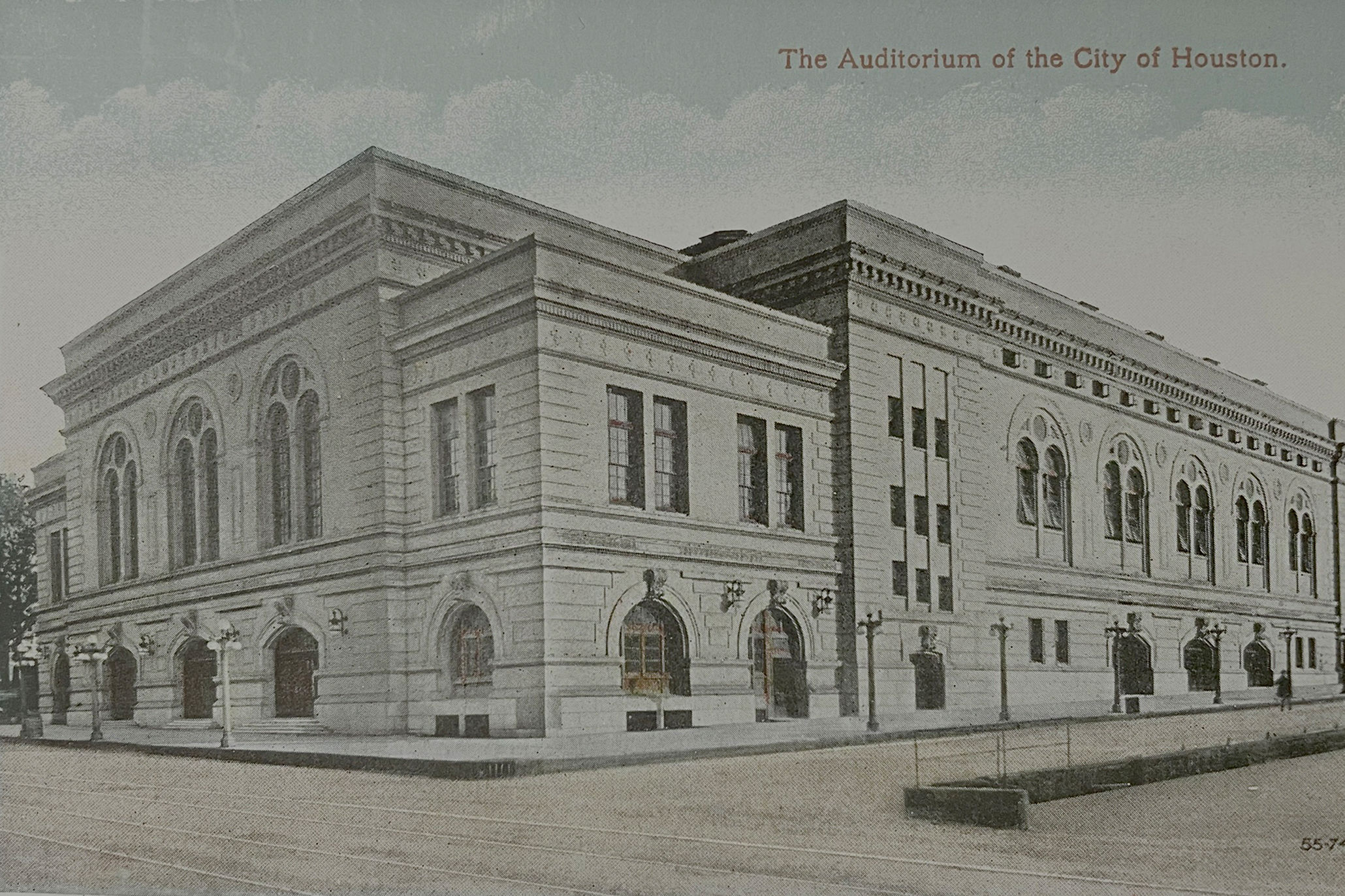

The memoir takes readers along as Lee travels to Seoul to interview her reluctant grandmother and look for records of her grandfather. Starry Field also gives glimpses of the Houston of Lee’s childhood, from trips to Luby’s for fried fish to Sunday afternoons spent in Houston Public Library’s downtown location reading back issues of magazines as disparate as Vogue and Creem.

While the book is about Lee’s search for her grandfather, it is also a search for herself. She discovers that her grandfather was a student revolutionary leader imprisoned by the Japanese for protesting their colonization of Korea. Rather than a criminal, he was a hero. Uncovering his story helps Lee’s family heal and finally brings her a sense of belonging.

We spoke to the author, who now lives in California, about her upbringing in Houston and how it shaped her.

This interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.

