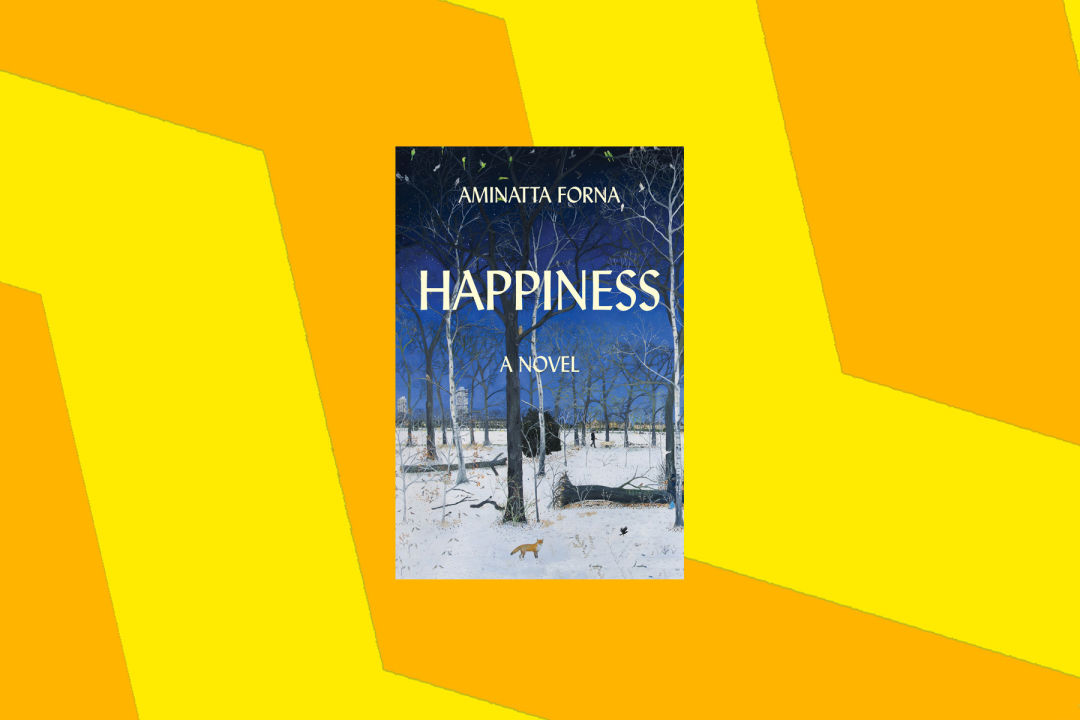

Aminatta Forna Talks Happiness, Immigration, and Why She Sometimes Pees Standing Up

Image: Courtesy Bloomsbury Books

For author Aminatta Forna, putting a new book out into the world is “unnerving, but it’s good.” Her newest novel, called Happiness, follows a Ghanaian psychiatrist named Attila, who studies trauma, and an American scientist named Jean, who studies foxes. As Attila and Jean’s paths serendipitously cross again and again, they become participants in a story much larger than just their own.

Forna will join author Samanta Schweblin next Monday for the sixth evening of Inprint’s Margarett Root Brown Reading Series. We caught up with Forna to talk about Happiness before she visits Houston.

I wanted to ask you about the title of the book. It’s simple, but so declarative, too. How and when did you know that Happiness was the right fit?

I had the first idea for the book in Massachusetts, where I was teaching at Williams College. I was only there for a semester, and I went back to Britain. I finished half the book, and then I had a job offer to come and teach at Georgetown. So I had to close off the book, put it away—which I’ve never had to do before—move [countries], my house, my kids, my husband, and pick up a new job. There was a six-month gap between those two periods. Both countries are going through sort of existential moments, both Britain and America. But there was something about moving to a country where “happiness” is a life goal. No other country in the world has happiness as a stated life goal. So moving to a country like that, while I was thinking about all of these things and how we really live together, that brought me to a new perspective in those closing chapters.

You give immigrants so many different and various voices and experiences in Happiness. Did current events affect how you saw or wrote those characters in any way?

