The Spirit of the Montrose Is Alive(ish) on Lower Westheimer

Every month in Houstonia, James Glassman, a.k.a the Houstorian, sheds light on a piece of the city’s history.

To say that Westheimer Road is struggling with an identity crisis would be an understatement. The storied street is a colorful buffet of all that is Houston, and it’s easy to make a case that it is, in fact, Houston’s most famous street, all 18-plus miles of it. From its origins in Midtown to its unceremonious conclusion at the earthen levy of Addicks Reservoir, Westheimer showcases every aspect of Houston—high, low, chic, shabby, foreign, funky. You can find it all there. But the Westheimer that holds the most secrets of Houston’s history is Lower Westheimer, from Elgin to Shepherd, where today upscale is slowly replacing rundown, where decadence is replacing decrepitude.

The street’s host, the historic and artsy Montrose neighborhood, is a confederation of small residential, early-twentieth-century subdivisions. The artsy vibe remains due to its proximity to the world-renowned Menil Collection and Rothko Chapel, and the constant influx of college students from the University of St. Thomas, the ones who live in ramshackle garage apartments and sleep on futons. Literary stars like Larry McMurtry, Phillip Lopate, Al Reinert, and recently Bryan Washington helped introduce the world to the Montrose.

The Westheimer we know today is a patchwork of previously existing roads, from the extension of Elgin Street in Midtown that merged with the residential Hathaway Avenue, which intersected with the then-termination of Montrose Boulevard. German immigrant and ambitious merchant Michael Westheimer built a private road that led to his version of a plantation, where Lamar High School and St. John’s are today, at the southern border of River Oaks. Ultimately, the namesake road connected Houston to Fulshear, Sealy, and Columbus, and remains his biggest legacy.

