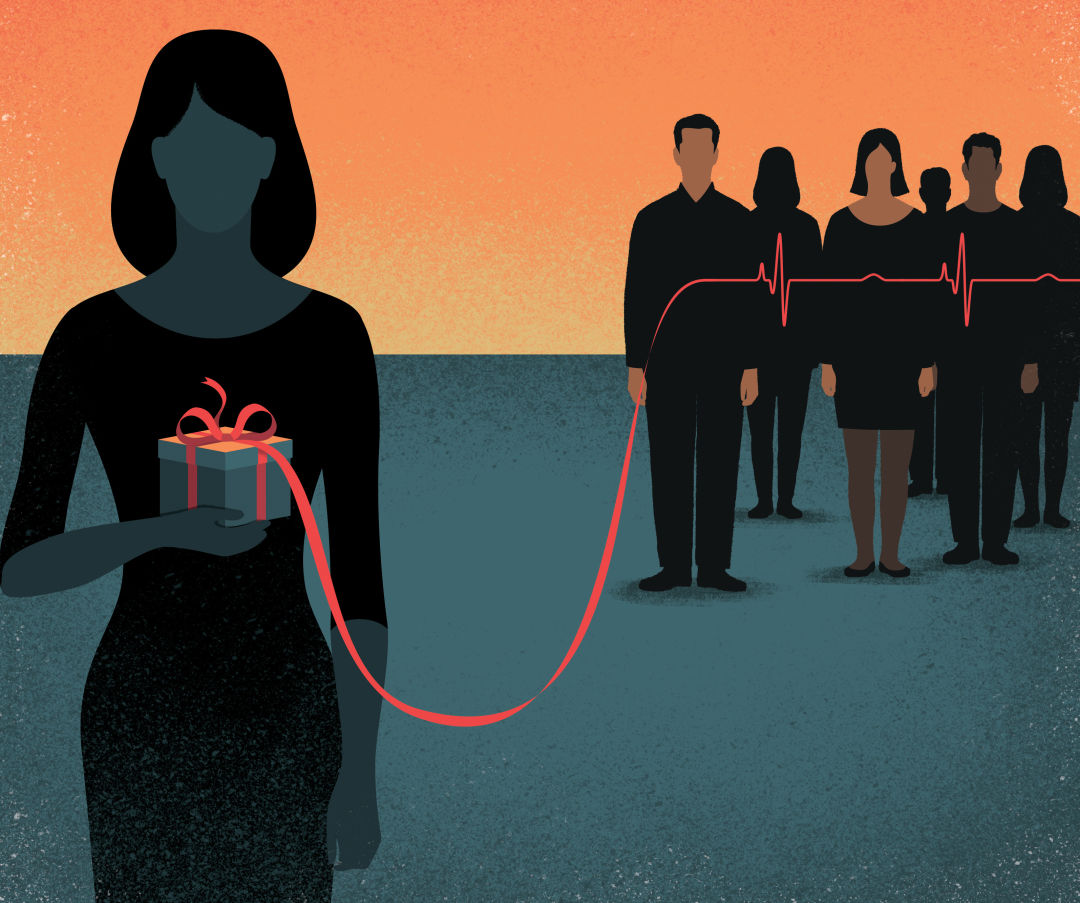

Out of Despair, the Gift of Life

Image: Davide Bonazzi / salzmanart

I’ve told my story before, but something was missing. It has taken me 12 years to figure it out. I’ve told the story of how my 44-year-old sister, Julie De Rossi, died a violent death at the hands of a drunk driver on US 59 South near Beechnut in the predawn hours of March 17, 2004.

I’ve recounted how the drunk driver was traveling an estimated 117 miles per hour, upon impact, his blood alcohol level three times the legal limit. I shared with a friend recently that through a search on the Texas Department of Criminal Justice website, I learned that in June 2009, shortly after serving his five-year sentence, he was convicted of another DWI, his third.

I’ve told friends about how I was out of town when the accident occurred, on a ski trip in Beaver Creek, Colorado with my husband and my 8-year-old son, Burke. With coffee brewing and bacon frying, we were groggily sorting through damp mittens and ski socks when the phone rang. It was my sister Julie’s son Aaron, then 25, who simply said, “You need to come home.” Julie was being kept on life support at Memorial Hermann Hospital in the Texas Medical Center until I could get there to say my goodbyes.

I’ve recalled how I frantically tried to find a flight home, not from Denver, a two-and-a-half-hour drive away, but from the nearby Eagle-Vail airport. After rushing to pack our bags, we had an excruciating hour to kill, so we went to the Hyatt Regency resort in Beaver Creek, to pass that time. Still unbelieving, I went to the hotel’s business center to use the internet, desperately searching for some evidence the accident had occurred. I found a video of the crash site, shot before dawn, posted by a Houston TV station. There, on the screen, was Julie’s Volvo sedan, crunched against the cement divider. I have recounted how it took me a while to realize what I was seeing; the trunk and back seat were gone.

My mother, Dorothy, tells the story of how she received a call from the hospital at about four in the morning. “You know it’s not good,” she’ll say. She called Max, her next-door neighbor, to drive her to the hospital. All she knew was that her daughter had been in an accident, and she needed to get there. With a distant look in her eyes, she’ll describe seeing her daughter, lifeless in the hospital bed, a single line of blood dripping out of the corner of her mouth. “She was gone,” my mom will say, lower lip quivering. “I will never get that image out of my head.”

