Jewish Deli Exhibit Tells Story of Hope at Houston Holocaust Museum

The delicatessen played a big role in how Jews rebuilt a life for themselves in America.

When curators of the Holocaust Museum Houston (HMH) entered the Kenny & Ziggy’s storage room where Ziggy Gruber keeps his extensive deli menu collection, they were more than a little daunted. Over the years, the third-generation deli man has amassed thousands of menus from the early 1900s to present day, which he keeps very organized, tucked in art portfolios for ease of browsing. Gruber jokes that his collection could warrant an exhibit of its own, but for now, a small selection is displayed in I’ll Have What She’s Having: The Jewish Deli, on show at HMH until August 13.

New York City and Los Angeles are top of mind when people think about Jewish American culture—and where to find a great bagel or knish. Houston, not so much. But the deli exhibit and the museum itself are a testament to the city being way more of a Jewish hub than people give it credit. For a few years in the early 1900s, a coordinated emigration plan called the Galveston Movement brought 10,000 Jews through the island’s port. The idea was to redirect these refugees, who were fleeing pogroms in Russia and Eastern Europe, away from crowded coastal cities to the middle of the country. Some traveled north to places like Kansas City and St. Louis, but many stayed in Texas.

HMH was founded in 1996 by 20 survivors of the Holocaust who saw a need for such a museum in their home of Houston. The permanent galleries guide visitors through war and genocide in great detail, while the temporary exhibits focus on continuing stories of Jewish culture. I’ll Have What She’s Having, a reference to that famous When Harry Met Sally scene, was developed by the Skirball Cultural Center in Los Angeles, where it was on show in 2022 before traveling to New York, now Houston, and eventually Skokie, Ill. The exhibit is HMH’s first that revolves around food, but Alex Hampton, the museum’s changing exhibitions manager, is quick to say that it’s not just about sandwiches.

“A deli really embodies everything that is Jewish culture,” Hampton says. “It creates community, offers jobs to people coming to the United States who didn’t know anybody, could barely speak English, and really needed to find that community again after they lost everything in the Holocaust.”

HMH’s main subject matter is dark, but it’s part of Hampton’s job to cultivate a narrative of hope and resilience, and show how Jews rebuilt a life for themselves in the U.S. Food is a great entry point to tell that story. While the museum doesn’t have concrete numbers, chief marketing officer Robin Cavanaugh has heard deli exhibit visitors comment that it was their first time in the museum. “I think ‘a community forged in food’ is a common denominator everyone can relate to,” she says. Hampton adds that many student tours have come through the space as well.