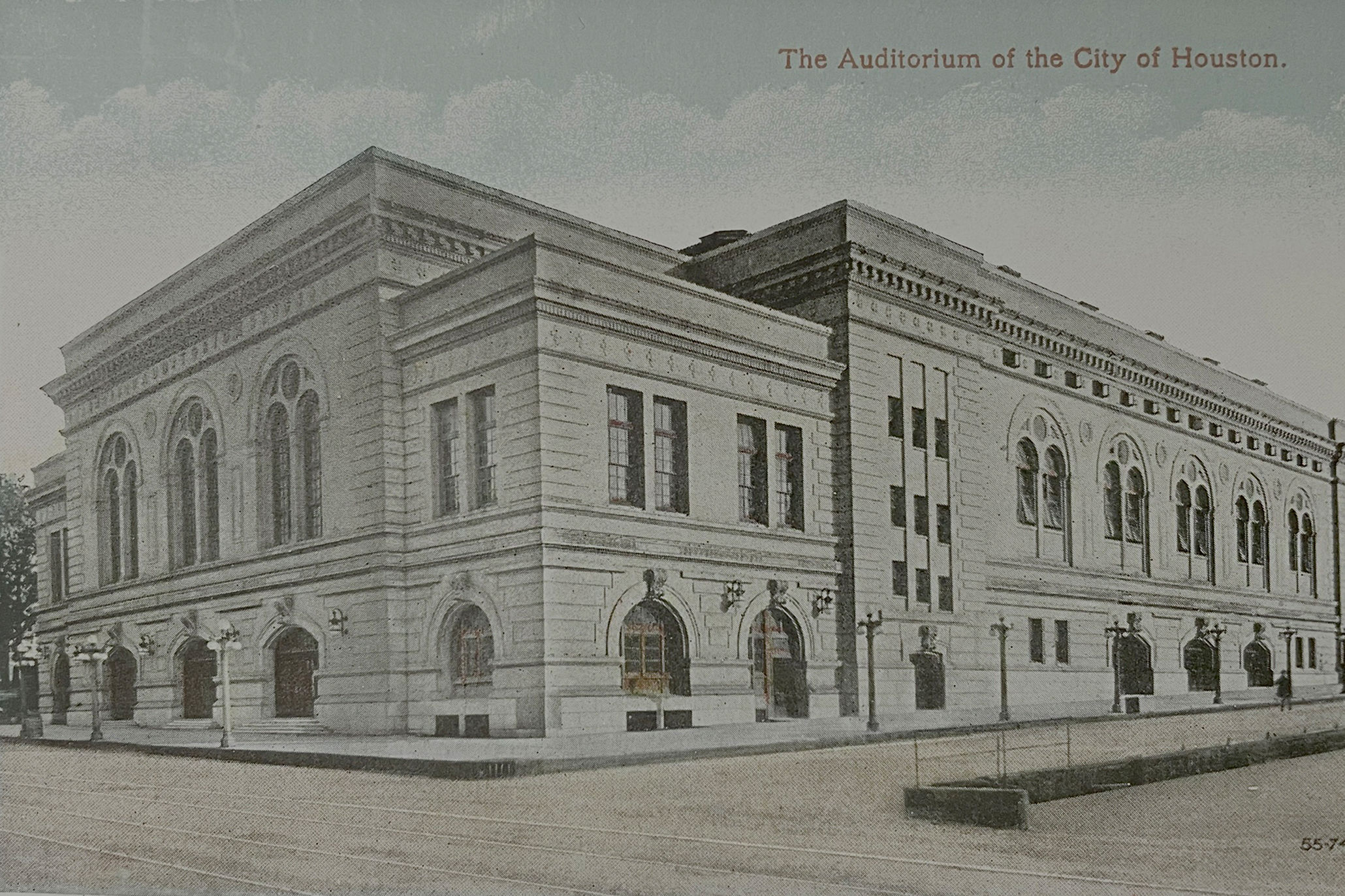

Image: COURTESY JAMES GLASSMAN

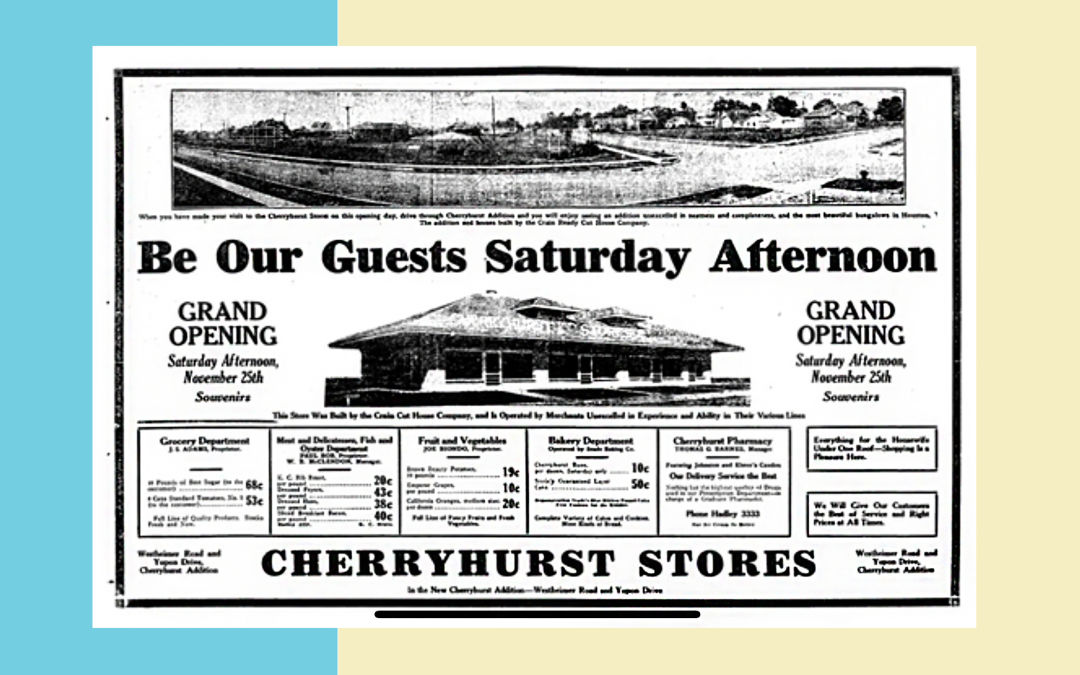

Paved Westheimer would absorb Hathaway and connect to Elgin. Zigging at the southern boundary of the Cherryhurst subdivision, Westheimer straightened out on a western route to the sprawl horizon. As the road became a major path into downtown, the homes evolved. Many of the homeowners moved on, and left behind the original structures for someone else to reuse. Small ethnic restaurants, wine bars, health food shops, and as the neighborhood aged, gay Houstonians found a growing community, and movement, there.

Even today, as it has been for decades now, the best way to enjoy Lower Westheimer is to ditch your car and simply wander. Where else in Houston can you stroll and find retail shops, dining, drinking, and as soon as the Tower Theatre reopens, a live show? Say what you will about gentrification, but Lower Westheimer still has the largest concentration and variety of nightlife in Houston. And plenty of tattoo parlors, junk and secondhand clothing stores, too.

Image: Todd Urban

Yes, the sidewalks, such as they are, suffer from a constant battle for supremacy with randomly parked cars or the aggressive roots of our storied live oaks. Currently, the City of Houston is making a good start at improving sidewalks along the historic street. While they’re at it, can they relocate the utility poles smack dab in the otherwise accessible path? It worked for Upper Kirby. OK, maybe the Upper Kirby treatment is too much infrastructural surgery.

