Houston’s Cultural Institutions Tackle Art Accessibility

The Art Car Parade is one of Houston's largest free events, showing off decked-out vehicles to hundreds of thousands of onlookers every April.

Image: Sarah Welch

With a dynamic crop of cultural institutions dedicated to performing and visual arts, Houston has become known as the art mecca of Texas, and one of the most artistic cities in the nation. The possibilities for viewing art on any given day are endless, from a stroll through the Menil Collection to an evening at Houston Grand Opera. However, this abundance does not always equate to accessibility, as many Houstonians are often excluded from participating in our rich arts scene for a variety of reasons.

Access to art can assume many forms. Ensuring an institution is inclusive to all visitors means serving people with disabilities, for example, or making sure languages other than English are represented in reading materials. It also means considering residents’ socioeconomic circumstances, particularly within different demographics, and providing opportunities for engaging with art that are affordable.

We spoke with two professionals in the art world about what institutions are doing to be more inclusive and accessible to all—and what needs to be improved.

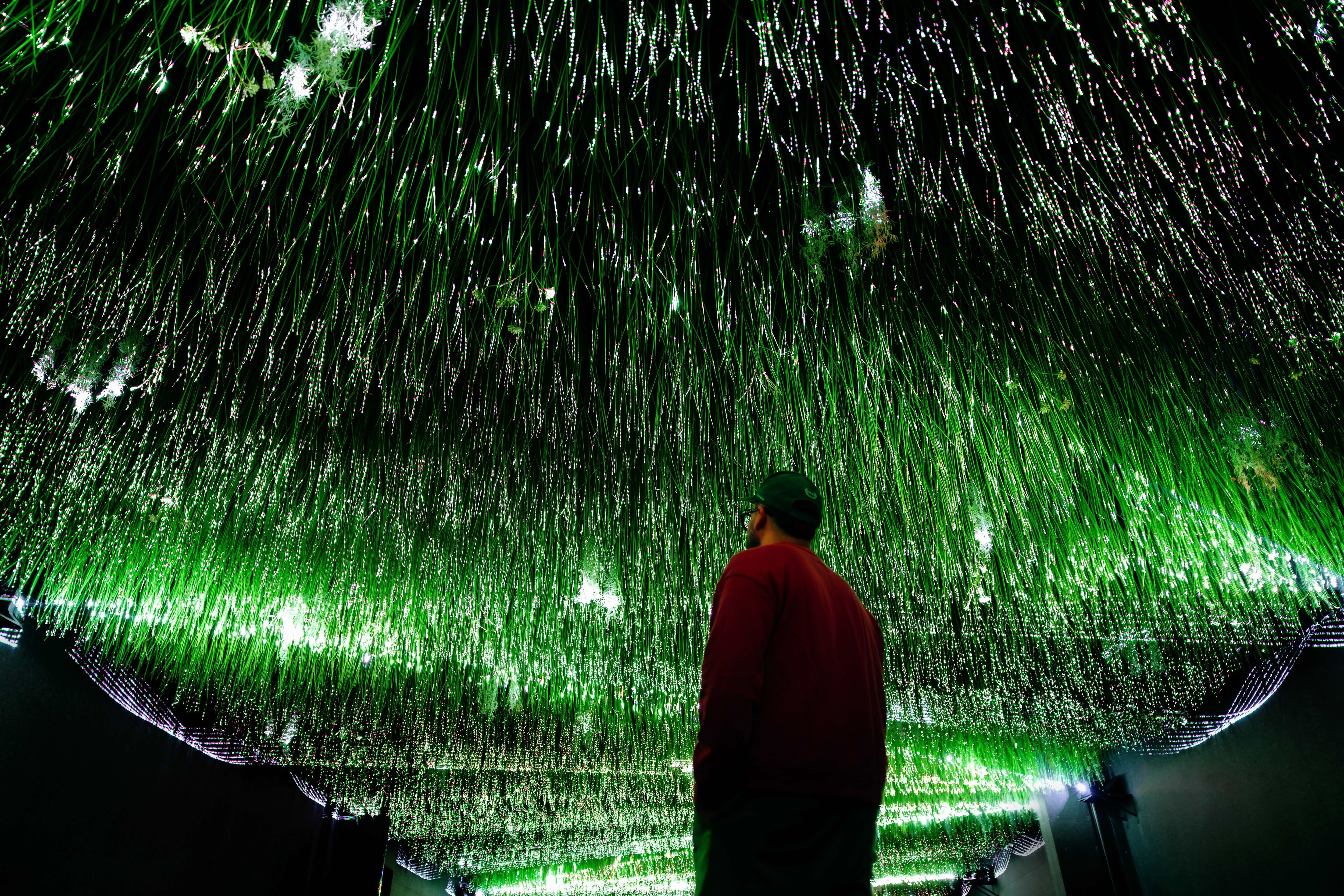

The Importance of Free Public Art

Public art is a vehicle through which a community’s values can be preserved, celebrated, and elevated. According to the nonprofit Americans for the Arts, it boosts civic pride, dialogue, and people’s appreciation for art. It can also be a crucial component of a city’s growth, including bringing economic benefits as artworks draw in visitors and local admirers alike.

Houston’s Art Car Parade is one of the largest free-to-the-public events in the city, drawing hundreds of thousands of curious spectators every year. Hosted by the Orange Show Center for Visionary Art, the parade allows the public to enjoy the magic of slabs (which originated in Houston), creative convertible contraptions, bejeweled roadsters, custom-crafted classics, and fur-covered, metal-modified, fire-breathing varieties—all for free. Kat Mims, office manager and artist liaison for the Orange Show, says that free art like the Art Car Parade promotes inclusion and is necessary for a person’s mental well-being.

