Reflections on Sargent and Impressionism at the MFAH

John Singer Sargent, "Simplon Pass: Reading," c. 1911, opaque and translucent watercolor and wax resist with graphite underdrawing, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, The Hayden Collection—Charles Henry Hayden Fund.

Image: Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

The Age of Impressionism

Thru May 4

John Singer Sargent: The Watercolors

Thru May 26

The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston

1001 Bissonnet St.

713-639-7300

mfah.org

Without time there’s no desire, which artists know well. The trouble with time is that it’s fleeting and limits our desires, which is why so many works of art heroically but futilely resist its passage. Also fleeting? Exhibitions. As a number of shows wind down their time at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, I found myself in the midst of my own little remembrance of things past.

There’s something positively uncanny about seeing The Age of Impressionism: Great French Paintings from the Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute, which closes May 4th after an extended run. As a college student in western Massachusetts, freshly matriculated from a small upstate New York town with no major collection in reach, the Clark was the first museum I visited regularly. Nearly every weekend I’d lose myself in its halls.

Like the Menil Collection, the Clark was built around the tastes of one couple, Sterling and Francine Clark, who, in 1955, threw open the doors to a collection with particular strengths in French painting, especially impressionism, and Old Masters. It was the site of a number of “firsts” for me—my first Degas, my first Renoir, my first Pissarro, my first Monet—all up close and personal. These greats and more are available aplenty in The Age of Impressionism.

James Tissot, "Chrysanthemums," c. 1874–76,

oil on canvas, Sterling and Francine Clark

Art Institute, Williamstown, Massachusetts

But seeing a cast of familiar favorites in an unfamiliar setting prompted me to reflect less on the “greatest hits” of the exhibition than on what I hadn’t noticed before. Take James Jacques Joseph Tissot’s “Chrysanthemums,” an almost cinematic rendering of a quiet, perhaps private moment captured as a women crouches down to tend a solitary plant while a profusion of white, orange, and yellow petals explodes above her. She almost meets the viewer’s gaze.

Surprising too, after who knows how many water lilies, were Monet’s seascapes. “The Cliffs at Étretat” pits the gorgeous refractions of seawater against the dark sandy cliffs of a private cove, while “Seascape: Storm” brings to life the vicious green of roiling seas on which a tender craft wends its way.

Utterly arresting and unremembered by me were the works of Italian-born but French-residing Giovanni Boldini. In “Crossing the Street” a woman carrying a bouquet of bold flowers hikes up her gorgeously textured green dress as she crosses rough cobblestones. Behind her, city life goes on, indifferent to this captured moment of momentary discomfort. It appears to be the same person captured in “Young Woman Crocheting,” whiling the time away in a calm white room, as a young girl plays on a carpet checkered with color. In both paintings Boldini finds exuberance in bursts of color emerging from the gray, white, and brown palette of quotidian life.

In Massachusetts, I had many times admired Pissarro’s points of life and Degas’s dancers, but the painting I most vividly remembered was Jean-Léone Gérôme’s “The Snake Charmer.” A young boy, clad in only the twists and folds of a serpent, entertains a crowd seated against a gorgeous azure wall decorated with Arabic script. “The Snake Charmer” may be familiar to some as a cover image on an early edition of Edward Said’s Orientalism.

Seeing “The Snake Charmer” made me realize what was missing, for me, from this experience of the Clark on the road. I had always seen “The Snake Charmer” just before or just after John Singer Sargent’s masterful and meditative “Fumée D’Ambre Gris,” which features a gorgeous, white-clad woman holding a white veil like a dome over a censer emitting the smoke of the ambergris. Painted after he spent time in North Africa, Sargent was, like so many of the era, fascinated by the idea of the Arab world, yet more inclined to create romantic fantasies out of that fascination rather than accurate depictions.

