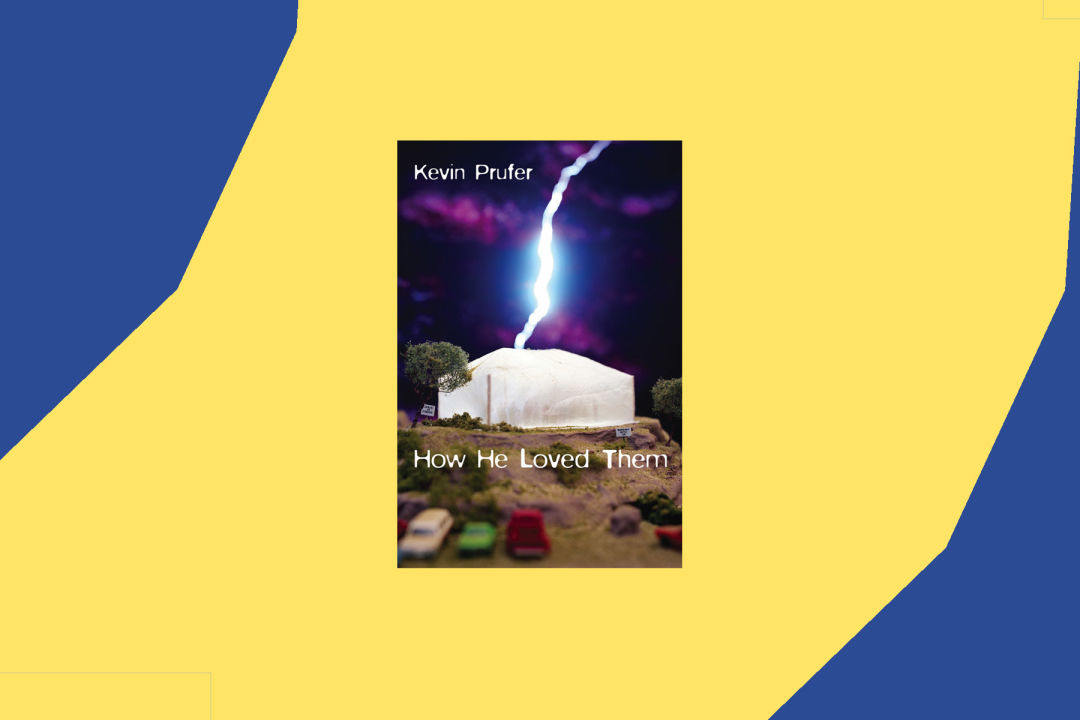

Kevin Prufer Explains Why Poetry Is Important

Image: Courtesy of Publishers

Kevin Prufer, who teaches in UH's creative writing program, will close out the 2017/2018 season of the Inprint Margarett Root Brown Reading Series tonight. The author of seven books of poetry—the most recent being this year’s How He Loved Them—Prufer will read alongside friend and fellow poet Rigoberto González. We caught up with Prufer to talk about his latest collection, finding beauty in violence, and the power of poetry before the event.

What was the hardest poem for you to write in How He Loved Them?

I have a copy of the book right here! Let me look in the table of contents. It’s interesting, because I don’t really think of poems as being hard to write or not hard to write. I start writing and just sort of work at it and work at it and work at it. One that was harder to get through than the others—“Could Someone Please Check on My Mother?”—for instance, took many, many weeks to compose. There were so many distant narrative threads happening simultaneously, so braiding those threads into one creation took a lot of time. Sometimes something will start as many different poems, and then I’ll realize they’re all in conversation with each other.

It’s funny: I recently opened up a computer file of the manuscript for this book. There are 34 poems in the book, and about 170 poems in this file. So most of the poems didn’t even make it into the book! (Laughs.)

There’s a thread of violence and vandalism that runs through the poems in How He Loved Them. Can it be difficult to find poetic beauty in ugliness, or is that something you like to seek out?

I often think that it’s easier to understand violence—political violence, personal violence—when we are offered its opposite, which seems to me to be beauty. I think it’s the same way that a black dot is clearer on a white wall than it is on a gray wall. I’m really attracted to the idea that a poem’s qualities, whether it be its music or the beauty of its images, might work in counterpoint to what the poem is talking about. That’s a much more interesting place to begin as a writer than to begin by writing an ugly poem about ugliness. In which case, you’re really just confirming what’s already implicit in the subject matter.

When do you know that you’ve got a new collection of poetry on your hands? Is it a process of accumulation, or something that you work toward?

Usually it begins by just writing and not worrying about a collection. Writing a book of poems is a weird and unnatural process. With a novel, you’re writing one work of art. With a painting, you’re painting one painting. But when you’re writing a book of poems, you’re really creating a bunch of individual works of art and then asking them to work together nicely. And they often don’t want to work together nicely. (Laughs.) And there’s no reason that they should work together nicely! One doesn’t go into an art museum and say, “I like every painting in this gallery. Wouldn’t it be great if I stitched them all together into one gigantic quilt?” That’s kind of what happens with a book of poems. I’ll write and write, and it’ll feel like I have about two-thirds of a book of poems that seems interesting together. Then I’ll try to write toward a complete book of poems. But I mean, I’m seven books in, and I still don’t have a clear answer to that. I have friends who will write a “project” book of poems. They’ll want to write a book of poems about Audubon or Matisse or something. I can’t do that. I have to sit down and write toward an individual poem, and then hope it’ll cohere into a collection. A lot of that is happenstance. And a lot of it is having a good editor, too. I have a good editor who can see when a poem doesn’t fit.

You’re speaking at the end of National Poetry Month. Why is reading poetry valuable?

I teach a class on this, so I’m going to try to distill a semester into a few sentences!

Go for it!

(Laughs.) I think that in my life and in all of our lives, we’re told all the time what to believe about complicated subjects. About politics, for instance, or about the news. And one of the things that poetry does very, very well is that it does not tell you what to believe. It helps you understand the complexities behind the belief. It understands that when you’re asked about a complicated question—about politics, your life, love, God, or religion—that any thoughtful person will rightly be pulled in many directions. And some of those directions are contradictory to other directions. What poems do is entertain that: with their white space, their images, their rhyme, their narrative, their metaphor. They allow for conflictedness and ambivalence. And I think that’s really important in the world, especially in a world where there’s a lot of attention given to “vote this way or vote that way.” A poem can say it’s OK to be conflicted and to simultaneously believe conflicting things and let us understand the complexities of questions. That’s what poems do best. And that’s what we don’t have enough of.

Rigoberto Gonzalez/Kevin Prufer, Inprint Margarett Root Brown Reading Series. Tickets $5. Stude Hall, Rice University, 6100 Main St. More information at inprinthouston.org.