“Art is for everyone, and it shouldn’t be an elitist thing where few people can access it,” says Mims, who’s been involved with the Orange Show since the ’80s. “The parade is a great example of that because we get a total of 250,000 people out there for free, and it’s very interactive and stimulating.”

Mims says another way the organization is promoting free and public art for all is with its Main Street Drag program, which is designed to “bring the parade to the people” by visiting schools, hospitals, nursing homes, and other locations where residents may not be able to attend the parade. “It just makes everyone happy to participate in some way,” Mims says. “The Texas Children’s Hospital brings the kids out on the balcony to see the cars.”

Several other Houston institutions and museums encourage the public to enjoy spaces year-round free of charge, such as the Menil Collection, the Art Car Museum (which is affiliated with the parade), Contemporary Arts Museum Houston (CAMH), the Houston Museum of African American Culture, the Lawndale Art Center, the Blaffer Art Museum, the Moody Center for the Arts, and Miller Outdoor Theatre. A newly created website, Houston Mural Map, launched in 2020 to help people find the city’s wealth of mural artwork. These organizations, along with the Orange Show, make it their mission to make art accessible for everyone.

“Not everyone can afford art, especially in a city this size,” Mims says. “I think that places that do charge admission should have at least one free day every week, or twice a month at least, so that their art is more accessible.”

Fortunately, many museums do. The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, the Buffalo Soldiers National Museum, the Children’s Museum, the Health Museum, Holocaust Museum Houston, and the Houston Museum of Natural Science all offer free admission on Thursdays during certain hours. The venues can become quite crowded during those times, though, and tickets on regular days cost up to $25.

Mims believes that once art is made accessible, more perspectives within the community tend to participate. “Our slogan is ‘celebrate the artist in everyone,’” Mims says. “With the Art Car Parade, we’re doing exactly that. We have 50 different schools, from elementary to high school, get involved and create cars every year. Teaching and celebrating the artist in everyone is the key to having a successful community.”

