Roger and Me

Life Itself

Open July 25

$11

Sundance Cinemas

510 Texas Ave

713-223-3456

sundancecinemas.com

Let me be clear from the outset: I cannot claim to have been as close to Roget Ebert as many of my colleagues who have waxed euphoric about Life Itself, director Steve James’s extraordinary new documentary about the life, work, love, and death of the great film critic, who died of cancer last year. We didn’t sport matching tattoos, we weren’t bowling buddies, and even before he stopped drinking, we never closed down any bars.

But I do feel entitled, and extremely proud, to call him a friend. On more than one occasion, he honored me by acknowledging our acquaintanceship, most notably when he wrote in 2009: “I first met my old friend Joe Leydon when he was the film critic of the Houston Post. When we see each other at the Toronto Film Festival, we are usually the oldest active critics in the room.” (Thanks again, Roger. I think.)

So when I say that Life Itself – which opens Friday in Houston at the Sundance Cinemas – gives me a welcome opportunity to share quality time with an old friend, well, that’s only because it does. And for that, I am immensely grateful. Roger and I were close enough to share – sometimes in private conversation, but more often via e-mail—our thoughts and, in my case, fears about mortality. During Roger’s first and seemingly victorious battles with cancer, I informed him that I had lit two candles for him at my neighborhood church as a prayer for his speedy recovery. “Thanks, Joe,” he replied. “But, you know, the candles work only if you actually pay for them.” To which I replied: “Hey, I paid $2. The last time a $2 bet paid off for me like that, I was at the racetrack.” He liked that.

Roger Ebert and Joe Leydon at the 2011 South By Southwest Film Festival

Image: Courtesy Joe Leydon

When I received my own cancer diagnosis a few years ago, I tried my best to put on a brave front for the very few people who were aware of my condition. Roger was virtually the only person in the world who knew just how scared I was, because I shared my terror with him, usually late at night, often after I had consumed a glass or four of Merlot. He was impossibly patient and unfailingly encouraging. Together, we actually found some humor in the situation. Midway through my radiation therapy, I joked: “I don’t yet glow in the dark.” As usual, Roger had the last word: “Glowing can be a convenience.”

Contrary to his recollections, Roger and I actually first met a couple years before I started working at the Post, back when I was a staffer for the Dallas Morning News and he was a guest presenter at the USA Film Festival. In 1980, he already was a superstar critic, thanks to his award-winning reviews for the Chicago Sun-Times and, more important, for Sneak Previews, the nationally syndicated PBS series that showcased him, Chicago Tribune film critic Gene Siskel, and their opposable thumbs. But Roger treated me as nothing less than an equal while we chatted —and, wonder of wonders, greeted me by name when we ran into each other again at the 1982 Toronto International Film Festival.

Throughout the decades, I have spoken with many colleagues who shared their own fond memories of Roger’s affability, approachability, and encouragement. At the same time, however, I have sporadically noted what can only be described as professional jealousy. Just a few days after Roger’s death, film historian Gerard Peary felt compelled to take several weaselly cheap shots at the man he mocked as “the full-of-himself Sun-Times guy.” Unfortunately, I suspect that Peary only openly acknowledged feelings that others silently harbor.

The irony is, Roger deserves credit—along with Gene—for elevating the profiles of US film critics who toil between the East and West coasts. Indeed, as Roger and I occasionally joked, he and his long-time frenemy likely inspired many newspaper editors to hire, or at least officially designate, their very own movie reviewers.

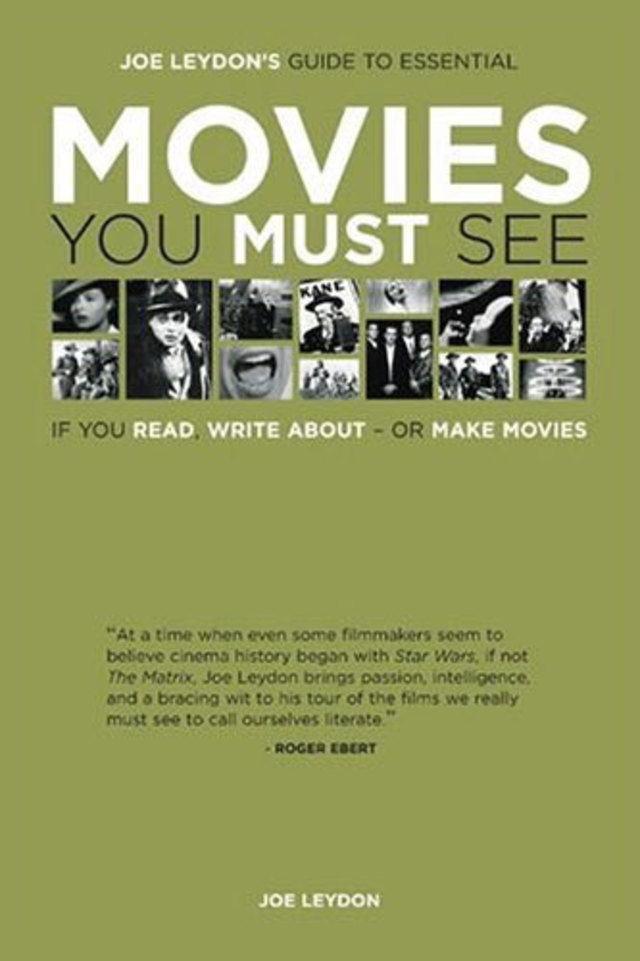

Cover of Joe Leydon's book Movies You Must See, with blurb by Roger Ebert

Image: Courtesy Joe Leydon

At the time Sneak Previews went into national syndication in 1977, relatively few newspapers in this country had a staffer specifically labeled “film critic.” If movies were reviewed at all within the paper’s pages, they usually were covered by someone also tasked with covering local music, dance, and live theater offerings. Indeed, when I got my first full-time newspaper gig in 1976, as entertainment editor for The Clarion Ledger in Jackson, Mississippi, I was told by my editor that film reviews never appeared in the paper, because management viewed such coverage as “free advertising” for movie theaters. (I am not 100 percent certain of this, but I think my review of All the President’s Men may have been the first film review to run in the 100-plus-year history of The Clarion Ledger.) I later discovered while speaking to colleagues throughout the country that this shortsighted attitude was, while not quite endemic, certainly not unique to Jackson in the ’70s.

