Bead-Bombing Montrose Blvd.

Image: EE Kachinski

360 Degrees Vanishing Kick-Off Party

July 11 from 6–8pm

Free

Art League Houston

1953 Montrose Blvd.

713-523-9530

artleaguehouston.org

When Houston fashion designer Selven O’Keef Jarmon was living in the Eastern Cape of South Africa, one of his favorite pastimes was to stroll through the bazaars looking for beaded items—necklaces, bracelets, even bowls—to buy from the sidewalk vendors. Over time, he began noticing that the vendors were disappearing. When he asked around, he learned that the vendors were giving up—no one seemed interested in buying their wares anymore. Saddened by the apparent demise of traditional beadworking, Jarmon resolved to do something to help the beaders, as well as expose the larger world to the intricate craft.

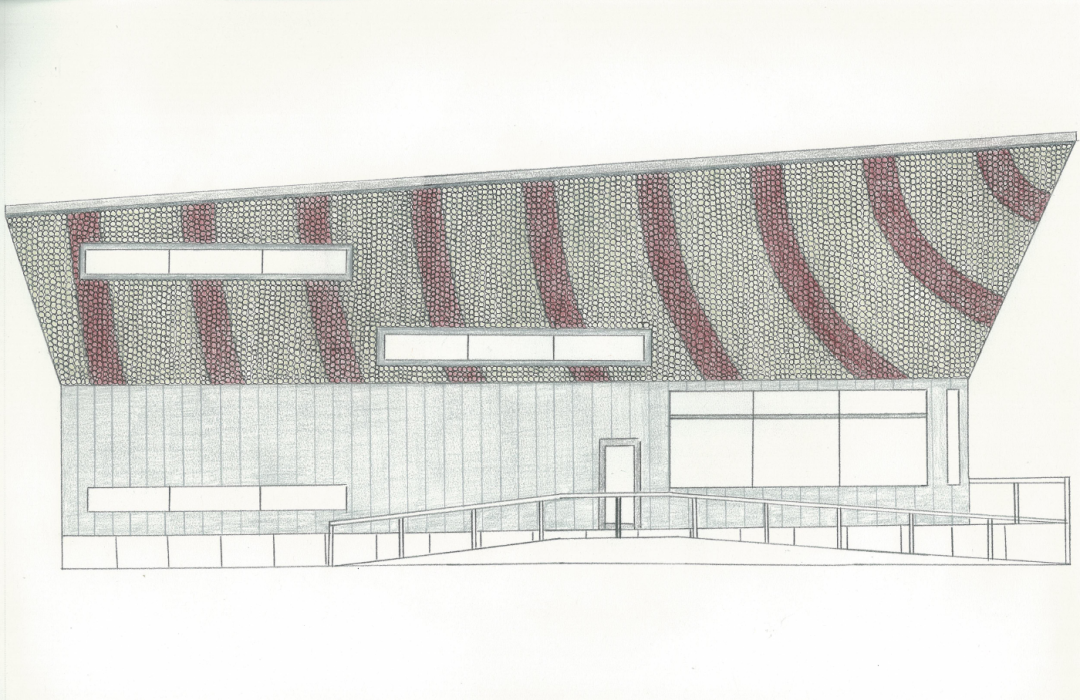

The result is “360 Degrees Vanishing,” a temporary public art installation by Jarmon that will be unveiled in October at the Art League Houston’s building (which is shared by the Inversion Coffee House) on Montrose Blvd. The piece consists of four large-scale beaded tapestries that will be cover the ALH’s four walls. “I wanted to do a monumental piece as a parody of the monumental idea that beading is vanishing from the landscape,” Jarmon told me.

Original working drawing for ALH installation

Image: Courtesy of Selven Jarmon

The tapestries will be made of around 350,000 acrylic beads and will be assembled over the next four months by 15 of the Eastern Cape’s most skilled beaders, who are being flown into Houston in groups of five. The beaders will live as artists-in-residence at the ALH campus while working eight-hour days at the ALH and Rice’s Bioscience Research Collaborative assembling the tapestries under Jarmon’s direction. The public will be able to observe part of the beading process. The first group of beaders arrives Friday, and will be welcomed with a kick-off party featuring a live performance by the South African dance troupe Ye Africa and food by local restaurants.

Although he moved back to Houston in 2010, Jarmon has vivid memories of watching the female beaders discuss their lives while working around common tables in South African households. “People bring their problems to the table—issues with their husbands, their children, political issues. And some things get resolved in the process of beading. Since we’ve opened this up to the public, we’re hoping that the same kind of sensibility kicks in, in a very organic way, that links two cultures and makes people feel like they’re part of this larger human tapestry.”

Bulelwa Bam, Director of the Eastern Cape Craft HUB

Image: Courtesy of Selven Jarmon

The South African beaders will assemble the tapestries out of 10-by-15-inch sections, which will be bolted onto steel cow panels—lightweight, gridded steel fences used to contain cattle—and mounted on the ALH’s exterior walls. The installation is scheduled to stay up for a full year, after which it will be disassembled and sold to art collectors.

Jarmon, who was born in Houston, first moved to South Africa in 2003, inspired by the 9/11 attacks. “I just felt disconnected from things going on in the world,” he said. “I wanted to be more conscious and more connected to the world in a more profound way than just creating clothing for wealthy clients. Up to that point, that’s what it was about.”

In South Africa, Jarmon designed the formal academic regalia for the new Walter Sisulu University in Mthatha and, in collaboration with the Nelson Mandela Institute, the uniforms for local schoolchildren. He participated in a reality television program that focused on improving the lives of five poor communities across the country. As part of that TV show, he founded the KWANDA Klothing Label, a collective of South African fashion graduates.

Since returning to the US, Jarmon’s work has been shown at the Contemporary Arts Museum, Houston, in group exhibitions at the Poissant Gallery and the Deborah Colton Gallery, and in the display windows at the downtown Dallas Neiman Marcus. But in the end, he said, it all comes back to fashion:

“Everything has been one big dress. I investigate construction in every garment I’ve done—that’s always been interesting to me. I’m using different materials, but in many ways the construction component is very relevant. I’m still a fashion designer at heart.”