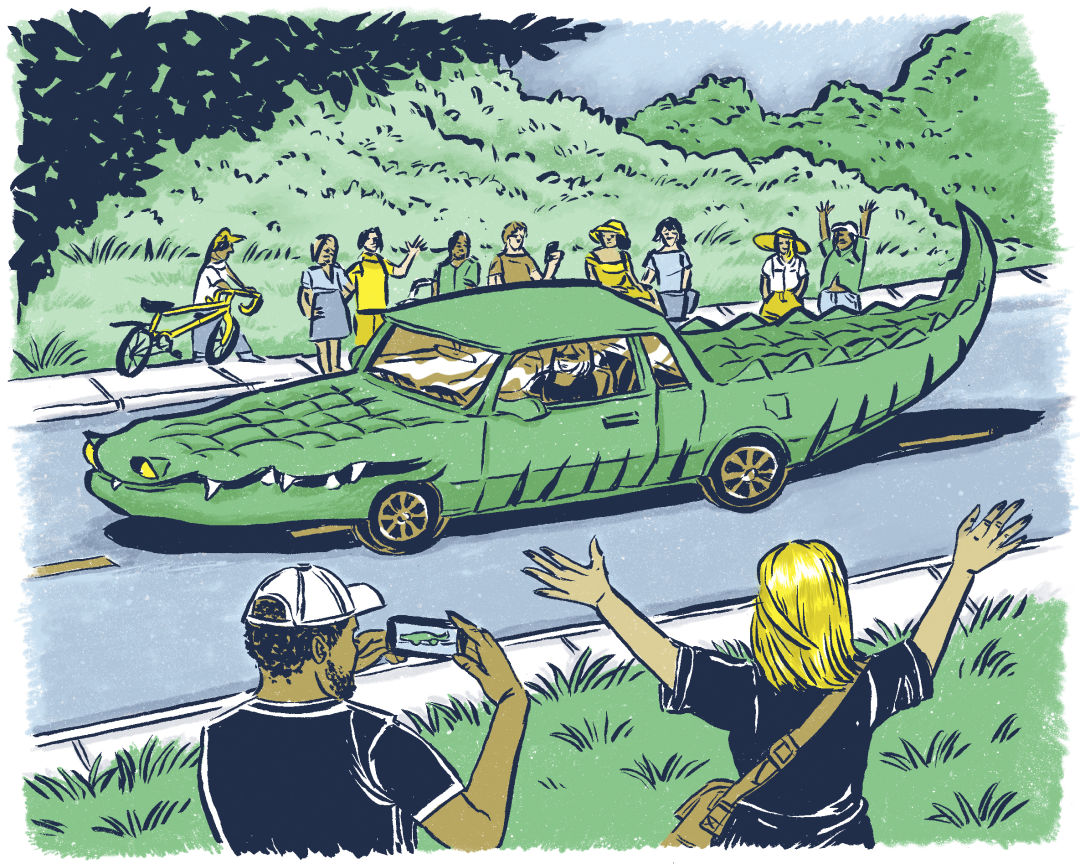

Contemporary Arts Museum Houston has started putting display text at lower heights.

Image: Sarah Welch

Welcoming People with Disabilities

For other underrepresented communities, like people with disabilities, organizations like CAMH have identified art accessibility as a priority. In the nearly eight years she’s been with the museum, director of learning and engagement Felice Cleveland says they’ve made cases lower so those at lower heights, such as a child or someone in a wheelchair, can properly view the items on display. The team also thinks about accessibility when putting text on a wall.

Seeing that culture focuses on creating dialogue, empathy, and human connections, Cleveland says accessibility is synonymous with social inclusion. “Everyone in a community is important, and we want people with disabilities to feel just as welcome and be part of that conversation, too,” she says. “What we try to do is be welcoming for as many people who are interested in coming here, and to fully recognize that it’s a work in progress. There’s a lot we still need to do, and I’m always thinking about different ways to make an impact and expand our audience.”