In addition to being the victim of a drunk driver, my sister also became an organ and tissue donor. Two years after her death, we received a call from LifeGift, the organ procurement organization (OPO) here in Houston that coordinated my sister’s donations. The caller said a “high-profile sports figure” had been the recipient of one of my sister’s tissues, and a reporter from Bloomberg wanted to write about it. Shortly thereafter, we learned that it was Carson Palmer, then quarterback for the Cincinnati Bengals, at the time the highest-paid player in the NFL. Julie’s Achilles tendon had been used to repair Palmer’s knee, which had been blown out in a game against the Pittsburgh Steelers.

From that moment, our story evolved from one of a family’s grief and loss of a sister, daughter, mother and friend at the hands of a drunk driver, to a story about how a 44-year-old Houston woman’s Achilles tendon was used to repair the torn knee of a football star.

Not long after, I was asked to serve on the Donor Board of Trustees of the Musculoskeletal Transplant Foundation (MTF), the nation’s leading tissue bank. The board is comprised of representatives of OPOs from around the country, as well as representatives of the medical and funeral communities. I was to be the voice of the donor family, a huge responsibility. I worried that my views, based on my family’s experiences, might not be representative of others whose deceased loved ones had been donors.

After accepting the foundation’s invitation, I flew to New Jersey for an orientation, where I learned that my sister’s tissues, recovered in Houston by LifeGift, had been processed right there at MTF. I was astounded to learn that upward of 80 people’s lives were either saved or enriched by Julie’s donations, including, of course, Palmer’s.

When I would mention that figure to friends, they would always get that quizzical, dog-with-the-head-cocked look on their faces. I could just see them doing the math in their heads: One heart, plus one liver, plus two kidneys…it just didn’t add up. How could you get to 80? The answer is tissue. Tendons, muscles, corneas, skin. Whereas organs must be transplanted almost immediately, tissues are frozen and can be used much later. The physician who performed Palmer’s knee surgery (in Houston, coincidentally) on January 10, 2006, selected a tendon, Julie’s, that had been recovered nearly two years before.

I have recently come to realize that throughout all of this, one very critical piece of my family’s story has been missing. In the carefully orchestrated production of organ and tissue donation, twin spotlights are cast on donors and recipients, as it should be. But there, to the side of the stage, is a silent partner in the process, the OPO Family Care Specialist.

Representing LifeGift as such a specialist, Elena Mendoza was there at the hospital when Aaron and my mother arrived that morning in 2004, and she was still there, six hours later, when they left. She comforted them, helped them make sense of what was happening, and, at the appropriate time, gently asked if they would consider organ and tissue donation. My sister was brain-dead. (As my mother said, “She was gone.”) Elena suggested that although my sister’s life tragically had been cut short, through the donation, others could live. My mother and nephew knew that my sister, who had always been a very giving person, would have wanted that.

With the hindsight only the passing of time affords, I recently began to ponder these individuals who have the amazing courage—some might say audacity—to approach families, in their absolute darkest hour, about organ and tissue donation. I think Aaron nails it when he says, “it’s such a bizarrely rare breed of person” who can step into people’s nightmares, day in and day out, navigating their shock, horror and grief, to offer this silver lining.

From our experience, we know two things: When your loved one has just died suddenly, it’s hard to fathom death, much less donation. You are out of your mind with grief. But we also know that down the road, when your razor-sharp pain has been replaced with a dull ache, after the funeral is over and you’ve begun to try to reassemble your life, you will look back on that decision and feel grateful.

And so, I recently invited Elena to lunch. I wanted to meet the woman who has had such a marked impact on my own and so many others’ lives. Over sandwiches at Panera Bread on Holcombe Boulevard, I learned that Elena has always led a life of service. After graduating from Socorro High School in El Paso in 1985, she attended EMT classes at a local community college, at the same time working at a local sheet-metal factory to help support her family. Her mother, Maria Lydia Mendoza, worked for 25 years making 501 jeans at a Levi-Strauss factory on the U.S.-Mexico border.

After moving to Houston in 1987, Elena “rode the ambulances” as a paramedic supervisor for six years. She also worked as an assistant manager at a blood center before joining LifeGift, then known as Gulf Coast Independent Organ Procurement Organization, in January 1997. In January, she will celebrate her 20th anniversary with the organization. To date, she has worked with over 600 families like mine.

Her primary role, Elena says, is to be there to support families. Aaron wholeheartedly concurs, saying, “She was the first person there who didn’t look at us with pity. She was the one person there who we really wanted to talk to. Everyone else—the doctors and nurses—was clinical. Elena was sweet, passionate and caring.” But Elena says she’s also there for the doctors and nurses, who, despite their “clinical” demeanors, are feeling, caring human beings who hurt alongside their patients and their families.

Over lunch, I asked Elena how she musters the courage and energy, day after day, to face death and despair. Without missing a beat, she responded, “How can I not?” In the U.S. alone, there are currently over 120,000 men, women and children awaiting life-saving organs. Every day, an average 22 people die awaiting transplants. And when prospective donor families decline donation? “I feel I have failed them, failed to help them understand the opportunity before them,” she says.

In the heat of the moment, Elena is not always warmly received. “I have been called the Angel of Death; I’ve also been called Santa’s Helper,” she says. I call her amazing.