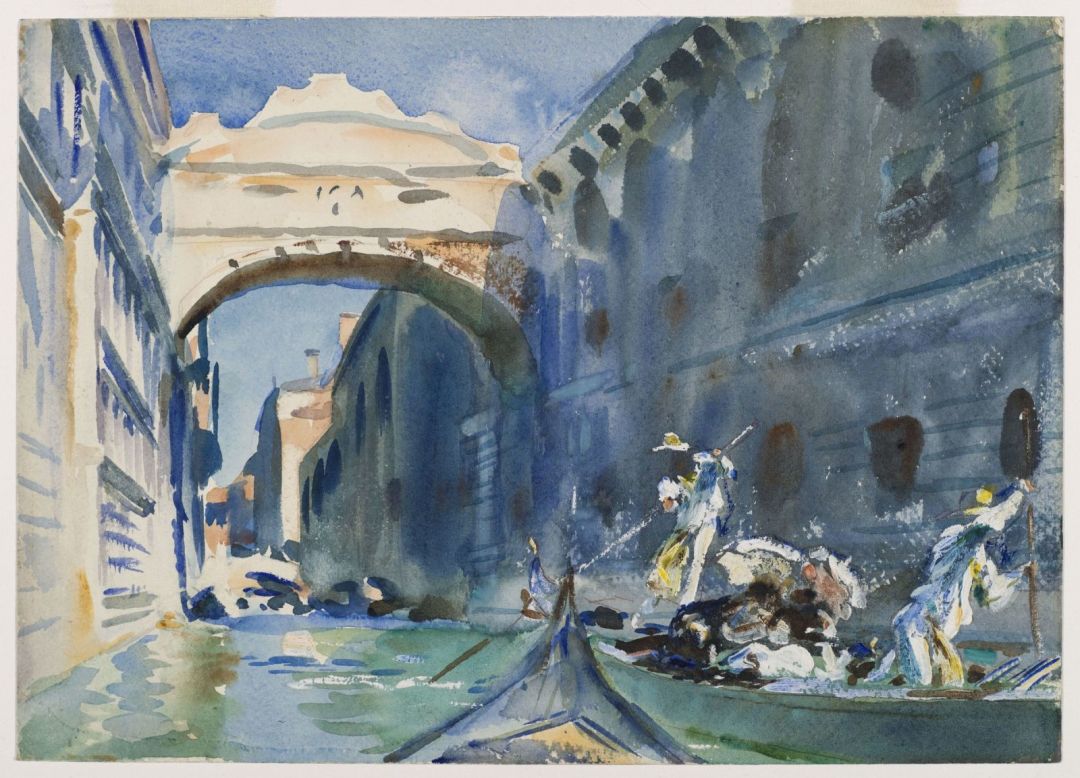

For all his affinities with the French, there’s no place for Sargent in The Age of Impressionism. Happily, I could wander downstairs to the impressive array of work in John Singer Sargent: The Watercolors, which runs through May 26th. Master of portraits and a wizard in oil, who knew Sargent was so accomplished in watercolors?

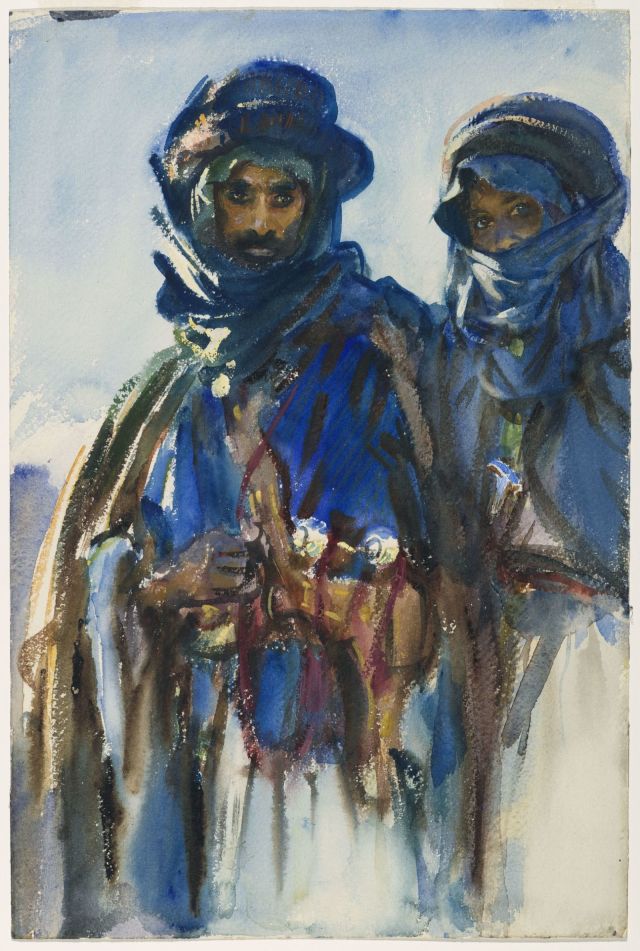

John Singer Sargent, "Bedouins,"

c. 1905–06, opaque and translucent watercolor,

Brooklyn Museum, Purchased by Special Subscription.

The story of the exhibition, as told in the beautiful exhibition catalogue, is a fascinating tale of art world entrepreneurialism. In the late 19th century, Sargent’s popularity incited the Brooklyn Museum and Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts to compete for the two collections of Sargent’s numerous watercolors, which he painted during his trips abroad, as if keeping a visual diary. The MFAH’s exhibition features a room containing a handful of locally owned Sargents, but it’s hard not to think that a certain great age of collection mostly passed our fair city by.

The exhibition is organized not by date but by topic—from “Arab Encounters” to “Watercraft” and more. A whole section, perhaps the most alluring, features figures in repose, stretched out or languidly curled on beds and couches. Something special happens to sleeping or relaxing figures, as in “Spanish Soldiers.” Stopping at the pilgrimage town of Santiago de Compostela, Sargent captured men recuperating in a bright courtyard, most seated. One leans stylishly against a wall, relaxed but confidently meeting the painter’s gaze. There’s something special about those Sargent subjects who meet his gaze, like the blue-clad “Bedouins,” which is shockingly vibrant and sharp for a watercolor.

It’ll be no surprise to Houstonians who saw the marvelous exhibition Sargent and the Sea at the MFAH a couple years ago that Sargent had an affinity for waves and watercraft. One expects something watery from watercolors, I suppose, but Sargent also achieves extraordinary precision in works like “White Ships,” where the rigging becomes a matter of mystery and light.

In his watercolors, Sargent observed attentively and rendered the world he saw with distinctive force and vibrancy. And yet the medium he used is famously fragile, which makes for one of the exhibition’s many intriguing tensions.

Would that the MFAH’s installation, with its funereal wall colors, better suited the work. Has maroon ever looked more lifeless? And while Sargent’s grandest portraits can easily command large galleries, these works are intimate; a more appropriately scaled setting might have done wonders. Something feels old-fashioned about the way this show is laid out. Happily, works as vital as those in The Age of Impressionism and John Singer Sargent: The Watercolors possess an immediacy not to be denied.