For the Art Car Parade, for instance, the Main Street Drag expands their audience in more ways than one. “When we go to the Lighthouse of Houston, the visually impaired are able to touch and feel the textures of some of the cars,” Mims says of the annual visit to a nonprofit that supports Houston’s visually impaired community.

Organizations like CAMH and the Orange Show are paving the way for others to follow suit. Museums, performing art centers, and even public parks across the city continue to roll out new and inclusive resources for visitors with disabilities, such as sensory maps, assistive listening devices, braille signage and “touch tours,” open captioning, and American Sign Language (ASL) interpretation. Main Street Theater, for one, holds special dates for ASL as well as sensory-friendly performances.

Translating the Arts

Creating meaningful inclusion encompasses a wide variety of considerations, and when engaging diverse audiences, a welcome sign is not enough. Accessibility programs and translation services are often viewed as separate resources, but Cleveland says they’re one in the same.

CAMH has remained committed to presenting everything within an exhibition in English and Spanish, giving more visitors the opportunity to read and learn more about the art, artist, and their process. The museum also offers tours in English, Spanish, and Russian, though the lineup can change depending on staffing; in the coming years, she hopes to expand these efforts to include more translated items digitally and in print.

“We’ve started translating everything from English to Spanish that’s on the walls, and I’m very proud of what we’ve accomplished,” Cleveland says. “This is my own personal philosophy, but I’ve always challenged our curators to have translations side by side, so we’re not saying one comes first or one is more important.”

Room for Improvement

While Spanish reading materials are quite commonplace in Houston, many institutions are still lacking translations in other languages that are widely spoken in the city, such as Vietnamese, Mandarin, Arabic, Hindi, and Urdu. As with every aspect of accessibility in the arts, there’s still plenty of work to be done.

Cleveland says providing the necessary resources is an ever-evolving learning process, and that there is no straightforward and approachable blueprint that all cultural institutions can follow. “We have some limitations, things we can and can’t control. For example, an exhibit with photography may not be inclusive to someone who is visually impaired, so the art itself can be an issue,” Cleveland says. “Also, we can always build lower cases and translate labels, but without funding, we can’t create a newer entrance. Funding is a big part of that.”

On the financial accessibility side, federal and state programs can sometimes fill in the gaps where funding within institutions is not sufficient. Families receiving Lone Star benefits can access discounted or free tickets to the Houston Zoo ($9), the Children’s Museum and the Museum of Fine Arts (both free), among others.

Government regulations and the Americans with Disabilities Act fill in to protect people with disabilities, but despite antidiscrimination laws that require public buildings to be physically accessible, there’s a gap between minimum compliance and the goal of engaging people with disabilities from the beginning through the architectural or curatorial planning in a museum. Cleveland suggests museums can do better by creating more opportunities for members of these communities to advise and design accessible programs, exhibitions, and spaces.

“People with disabilities should be the ones leading the conversation about their own interests and needs,” Cleveland says. “Working with people in specific communities to find out what they need and what works for them is very important. We can’t assume we know everything; I certainly am not an expert.”

An outsider’s perspective or opinion, however well-meaning, tends to overshadow the conversation and results in perpetuating stereotypes and misconceptions that only cause further barriers to access these spaces and programs. To avoid this, Cleveland thinks museums should organize advisory committees, focus groups, and community panels.

“If you want to include more sign language in a program or want to think about touch tours and sensory spaces for people who are neurodiverse, there are people who know way more about this than us that we can incorporate into the dialogue,” Cleveland says. “Wheelchair users can identify inaccessible routes within a gallery, or someone who is hard of hearing can suggest better visual descriptions. Be sure to talk to multiple people with disabilities in the process, and realize no one person can speak on behalf of everyone.”

Many cultural institutions could stand to lower their barriers to entry, but there’s still way more accessible art in Houston than people realize. By meeting the needs of visitors with developmental and physical disabilities, catering to people who speak another language, and making art free to those who can’t shell out money for their family to visit a museum, institutions across the city are sending the message that all are welcome.