In 2023, Radom Capital scored big with its Montrose Collective, which built on the neighborhood’s existing density and pedestrian scale. The imaginative developer is embracing Houston history with a current renovation of the 1936 Tower Theatre, easily the most significant landmark still standing on Westheimer. Depending on your age, you might remember it as a movie theater, cabaret, video store, or restaurant.

Image: Courtesy Library of Congress

Other notable historic buildings include the original Arts & Crafts–style Cherryhurst Stores at Yupon Street (current home to Catbirds); Hugo’s in a modest 1925 brick building—designed by legendary Houston architect Joseph Finger as a drugstore and soda fountain, later Imperial Plumbing Supply; and Lanier Junior High, just as solemn as the day it opened in 1926. Southland Hardware has been serving the Montrose from its current location at Morse Street since the 1950s, although the building itself could hardly be called significant. At this point, the only thing holding it up is the paint, of which they still sell plenty.

The 1924, one-story brick Fire Station Number 16 at 1413 Westheimer is still standing, even though the fire trucks left in 1979. Behind Lanier, a former gas station (circa 1930) on the corner of Westheimer and Hazard was bundled with two adjacent buildings in a 1996 renovation into the Winlow Westheimer Center, and designated a Protected Landmark in 2023. Fortunately, the stately house at 411 Westheimer is still with us as AvantGarden. The former home gives contemporary Houstonians evidence of the original residential nature of Westheimer Road (still named Hathaway). Many still remember its stint as The Mausoleum in 1996, or as Helio’s.

Image: Todd Urban

In the 1980s, Lower Westheimer became a perfect storm of unregulated car culture and cheap drugs, mingling with aging hippies and ascending gay culture. It was a weekend destination for teens from all over town looking for whatever, and a slow-moving, bumper-to-bumper parade in both directions, with the legal drinking age at 18.

By the 1990s, the cops and politicians ended the traffic snarls, but the party atmosphere remained, though moved indoors. My friends and I were neither punks nor goths, nevertheless we loved to scoff at suburban youth on their safari into the Montrose, seeking anything “alternative.” That word became a brand unto itself, then mostly lost its original meaning, but was quickly reborn in chain retailers that we dubbed as “mall-ternative.” Meanwhile, the punks were likely sneering at us. Runaways, hustlers, and drug dealers mingled with those artsy HSPVA kids at Emo’s, Lola’s, Numbers. It got scarier the farther you ventured down streets away from the bright lights of Westheimer. If you were looking for trouble, you need not wander too far.

Grown-ups had their joints too, like Ruggles, and, before everyone else had a Sunday Funday, La Strada with its bellinis and bottomless mimosas, occasionally leading to topless mimosas. El Tiempo now occupies the former party spot on Westheimer at Taft. Dress code is fully enforced.

Image: Todd Urban

Across the street from the Tower Theatre was the strip club Boobie Rock, with its windowless, futuristic facade announcing that Lower Westheimer was as close to Bourbon Street as you could get in Houston. You might remember its later incarnation as Chances, or more recently as Underbelly or Georgia James. The current velvet rope in front signals something upscale is being perpetrated within.

While the gay crowd has become more diffused in recent years, a few bars remain to the north of Lower Westheimer, on Fairview (Mantrose, anyone?). Long gone are Mary’s Lounge and the celebratory Gay Pride Parade. After more than 40 years, EJ’s, closer to Dunlavy, became La Grange in 2015, now the très fancy Melrose.

The early years of the 1990s saw the birth of two instant landmarks for Lower Westheimer: Cafe Brasil and Empire Cafe. Prior to these two, coffee culture in Houston was limited to Cuban restaurants, Greek diners, and IHOPs, catering mostly to Baby Boomer Houstonians after a night of bridge, or med students cramming in a quiet third space. The closest Montrosians had was Mai’s on Milam, which served (and still serves) killer Vietnamese coffee. Now we can drink coffee anywhere in Montrose, and share ideas, or just stare at our phones.

Many would argue, myself among them, that Poison Girl, the wonderfully unfancy bar near Dunlavy, looks like it’s always been there, due in large measure to its otherworldly back patio, where they, modestly, host a monthly poetry reading. Who says the Montrose isn’t artsy?

In a city where the unofficial motto is “What used to be there?” it can often be hard to rattle off a list of former landmarks. However, for Montrose, there persists a collective history where every current and former resident fondly laments their favorite long-gone store, venue, or event as vividly as a first love. This inner-city neighborhood remains preoccupied with its past in a way no other Houston neighborhood is. Despite its many changes, Montrose history lives, especially on Lower Westheimer.