Houston Is Getting Its Own LBJ Statue

Image: Gensler

A lot of people were confused when word first got out that Charles Foster, a local immigration attorney, had decided to build a monument to Lyndon B. Johnson. Why Houston, of all places? After all, everyone knows Johnson’s story, how an ambitious boy from the Texas Hill Country grew up to become a towering figure in the House and Senate before becoming president after John F. Kennedy’s assassination.

But Houston never loomed large in his biography. Even Robert Caro, the man who has churned out thousands of words chronicling every aspect of Johnson’s life, devoted only eight pages to Johnson’s time here.

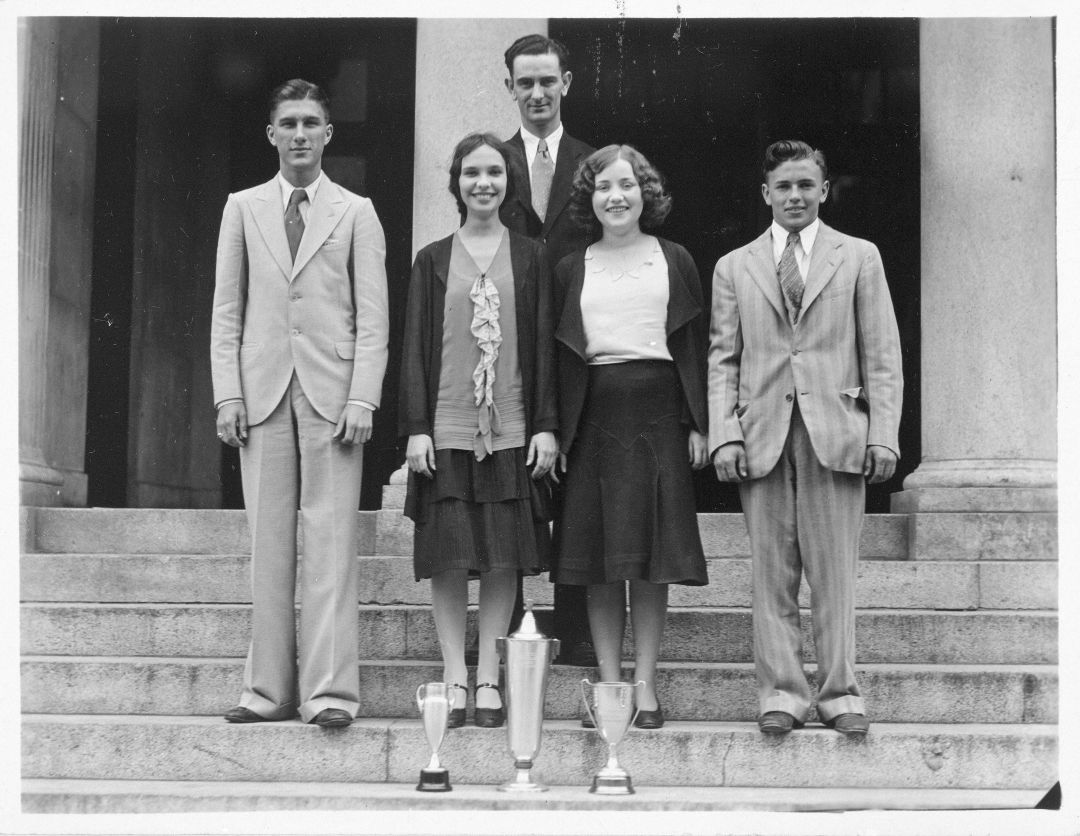

Nevertheless, Foster insists that Houston was important, that Johnson had “significant ties” to the city, even if it’s tough to identify much beyond the fact that Johnson arrived here in 1930, during the depths of the Great Depression, to take a job teaching speech and coaching the debate team at Sam Houston High School. The determined character who would soon emerge on the national political stage was already present: When he learned the debate team had never won a citywide championship, Johnson declared they’d take it with him at the helm, and the state tournament, too.

For 13 months Johnson lived in a two-story, white-frame home in Montrose, sharing a room with his uncle. He created demanding courses in which students gave speeches every day while he and their fellow classmates tried to pick apart their arguments, even heckling speakers to throw them off. Johnson himself acknowledged how harsh his methods were, but they proved effective: The team won the city championship for the first time and took second place at state.

And then, a few months into Johnson's second year at Sam Houston, newly elected Congressman Richard Kleberg, a Democrat from South Texas, asked him to join his staff. Johnson headed to Washington, D.C. in November 1931, launching his career in national politics. He never lived here again. Over the years he spoke fondly of Houston, even swinging through town just before Election Day in November 1964 to address Sam Houston High School. But that was about it.

None of this seems to faze Foster. The attorney loves presidential monuments—he was behind the creation of the George H.W. Bush statue unveiled in downtown’s Sesqui-centennial Park in 2004—and he believes public art is important. “We’re a great city,” Foster declares, “and we should have great public art that recognizes our ties to historic figures.”

Lyndon B. Johnson (top center), photographed in Houston in 1931 with his debate students at Sam Houston High School.

Image: Frank Wolfe/LBJ Library

This particular project seems to stem from Foster’s own personal admiration for LBJ. He’s been a huge fan for decades, ever since Johnson’s campaign for president, when he swung through Corpus Christi to address Foster’s junior college. Afterward, Foster went up and shook Johnson’s hand. It was a moment he’s never forgotten.

“I heard LBJ speak—he was a senator running for president in ’60—and at that point I was blown away by Johnson and followed his career,” Foster recalls. “Later, as a law student, I had the chance to work in the Department of Justice when Johnson was president and met him again, just like you meet anyone like that, ever so briefly.”

Today Foster is a prominent Houston attorney who has served as an immigration adviser to both President George W. Bush and President Barack Obama. He lives right across the fence-line from Johnson’s old boarding house in Montrose and even tried to buy the place when it went on the market back in 2011. Once Foster got the idea to create an LBJ memorial—a monument that would celebrate Johnson’s Texas-sized persona without dwelling on his complicated, checkered legacy—he couldn’t shake it.

Initially, neither of Johnson’s daughters was on board. Foster ended up directly reaching out to one of them, Luci Baines Johnson, to explain that what he was proposing was a positive representation of her father’s achievements. Given these assurances, she wrote a letter supporting the plan. In 2016 Foster put out a call for proposals, and a team led by architect CK Pang and artist Chas Fagan—the same duo responsible for Houston’s Bush statue—won the project.

That same year Houston Mayor Sylvester Turner gave Foster permission to use Little Tranquility Park, located on Bagby Street in the heart of downtown, as the site. The effort will take $1.5 million, but Foster already has raised more than half the funds, mostly through donations from philanthropists and civic-minded foundations.

Fagan says his bronze statue will capture the former president’s “dynamic personality.” The monument as a whole, the design team asserts, will highlight the natural beauty of the park and serve as an engaging, inviting space that’s both educational and beautiful. “This is not just a sculpture,” Pang says. “This is about the enrichment of the park.”

The plan is for the statue to be surrounded by curved pathways that will guide visitors through a series of inscriptions with a particular narrative of Johnson’s administration: his support for civil rights, his plans for the Great Society, and other positive moments. Vietnam will be mentioned, but everyone we spoke with avoided the question of exactly how the controversial war will be presented. “That’s a touchy subject,” Pang acknowledges.

Foster himself will have the final say on the placards that go with each portion of the memorial, and the text will reflect his own view of history. “When Johnson left the presidency, he left sort of in disgrace, at a low point, because of the Vietnam War,” says Foster, “and he never fully got the credit that I really thought he deserved.”