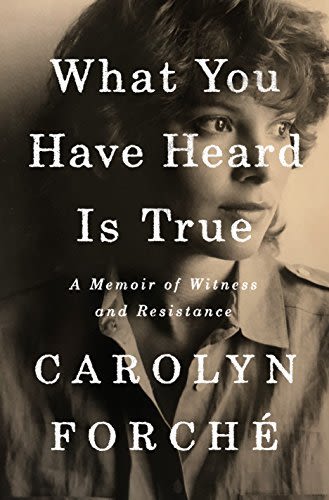

Carolyn Forché on Writing About Her Experience During El Salvador's Civil War

Carolyn Forché made her mark in literature with her poetry and translations, but her 2019 book, What You Have Heard is True: A Memoir of Witness and Resistance, called upon a different set of skills. It required her to dig decades into her past and fulfill a promise made to two friends. Forché was just 27 when a stranger showed up on her doorstep and asked her to join him in El Salvador to witness the political upheaval taking place there. She accepted, and her memoir, What You Have Heard is True, which is up for 2019 National Book Award, recounts her time in the Central American country during the beginnings of its civil war, which spanned from 1980–92, and how this choice changed both her life and her art forever.

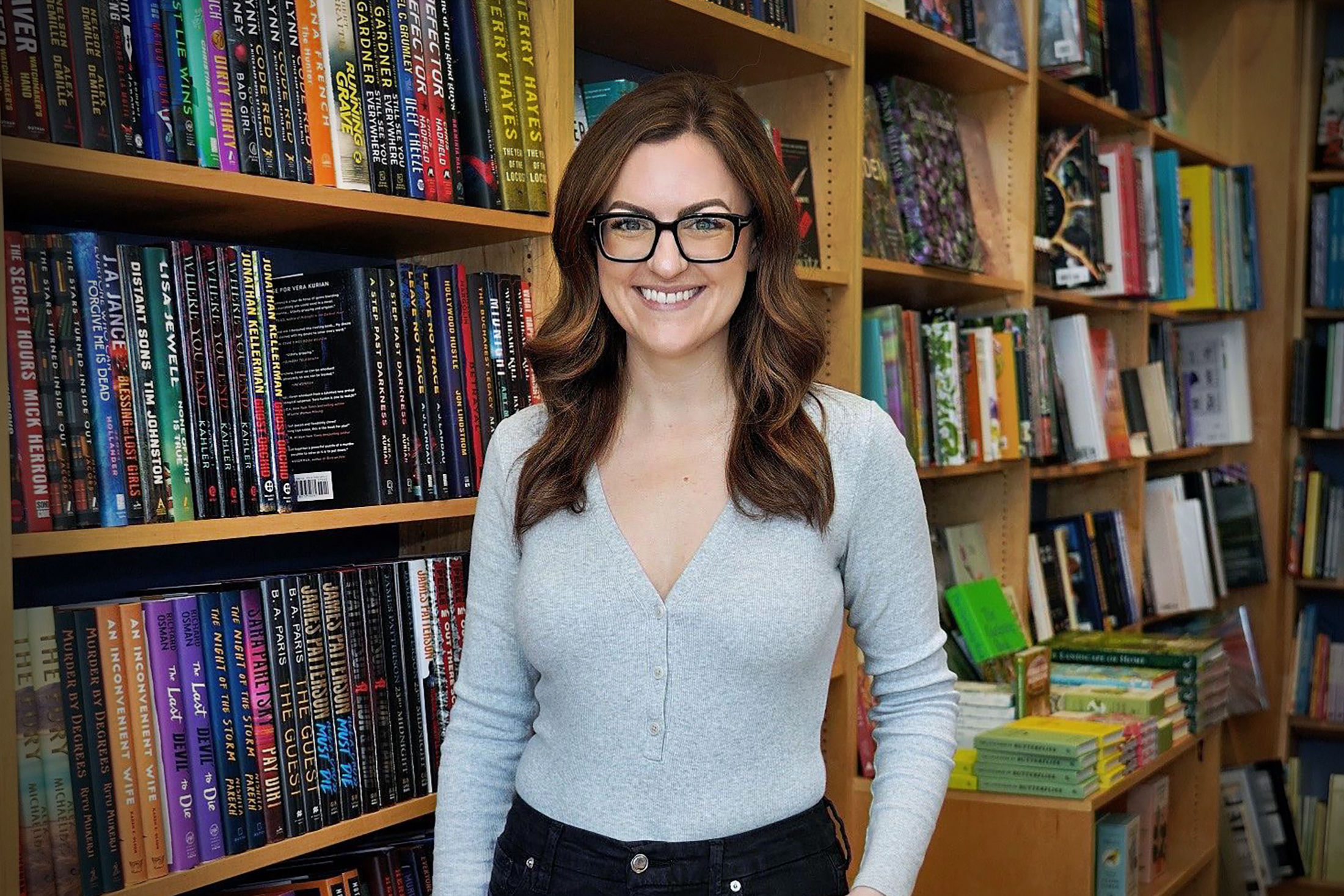

On Monday, Jan 27, Forché will read from What You Have Heard is True as part of Inprint’s 2019-2020 Margarett Root Brown Reading Series alongside Carmen Maria Machado. We caught up with Forché to talk about her memoir.

