The Literature of War

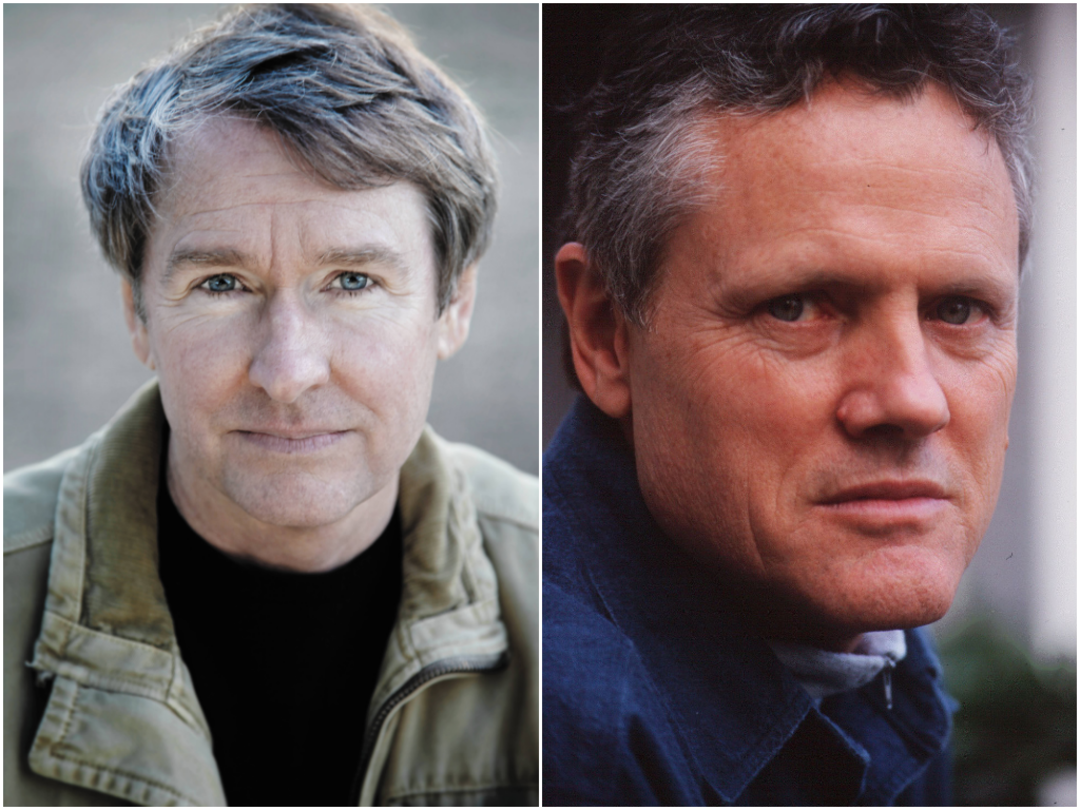

Ben Fountain and William Broyles

The Veteran Experience

Nov 5 at 6

Free and open to the public

Shell Auditorium, McNair Hall

Rice University

6100 Main St

business.rice.edu/veteran_experience

This afternoon at Rice University’s Jones Graduate School Business, six acclaimed authors who have written about war will speak at an event organized by Rice’s Veterans in Business Association. The authors include David Abrams (Fobbit), Lea Carpenter (Eleven Days), Bruce Jay Friedman (Violencia!), Karl Marlantes (Matterhorn), Ben Fountain (Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk), and William Broyles, the founding editor of Texas Monthly and the screenwriter of Apollo 13 and Jarhead. The event is free and open to the public. We sat down with William Broyles and Ben Fountain to discuss veterans’ issues, the combat experience, and the literature of wartime.

William Broyles

Why is it important to have events like this for returning veterans?

We’ve been at war for over 10 years, and it hasn’t touched many people in business schools or in the business community. It’s an all-recruit military, and there’s not much of an effect on most people. But there’s a strong and profound effect on people who serve, and we sent them, each and every one of us. It’s part of our responsibility as citizens, if we’re sending people off to war, as we’ve been doing since 2002, to know what we’re sending them to do. It’s also a way for us to expand as writers, to get to talk to people we don’t normally talk to. And the people we’re talking to get to listen to people they wouldn’t normally listen to.

How did your own military experience in Vietnam inform your writing?

Most people live on a narrow spectrum of life. The thing about war is that it pushes the spectrum out at both ends. You see amazing unselfishness and love on one side, and then you see these terrible things and scenes of death. There’s an intensity about it that brings out character, and that’s what writers write about. It’s one of the reasons that literature from the Iliad to today uses war as a subject. It also puts you in touch with people you wouldn’t ordinarily meet. In my days there was a draft, so the military was one of the few real democratic institutions in American life. In the military you’re thrown together with all kinds of people who you’d never have met otherwise. You notice people who would be invisible to you otherwise. It made me love America.

Do you think we lost something by getting rid of the draft? Is it easier to send people to war now?

The educated elite have generally not been exposed to this war. Without a draft, it’s easier to continue a war, because its effects are limited to a small group of very patriotic people. It’s much better for our country to have national service, because the effects of any decision to go to war are felt across a much wider section of society. That means that it better be done for the right reasons. We could never have had an 11-year war if we had the draft.

Ben Fountain

Why did you decide to get involved with this project?

You can imagine the reason why something like this would be helpful. So many of these young men and women come off four, five, six years in the military, and then it’s time to recalibrate their lives in a major way. I think the deeper and broader the community you have around you, the more feasible it is to do that in a way that’s going to work.

What can writers contribute to the conversation?

I think the value of writers is that they see thing for what they are, and they find the language to describe the way they see things. When a young man or woman is coming off an experience in the military, especially combat experience, they aren’t in the mood for bullshit. They’re trying to understand the experience they had. And that’s one thing I think serious writers can contribute.

Why did you decide to write about Iraq war veterans in your novel?

I had a lot of questions. I realized at a certain point that I didn’t understand my country, why we do the things we do, how and why we had gotten involved in these wars in Afghanistan and Iraq. And the only way I was going to have any hope of figuring it out was to write about it, with all the concentration and knowledge I could bring to bear, both through research and my own life experience.

Do you have any combat experience?

I do have some experience in life-threatening situations. I’ve been to Haiti 45 or 50 times, and at times Haiti is a combat zone. I never had a gun, so you couldn’t call it combat.

What would you say to people who would say, ‘Well, you can’t write about war unless you’ve been in it.”

I have the same question myself—it’s something that I wrestle with. It’s something I thought about all through the writing of the novel. Ultimately, I decided that this book was a powerful thing in me—I really need to try to write it. And maybe I can earn the right to write this book through immersing myself in that experience, and getting as close to it as I can. Writers are always writing about things that are beyond their lived experience. Anytime you get into matters of blood, of life and death, you can’t approach it lightly. It’s not a casual thing. You should only undertake it if you’re 100 percent all in, and dead serious.

Although your novel is very satirical at times, too.

Yes—being dead serious doesn’t preclude the use of humor. If instances of humor will serve the purpose of trying to get to the heart of the experience, then I consider that part of serious writing.

You talked to a lot of veterans as part of researching the book. What was that experience like?

The loyalty to the people they served with was, almost without exception, very powerful and very deep and profound. They were extremely astute politically. Maybe not in terms of what’s going on day to day in the political scene, but they had a very fine understanding of power, and the mechanisms of power, and how cynically those mechanisms can be abused by people in power. If you’re at the tip of the spear, you’re highly sensitized to what’s going on all up and down the length of that spear.