I began the book well before Brexit, but there was one thing I was inspired by. I live in southeast London when I’m not living in America, and after the war in Sierra Leone during the '90s, Britain gave a lot of the refugees an open pass to come to Britain. And most of them settled in southeast London, around where I live. So, as someone whose father is Sierra Leonean and has spent time in the country, I suddenly found myself surrounded by people whose world I knew, and some of whom I quite literally knew—my mother’s hairdresser showed up! (Laughs.) So I was able to watch how this population was adjusting to life in Britain after enduring so much in Sierra Leone—such an astonishing level of brutality. They had come to London and were making their lives. And I was really struck by the level of resilience and determination and positivity there was around all that.

In the current moment, it’s very easy to strip people of the nuanced complexity that is the human experience—of the human character—and portray them in a one-dimensional way, as immigrants-slash-victims-slash-refugees. But they have complex lives, they have all the same dreams and aspirations that they had before and that everyone else has.

I loved your essay for The Guardian, “Don’t Judge a Book by its Author,” which was published in 2015. You’ve long been a champion for diverse voices in literature. Do you think there’s been any change or improvement over the past few years?

One point I’ll raise is the issue of appropriation. In “Don’t Judge a Book By Its Author,” I was talking about that before the word “appropriation” really started to be used. I am shocked and baffled by both extremes in this debate. It doesn’t seem to me to very complicated. (Laughs.) Fiction is a work of imagination: Without that, it’s over. If I had to write every character as someone just like me, there would be no novel. It’s a three-second thought process!

Aminatta Forna

Image: Jonathan Ring

However, all of that doesn’t mean—as at least one white writer has suggested—that your books can’t be critiqued. I mean, I spend a lot of time trying to figure out my characters. I go to their worlds, I do their jobs. When I wrote my first male character, I even practiced peeing standing up. (Laughs.) Which is not as great as it’s cracked up to be. It’s not that great! After it, I just thought, all that fuss, all that sense of superiority, and no one ever mentions splashback! (Laughs.) But I spend a lot of time thinking about what my responses would be if I had these choices as opposed to those choices. How would I navigate a situation if this was the set of choices for me? So I spend a lot of time trying to walk the walk of my characters and speaking to people in those worlds, talking to people about what it’s like to inhabit their body.

Where portrayals go really wrong is when a writer simply uses the material of other writers to create those characters. They’ll say, “I’m going to write a Native American character.” So they read books and watch films and use secondhand material to do their research—and then they’re in danger of repeating prejudices and perpetuating stereotypes. That’s where it goes wrong. There’s a great sensitivity about it on the part of some white writers, but, you know, we’re all under constraints. We’re all under constraints that we don’t wish to be under, but mostly there is unity on this subject, which is that it’s ridiculous. Fiction is an imaginative art. When people talk to me about appropriation and some young woman or man feels that nobody white can write certain kinds of characters, I just say, “Well, maybe you should stick to nonfiction.” (Laughs.) That’s where you’ll be happiest.

Finally, you play with the ideas of coincidence and chance in the book. One character says that coincidences are “merely normal events of low probability.” Have you had any life-changing coincidences like Jean and Attila do?

Oh, wow. That’s a big question! I have coincidences all the time, I have to say. But the thing is, I don’t think they’re coincidences. You should’ve tipped me off about this question!

Here’s one: I once walked into a bar in London and met a woman to whose dinner I’d been invited to as an extra guest two weeks before. I could hardly remember her name, and I hadn’t enjoyed the dinner too much—there was something going on, which was all to do with my ex-boyfriend not getting back together with his girlfriend. Which is why I was brought as “cover.” However, that woman was meeting a man that night, a friend, and when he walked in to meet her, he and I exchanged a few words. And in that very, very brief moment, we fell in love. And two years later, we got married. (Laughs.) I never would have met him otherwise. So I suppose that was mine.

Aminatta Forna/Samanta Schweblin, Inprint Margarett Root Brown Reading Series. Tickets $5. Stude Hall, Rice University, 6100 Main St. More info and tickets at inprinthouston.org.