“Witness” is a common thread across your writing in various genres. How did that idea look or feel different when writing a memoir?

"Writing witness is writing in the aftermath of extremity. So, it’s not really something one can intend to do, and it’s not an identity. What we do is read for witness when we’re reading such work. In terms of writing the memoir, I believe there was considerable extremity involved in the experience, and that I am bearing witness to that. It’s of a piece with the rest of my work, although I haven’t really focused attention on my own work in that way—I’d rather study the work of others."

I think, like you said, applying that idea to your own work and your own life versus someone else’s work is very different.

"Yeah. It took me a long time to even begin writing this memoir. Most of the events took place between 1978 and 1980, and I didn’t begin writing the memoir until 2003. I didn’t feel ready to write it either as a writer or as a person who had somehow emerged intact from those years, capable of recreating them on the page. But then I realized that I had promised that I would one day write about it, and I was running out of time. I was already in my 50s when I started it.

"It also took 15 years to finish, partly because it was my first book-length work in prose, so I had to learn how to do that; and there were skills that I hadn’t acquired or attended to as a younger writer. I was a poet, so I knew nothing about structuring prose books. It took me quite a while to find the right structure for that book. And life intervened several times. Sometimes I procrastinated out of fear of what I was going to write next—either fear of inadequacy or fear of enduring its recreation on the page. There were lulls in the work. Sometimes I just simply didn’t want to write that next scene, and I didn’t know how to do it, so I’d wait and meditate on it, think about it, and finally, when I got pen to paper something would come out. It was a painful book to write."

It must be especially tough because the topic is so complex, and then you’re trying to figure out what your voice sounds like in this form you haven’t worked in before.

"Exactly. What I wanted to do was write it in such a way that the reader would never know more than what I knew at the time. So, the story unfolds the way that it unfolded for me, with all that complexity and confusion. And as I was at the time piecing together a great puzzle, I wanted the reader to feel that way, too, and to piece things together with me. I tried to preserve that uncertainty and confusion and complexity in the narrative. So, there are very few moments where the narrator steps back with hindsight or foresight of some kind.

There are moments of great tension throughout the book that you cut through by mentioning the pop culture of the time. The one that jumped out the most to me was the appearance of Abba’s “Take a Chance on Me” after a tense interaction. Was it important to remember those small moments of frivolity as you dug into your memories of such a tumultuous period of history?

"Yes. I was trying to make the time live again. And that, of course, includes popular culture—what was on the radio, the music that was playing. I remembered all of that quite vividly. My memories of that time are very precise. And there were strange juxtapositions, like carnage and Abba songs. (Laughs.) I wanted to include that, because to do that was to be true to what it was like. There were odd moments when you couldn’t believe you were hearing this particular song on the radio while you felt this might be the last moment of your life."

Toward the end of the book, you mention how your second book of poems took you across the country and gave you the chance to talk to people about the war in El Salvador. What You Have Heard is True reengages that same history, but in a completely different way. How has the experience of talking about this book been different for you?

"I’m talking about this book in a very different environment. At the time when my poetry book was published in 1981, the United States was supporting a military dictatorship, and by extension, the death squads that were operating during those years. The United States wanted to stick to its policy of support, and Americans, by and large, didn’t know very much about Central America at that time. Most of them had not yet heard of El Salvador—it was just coming into the news stories at the time when my book was published.

"But there was a considerable disinformation campaign, and some of it came from the U.S. government, which accused journalists of inventing stories. It was the early version of “fake news.” To speak to American audiences and publish in the literary world at that time was very fraught. And there were many people who disbelieved what I had to say or questioned it. That, for a young woman poet, was quite painful and disorienting.

"Today, I’m a mature woman, and I’m speaking in a very different environment. Literary culture is not so naïve anymore, and American citizens seem to know a great deal more, especially about Central America, because over the decades we’ve acquired this knowledge. Today, of course, it’s important to them because of the refugees approaching our border for asylum. People are very interested in those issues, whether they oppose open asylum granting or not. But we do bear a responsibility to the people who are today fleeing the aftermath of the war that we paid for. I don’t have time to go into all the ways that that’s true, but today I don’t face the same credibility challenges that I faced in the past. The situation is very different now."

Jan 27. Tickets $5. Alley Theatre, 615 Texas Ave. More info and tickets at inprinthouston.org

[This interview has been edited for length]