Paul Auster Is Sorry His Book Is So Long

PAUL AUSTER IS A LITERARY LEGEND, with a bibliography spanning over 40 years. His latest novel 4 3 2 1 is a whopper: at nearly 900 pages, it’s his longest yet. The book follows four different versions of the same person, a boy named Archibald Isaac Ferguson, as he comes of age in the 20th century. As each Ferguson grows and changes, Auster plays with ideas of identity and personality as they head toward their ultimate fates. It’s no traditional bildungsroman, even if Auster himself is traditional in his habits; he doesn’t use email, doesn’t have a cell phone, and writes his books with pen, paper and typewriter.

On Monday, February 12, Auster will headline the fifth evening of Inprint’s 2017–2018 Margarett Root Brown Reading Series. Houstonia caught up with Auster to talk about his latest book—now out in paperback—ahead of his visit.

You’ve written so many books. When you think about 4 3 2 1 alongside your other work, what feels different about it for you?

The most essential difference between this book and every other book I’ve written is its size. It’s so big that I worry sometimes that readers might drop it on their foot and hurt themselves. I’m glad it’s in paperback now. Fewer broken toes.

Was it a challenge for you to write something that long, or was it something that felt natural for this story?

It had to be long because of the structure. In essence, it’s four novels—not one. Four intertwined stories, rotating in order, one after the other, each one about 200 pages long. But it does give the impression of enormous bulk. In the end, I feel it’s a single, unified book, one big story, told in several strands.

What was your writing process like for this book? You’re juggling four different narratives, but it’s four versions of the same person. How did you make that work? What did your day-to-day look like on this book?

The truth is that I didn’t have a plan. I improvised the book from the beginning, without a very clear idea of what I was going to do. I had the form: I knew there were going to be the four boys, and I knew I was going to tell it in a particular order. That was never in doubt. But exactly what was going to be in each chapter was more or less invented on the spot. I felt as if I were caught up in an enormous piece of music, and that I was dancing to that music. The essential thing was to keep listening to the music, to keep dancing to it. I understand that the book is an elephant. But I hope it’s a sprinting elephant.

