Project Row Houses’ Biennials Change the Gallery Game

Artist Nic[o] Brierre Aziz completes his MFA with a concentration in sculpture from Yale University in May. The Haitian–New Orleanian will continue his already impressive career with a significant Houston arts achievement on his CV: winning Project Row Houses’ 2024 Southern Survey Biennial II. He received the $25,000 grand prize for his work on …as evil as bliss, a neon pink trap house styled like a New Orleans row house and filled with pantry staples, highlighting the commonalities and double standards between consumption and colonialism.

“Bill Rosenberg is the founder of Dunkin’ Donuts. Larry Hoover is one of the most renowned drug kingpins of all time…They both have used baking soda to create million-dollar empires in wealth. We look at one one way, we look at one the other way,” Aziz says. “The parallels between drug consumption and other forms of consumption, whether it be coffee and sugar and the oppressive histories that parallel both, is a question that has become a really large one within my work.”

…as evil as bliss will be on display until February 9, along with installations by Southern artists like Rabeeha Adnan, Violette Bule, Coralina Rodriguez Meyer, Amy Schissel, Martin Wannam, and Jamire Williams. Some of the artists will return to Project Row Houses on the final day for the de-installation process, and visitors are welcome to speak with them directly about their work. It’s a great opportunity to gain a first-person perspective on why artists who’ve lived and worked in the South deserve more national recognition than they often receive.

The first iteration, Southern Survey Biennial I, launched in 2022, when Project Row Houses executive director and art director Danielle Burns Wilson soaked up input from artists during the COVID-19 pandemic regarding how to best support them. Many felt compelled to uproot their lives in the South and head to New York or Los Angeles, hoping to expand their careers. Moving to hot spots can often be prohibitively expensive for young creatives, however. Wilson and the Project Row Houses team conceived of a biennial with a $5,000 stipend provided to every participating artist and a $25,000 grand prize to address concerns about the geographical opportunity gaps.

“Why should we feel like we need to leave what we love and know for the coast? It’s an ongoing narrative within art spaces. I think it’s time to think about it differently,” Wilson says.

Guest judges were also brought in from elsewhere around the United States to help give participating artists more exposure beyond the South. For 2024’s biennial, Project Row Houses selected Dr. Kimberli Gant, curator of modern and contemporary art at the Brooklyn Museum. She lived in Austin while working on her doctorate at University of Texas, so she already had some familiarity with Project Row Houses.

“I’m from the Midwest, from Chicago, very proud of that. Having lived on the West Coast, having lived on the East Coast, in the South, in Texas, in Virginia. I know that there are incredible artists beyond where a lot of the galleries are,” Gant says. “Any opportunity I get to work with artists that are from other places, I get very excited.”

She mentions that participating in events like Southern Survey Biennial II also benefits curators such as herself. Limiting her view only to New York artists homogenizes what should be an industry bursting with perspective and innovation. Project Row Houses was eager to facilitate more connections.

“I thought that it would be great to have someone with a platform like hers at the Brooklyn Museum to see some of these artists that she’d never known,” Wilson says. “Through the application process, there were so many talented artists that unfortunately weren’t selected just because of the amount of space that we had. But now she has an awareness of them, right?”

To land a chance to show their work in the biennials, artists must first submit a proposal to Project Row Houses. For the second event, about 100 vied for the seven available spots. The guest judge selects the finalists, then the Project Row Houses team collaborates with them to translate concepts into a full installation.

“I was running around picking up supplies…all sorts of stuff that they might need before and then during the week of,” says Cydney Pickens, curator and programming manager at Project Row Houses. “I stayed a lot of late nights, helping to install the work or coordinating with the contractors, helping to do any kind of painting, helping to put up our labels.”

Both Southern Survey Biennial I and II came into being to meet the needs of creators, but local art buffs benefit, too. Pickens points out that it’s also expensive to travel to New York and LA to see major gallery shows. Living in or visiting Houston allows for a comparatively affordable way to soak up the same world-class work you’d find in other big art cities.