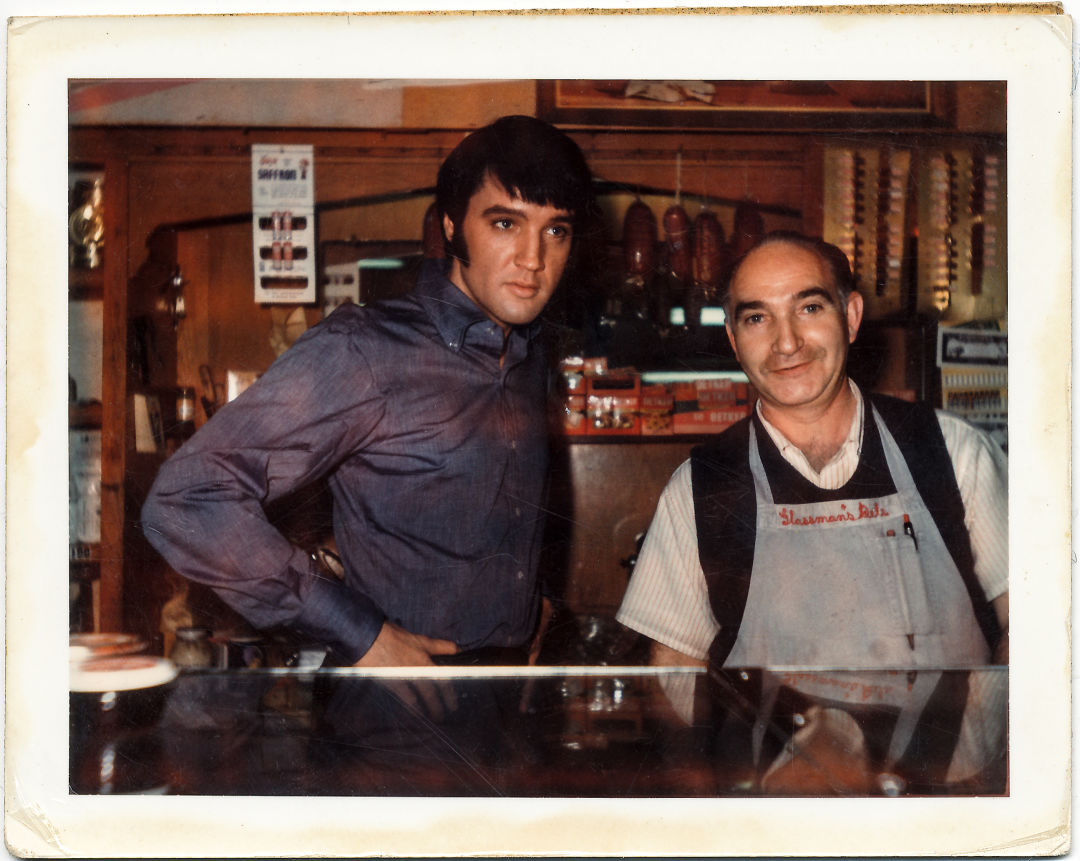

Elvis Presley with deli employee Joe Guss at Glassman’s Deli and Market, Los Angeles, CA, 1969. From the Bonar Family Collection.

I’ll Have What She’s Having begins with the first wave of Jewish immigration from Eastern Europe to the United States, in the late 1800s and early 1900s. It goes on to chronicle the evolution of the deli, from roving carts on the streets of New York to what it is today, showing how Jews brought their culinary traditions and adapted them to their new home. Old posters, photographs, and artifacts highlight the growth of the deli within American culture through marketing and advertisements. Katz’s Delicatessen’s famous “Send a Salami to Your Boy in the Army” campaign, which raised more than a million dollars’ worth of war bonds during World War II, has a spot on an exhibit wall alongside matchbooks from delis across the country. Several large prints of the “You Don’t Have to Be Jewish to Love Levy’s” ads that were everywhere in the New York subway in the ’70s appear too. An old menu from Alfred’s acts as one of the local nods to Houston—Hampton says all the museum’s docents told him it was the place to go back in the day, before it went out of business in the ’80s.

In the exhibit’s main room, the tales of famous deli owners from across the country are interspersed with mannequins wearing traditional deli uniforms as well as short films to engage visitors. One shows clips on a loop of delis being portrayed in pop culture, including the famous orgasm scene in When Harry Met Sally—which, when it reverberates across the room, is either funny or awkward depending on who’s in there with you.

Ziggy Gruber loaned a giant Kenny & Ziggy’s sign and several historical menus to the exhibit.

Finally, the historical menus from Ziggy Gruber’s collection sit in the back, showing the delicatessen’s reach from Pumpernik’s in Miami Beach to D.B. Kaplan’s in Chicago, and even a menu from Jo Goldenberg, the legendary Paris deli that was bombed in 1982. Hovering over the collection is a giant Kenny & Ziggy’s sign, also donated by Gruber. When he moved his restaurant’s location in 2022, he put the original sign in storage—you never know, he may need it someday, he thought.

The new Kenny & Ziggy's location on Post Oak Boulevard is bigger and better.

Image: Courtesy Kenny & Ziggy's

The new location on Post Oak Boulevard is just down the street from the old one, but provides a much bigger space for Gruber’s New York–style deli, complete with a sprawling soda fountain, walls plastered with Broadway show posters, and cases lined with cakes and cookies twice the size of your face. The laminated, trifold food menu is equally huge: 22 inches in height, towering over diners’ heads as they peruse the options—as Gruber puts it, “it’s like reading the whole Haftarah.”

While many deli menus these days are concise, Gruber wanted his to be expansive, sampling many Jewish foods across the diaspora, from Ukrainian meatballs to Hungarian-style stuffed cabbage. More modern creations, such as a decadent sandwich of brisket between two latkes, also have a space on the menu. Gruber frequently offers specials, and tries to bring back lesser-known recipes that have mostly disappeared from menus in the U.S. Recently, he’s also been experimenting with adding Sephardic dishes (Gruber, as a Jew of European descent, is Ashkenazi), because he’s noticed that younger diners “like to eat the dips and stuff like that.”

Anne Russ Federman serving customers at New York’s Russ & Daughters, with Hattie Russ Gold in the background, 1939. From the collection of Russ & Daughters.

As Gruber and others across the country have kept the Jewish American deli alive, it’s a genre of dining that is shrinking. Before the COVID-19 pandemic, Gruber says there were 140 delicatessens in the country; there are now 105. He attributes this to the increasing costs of operation, but it’s not all a sad story. As the exhibit recounts, many Jewish immigrants opened delis and worked hard in them so their children wouldn’t have to.

Gruber makes a parallel to Houston’s Jewish community, comprised of well-educated doctors, lawyers, and other professionals who have become very successful, but are also very philanthropic. “They do a lot of mitzvahs,” he says. This success has in turn supported longtime local Jewish staples like Kenny & Ziggy’s, New York Deli & Coffee Shop, and Three Brothers Bakery, and has also allowed Houston’s Holocaust Museum to not only come to fruition in the first place but also to thrive.