Closer to home: the Post did not have a specifically designated film critic until the mid-1970s, when staffer Eric Gerber was elevated to the position, and immediately distinguished himself. Except that he wasn’t really, you know, the film critic. And neither was I, at first, when I landed the job after Eric took charge of the paper’s book review coverage in 1982. Evidently, someone in upper management disliked the term “film critic.” And so, until the Post changed ownership in 1983, my byline identified me as “Post Film Writer.”

More than two decades later, as financially challenged newspapers across America began to lay off film critics to cut costs, I e-mailed Roger: “Wouldn’t you agree that, as late as the early ’80s, and maybe later, there really weren’t that many full-time critics in the U.S.?” When I first got the Post job, I added, “Someone told me that more people were full-time pro baseball players than there were full-time film critics.” Roger’s pithy reply: “I am now advising aspiring movie critics to go into baseball.”

But here’s the thing: Just as the high-profile Watergate coverage by Bob Woodward, Carl Bernstein. and others made investigative reporting seem sexy in the 1970s, leading to a significant spike in enrollment at journalism schools, the success of Sneak Previews—and, later, At the Movies—had an incalculable impact on many of those “aspiring movie critics” and the editors who might hire them. To put it bluntly: Many film critics, whether they would like to admit it or not, got their jobs in the ’70s and ’80s at least partly because editors, cognizant of how large Roger and Gene were looming in pop-culture consciousness, figured film critics might, just might, be circulation-boosting commodities.

And more than a few of those film critics very clearly wrote while under the influence of their nationally syndicated role models.

Roger himself dutifully acknowledged the great Pauline Kael as someone who shaped his own sensibilities and career. Life Itself offers audio of his proclaiming: “Kael's influence shaped how critics look at movies—and how people read them.”) But Roger and Gene eclipsed Kael— and every other American film critic—in terms of reach and recognition very early in their TV heyday. Life Itself also includes an introduction by no less a tastemaker than Johnny Carson—“My next two guests are regarded as the most popular and most important film critics in the country!”—along with a clip of the classic Tonight Show moment when Ebert warily dissed the latest Chevy Chase movie, Three Amigos, while a not-entirely-amused Chase sat nearby on Carson’s set.

Not surprisingly, the ascendancy of Roger and Gene ruffled a few feathers and bruised some egos. As Jonathan Rosenbaum, a fellow Chicago critic, recalls on camera in Life Itself: “It became quite clear very often that the film companies cared a lot about Roger and Gene seeing [movies], but not so much about the rest of us.” More important, the TV stars occasionally caught heat from colleagues and other film aficionados for somehow “dumbing down” film criticism with their “Thumb’s Up/Thumb’s Down” approach to separating cinematic wheat from chaff. Again, Rosenbaum: “If you're talking about film criticism the serious way, consumer advice is not the same thing as criticism.”

Ebert’s counterpoint to his critics: “It would be fun to do an open-ended show with a bunch of people sitting around talking about movies. But we would have to do it for our own amusement, because nobody would play it on television.”

True enough, but more important was that Roger and Gene managed a delicate balance between show business and serious criticism in their televised give-and-take, providing the amusement of a practiced Mutt and Jeff show while stealthily spreading the good word about noteworthy artistic achievements between reports on standard Hollywood fare. It’s at least arguable that many moviegoers who normally avoided subtitled films the way Superman avoids Kryptonite sampled certain foreign-language imports primarily because they got the Roger-and-Gene Seal of Approval.

On television long after Gene’s death in 1999, and in print and online up until days before his own demise, Roger continued to champion movies he loved, and encourage many he simply liked, with undiminished passion and uncommon insight. His reviews remain easily accessible on RogerEbert.com, serving as an invaluable resource for anyone who loves, wants to make, and/or yearns to write about films.

As I noted shortly after Roger’s departure, the greatest thing about his reviews was—and still is—their bluntly spoken, openhearted directness. Just as François Truffaut used to proselytize for a cinema that spoke directly to audiences—“More personal than an individual and autobiographical novel, like a confession, or a diary”—Roger wrote reviews in the manner of someone addressing an acquaintance in a café, describing his passion (or lack of passion) for this or that film without pretense or self-censure, speaking from the heart without artifice or self-indulgence.

And while he might change his mind from time to time – note the borderline-hilarious disparity between his original 1967 review of The Graduate, and his 1999 reappraisal – the same passion seeps through both initial rave and revisionist critique.

His reviews abound with insights that come only after careful consideration, and his entertaining style is clearly fueled by nimble intelligence and a strong sense of film history. He was, in short, a great writer who wrote best about what he loved most. (Remember: he was the first—and for several years the only—film critic to win a Pulitzer Prize.) And even when cancer treatments denied him the ability to speak, he continued to write—prodigiously, obsessively—with a gleeful industriousness that could make his contemporaries (like me) look like just so many slackers.

Scarcely a week has gone by since Roger’s passing that I haven’t gone back to read or re-read one of his vintage reviews. And I still find myself thinking from time to time, “I wonder what Roger would have written about this one? Or that one?” I miss his reviews.

And, yes, I miss my friend.