“Being able to give away a $25,000 award really puts us on a big platform,” Pickens says. “A lot of people aren’t able to give that kind of money to a single artist or a single project, so that definitely is an attractive offer.”

For artist Rabeeha Adnan, participating in the 2024 biennial brought them back to an art space they consider invigorating. Now living in Brooklyn, they moved to Richmond in 2022 to attend graduate school at Virginia Commonwealth University after spending their life up until then in Lahore, Pakistan. They first visited Houston and Project Row Houses in 2023 while working on their MFA.

“The space was just very beautiful. It was very alternative. It was unconventional. And I think that a lot of galleries or museums you go to, you’re kind of used to seeing like a white cube in a very conventional way,” Adnan says. “But the idea of a shotgun house being appropriated for art, and thinking of social sculpture, just made a lot of sense.”

Their piece, Purring Table, takes full advantage of the homey setting. Visitors are invited to sit cross-legged around the eight-foot-wide furniture piece, the only work in the space. A hum is heard at close proximity. When one places their ear against the table, the purring clears into Arabic dialogue, spoken by a colleague of theirs. Adnan doesn’t speak the language, but they can read it and recognizes the adhan (Muslim calls to prayer) that they grew up around.

“The idea behind the piece in itself is that you come together at a point, you perform a gesture to receive, you submit to it, and then you receive something in return,” Adnan says.