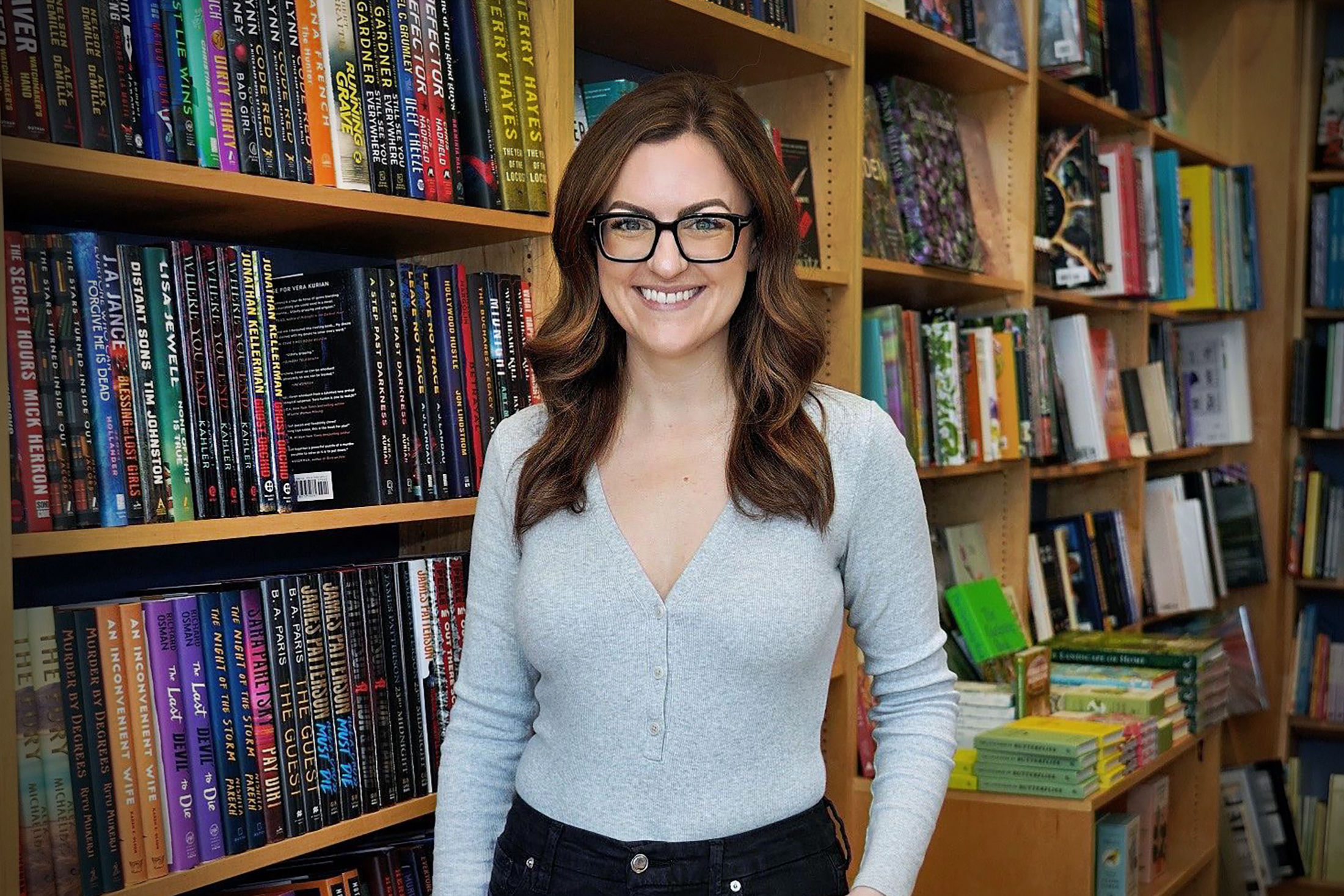

Paul Auster

Image: Maki Galimberti

I recently read Nathaniel Hawthorne’s Twenty Days with Julian & Little Bunny By Papa, which you wrote the introduction for.

It’s a wonderful book, isn’t it?

Yes! It’s one of the things I’ve enjoyed most that I’ve read this year. I liked how you reframe Hawthorne—people tend to think of him as this brooding, solitary figure because of his fiction, but his journals show us that he was also a devoted family man who loved his wife and children. Is there a side of you that your nonfiction reveals that people might not know about?

Oh, boy. It’s not for me to say. All they can do is read it and then draw their own conclusions. I can tell you one thing, though. Writing a novel is exhausting work, and at the end of the day both your mind and your body are pulverized. I’ve found that not worrying about the book after you’ve stopped is the best preparation for the next day’s work. You have to shut down your thoughts and let the unconscious take over.

I like that idea of stepping away and letting the unconscious take over. There’s a great essay by Zadie Smith called “That Crafty Feeling” where she gives her steps for writing, and one of them is “stepping away from the vehicle”—putting what you’re working on aside and letting your mind take over and wonder elsewhere.

I know Zadie, and she’s right. Often, a night’s sleep will solve a problem that you had the day before. You wake up, and you know the answer. You haven’t consciously looked for it, but it’s there, working its way through your brain so you can finally articulate what you need to say. But it can take some time. Writing fiction and poetry, it’s very mysterious where this stuff comes from. I think the real job of the writer is to be open: open to everything that’s flooding through you, not censoring your thoughts and staying relaxed. If you’re not relaxed, it’s not going to happen. As my wife Siri Hustvedt often says, art is like sex—if you don’t relax, you’re not going to enjoy it. And she’s right! (Laughs.) When people approach a work, they can feel anxious, intimidated, angry. They want to dislike what they’re going to read. And if they want to dislike it, chances are they will dislike it. But if you just take it easy and try to listen to what the writer’s doing and try to judge it on its own terms, you’ll have a better experience.

In the book, there are four different versions of Archie Ferguson. Assuming that you’re one version of Paul Auster, what do you think the other three versions of you are doing right now?

That’s a very good question, but I have no idea how to answer it. Of course, sometimes I think about the different paths my life could have taken. I think we all do this: there are certain key moments when you’ve come to a fork in the road—maybe without even understanding that you have—and you go one way or the other. If you’d taken a different path from the one you did, your life would be completely different.

For example: Siri. We met 37 years ago, and it was by complete chance. We were at a poetry reading together in New York at the 92nd Street Y. I went because I knew one of the readers, and I wanted to support that person. Siri happened to like that person’s work. At the time, she and I knew one person in common in the whole universe. Only one. And he happened to be a graduate student at Columbia, as she was then, and he introduced us. If I hadn’t met her, well, the last 37 years of my life would have been completely different. I wouldn’t have married her, and our daughter never would have been born—along with a thousand other things that never would have happened to me.

Strangely, I almost didn’t go to the reading that night. I was tired, I’d just come back from a trip. But at the last minute, I decided to go. And that’s how I met my wife. I often think about how things would have been different if I’d stayed home that evening. (Laughs.) That’s just one example of what we’re talking about—but it’s a big one, the biggest and best one of all.

Paul Auster, Inprint Margarett Root Brown Reading Series. Tickets $5. Alley Theatre, 615 Texas Ave. 713-521-2026. More info and tickets at inprinthouston.org.