Houstonia: Your memoir is about the search for your grandfather. He died at 27 and your father didn’t know him. You describe not knowing him as a wound that was passed down to you. Can you speak to the inheritance of this wound?

Margaret Juhae Lee: I think now we would describe it as intergenerational trauma. When I started this book over 20 years ago, intergenerational trauma wasn’t a term that was much discussed. When I heard about it, I was like, “Oh my God. That’s what this is.” This absence of my grandfather's life was passed down to me: absence of history, absence of knowledge. And it really affected my father's identity, and therefore affected mine.

What I realized in writing this book over many years is that I didn’t want to pass that down to my own children. So, they know where their grandparents came from. They know who their great-grandparents were. And these were the stories of colonialism, or the war, that were not passed down to me because they’re so painful to my parents. They were just trying to survive. And I think that's true with a lot of immigrant families. The first generation that comes over here, they’re in survival mode. Their pasts are traumatic and painful, and they feel like it’s better for themselves and their offspring not to talk about it. But now we know that has a toll on the next generation.

What was the impetus for your family to move to the United States, and to Houston?

My parents came over in 1962 as graduate students—and this was before the majority of Korean immigrants came. So they came very early. I was born in 1966 in North Carolina where my dad was getting his PhD at North Carolina State. And then we moved to Houston in 1968, when I was 2. My father got a job at the School of Public Health, which is part of the UT system and is in the Medical Center. Originally, he thought that once he got his PhD, he would go back to Korea. But this tenure track job came up and he got it. So that’s why we went to Houston. We ended up living in Alief. And then we moved to the outer northwest suburbs, in Harris County, but near Tomball, near Willowbrook Mall, because that's how the markers in Houston are—by mall.

That's so true. As soon as you said Willowbrook Mall, I had a mental picture. Houston’s certainly diverse now, but it wasn’t as much in the ’70s and ’80s. What was it like for your family then?

We were basically treated like foreigners on a daily basis. There were very few people of Asian descent around. There was one other Korean family in the neighborhood. My high school had probably less than 10 Asian Americans. It was a very white, middle-class suburban high school. No one, I think, really understood what Korea was. It was like, “Oh, that’s where the war was.” And everyone would ask me, “Are you Chinese or Japanese?” And I’m not. I’m Korean. So it was a very alienating experience.

How did being treated that way impact your identity?

You know, I was very quiet. And it turned out almost all of my friends from high school were gay. They couldn’t be out because that wasn’t really a concept at the time in the early ’80s. We were the smart, misfit kids who had weird hair, and would sneak into Numbers in high school with our fake IDs. That was my tribe, and I’m still very close to all of them. They eventually came out in college or later. I’m glad I found them.

And I didn’t really even know what Asian American was until I moved to California because that wasn’t an identity back then in Texas. So I didn’t even feel Korean American or Asian American. I just felt different.

What about the Korean American community? How did you fit in or not?

Most of the Korean Americans didn’t live in our neighborhood. They lived in Spring Branch. My parents had this monthly Korean fellowship group. So when I was little, I was dragged around to these monthly groups and they were always really far away, like Meyerland, Sharpstown, Clear Lake. And I felt very different from all of the kids because I was really into movies and culture and, also for my age group, I was the only girl. Most of the Koreans I met were much more insular. All their friends were Korean because they lived in a small enclave, and I just didn’t have that experience. We didn’t go to a Korean American church, and that was how the community was centered. Also, my parents were very liberal, which was unusual for Koreans in Houston.

I found it moving when you wrote about how your father’s personality changed after learning the truth about his own father. He became talkative, like a different person than the quiet, stoic father you grew up with.

Totally. He became talkative and gregarious, and he became a hugger. I mean, my father is not a hugger! He still kind of lectured. That was his mode of communication. He was a professor, you know. But he became a much warmer, open person. And toward the end of his life, he was Mr. Friendly. My kids got to know that grandpa.

At the top of this conversation you said that you realized you were writing this book for your children, so they could have the history that you didn’t have. How did uncovering this history and writing the book affect you?

I feel like I’ve created a narrative for my family, and it definitely makes me feel more grounded and maybe more at home. I feel at home with my family. That’s the legacy that I want to leave my kids because I felt so not at home growing up. I had my immediate family, but we didn’t have family in the States. It was just the four of us. It felt very lonely. But my kids have gone to Korea several times. They’ve visited where my parents grew up. They visited their great-grandparents’ grave. So they’ve grown up with that knowledge. And I’ve just recently discovered there’s been psychological studies about how family stories and family histories are so essential for our identity building, especially for adolescents. That felt very redemptive to me. That’s what I was trying to do for them—to give them that sense of identity and grounding that I didn’t have.