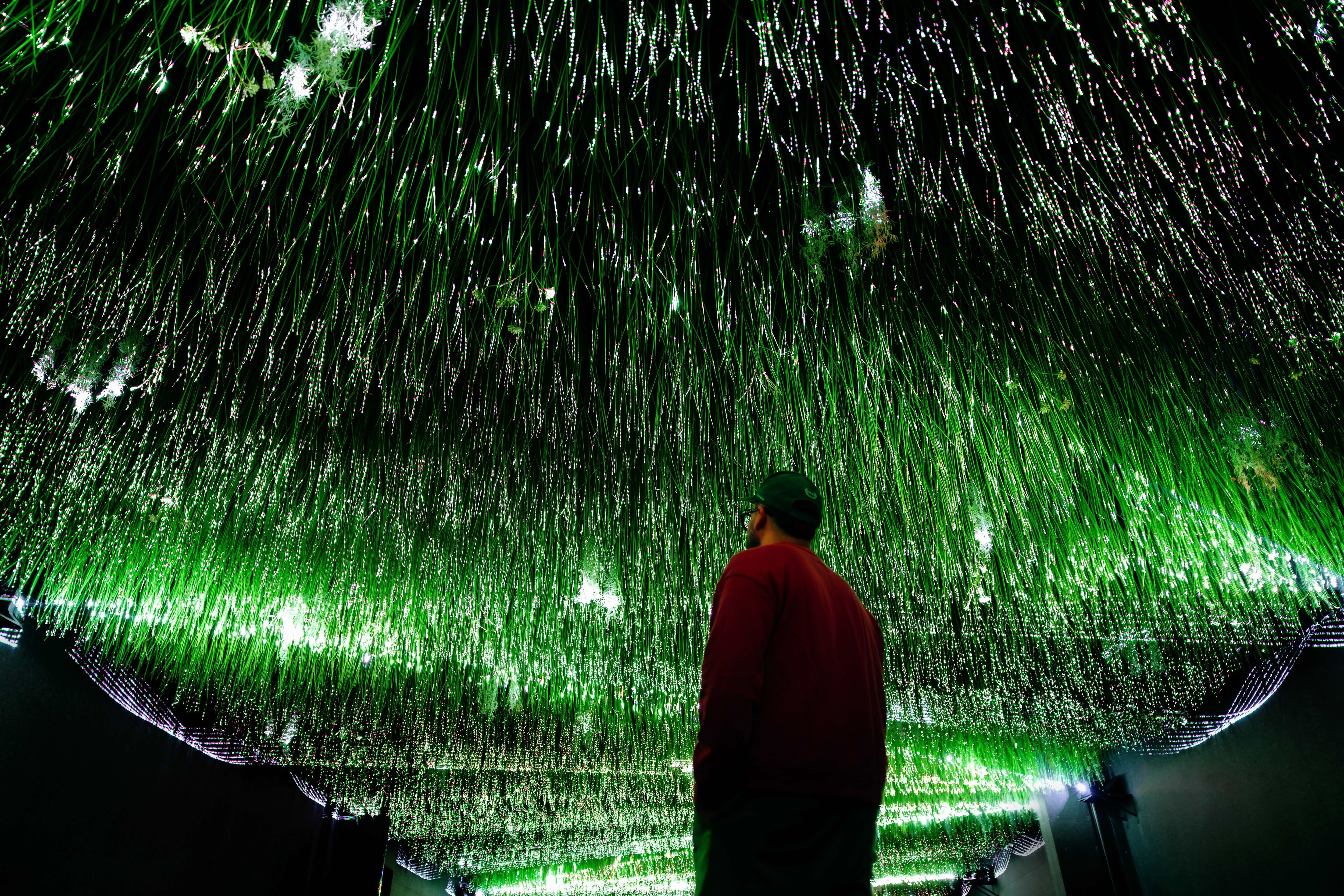

Next door to Adnan, Coralina Rodriguez Meyer’s Arco Kuychi Matriarch Monument pays homage to colonized peoples, maternity, unrecognized labor, resistance against colonialism, climate justice, and activist communities past and present. They grew up in the Everglades, and continue to live in Miami, where they pull from their Muisca Inca background to weave these themes into a multimedia narrative.

“One of the key statistics that emerged during my pregnancy: Florida had the highest rates of infant and maternal mortality in the United States, which has some of the highest rates in the developed world,” Rodriguez Meyer says. “I did not understand the site specificity of my heritage and of my background and my own upbringing until I contextualized it within those shocking statistics.”

Sculptures hold a reverent position in Arco Kuychi Matriarch Monument, molded directly from the bodies of pregnant people. Rodriguez Meyer refers to these as “mother molds” and “fertility effigies,” decorating them with visuals celebrating the birthing parents’ respective heritages.

“In our culture, there is much more association between the role you play and society and your identity, rather than your biology and your identity,” they say. “So the story that you tell about yourself vis-à-vis your community is the priority.”

They also found Houston’s arts community a refreshing and tight-knit network where fellow artists and art admins like Pickens were always eager to answer questions and provide any requested support, an environment where “very interdependent, very matriarchal legacies were still intact.”

Gant chose her seven finalists to participate in Southern Survey Biennial II because their work left her with the desire to engage “in dialogue with the artists.” Aziz’s pink house stood out to her the most, though she of course enjoyed every work she explored.

“I chose Nic[o] because I was just enamored with the final installation,” Gant says. “It was a multisensory experience that had several stories about Southern US culture—music, agriculture, class—and I had a visceral reaction to what he was able to accomplish.”

Now, Houston visitors have a chance to experience the same thought-provoking gut punch of an installation. Aziz was already thinking about the Haitian history of row houses and his own background when a friend sent him the Southern Survey Biennial II application. It was the perfect chance to activate concepts already under consideration.

“I just thought in terms of synergy, with the history of coffee and sugar commodities within colonialism and in the history of this country, and countries like France, and then Haitian history and connection of the porch. It just all came together in this, really, I think, just symbiotic way,” he says.

And when he was ultimately announced as the second-ever winner of the PRH Southern Survey Biennial prize—which won’t happen again until 2026—and received the $25,000 check, he says he really had to work to hold it together.

“My mom was the first person I hugged. And tears flowed in that moment,” Aziz says. “I just remember her saying, ‘You don’t have to cry right now. I’m going to cry right now.’ It was, yes, a really beautiful moment.”