Houston Author Jennifer Mathieu’s New Book Is All About Eco-Anxiety

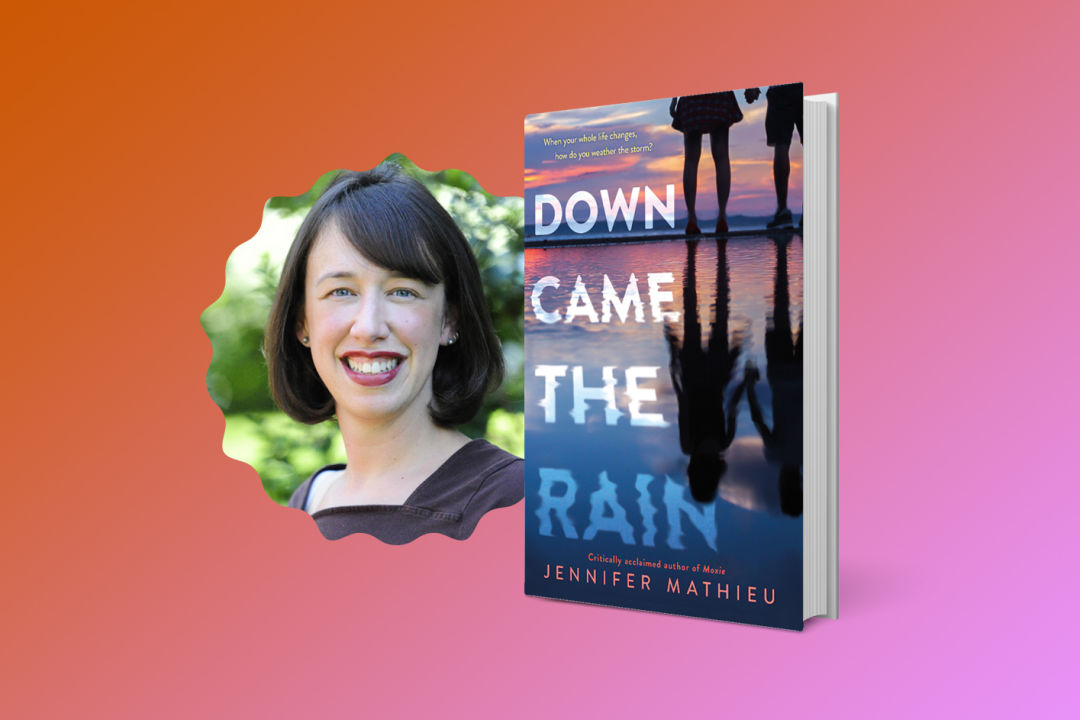

Down Came the Rain is the seventh book from local YA author and Bellaire High School English teacher Jennifer Mathieu, the acclaimed author of Moxie.

Eco-anxiety is everywhere these days. The planet just went through its hottest August on record, and that was felt nowhere more than in Houston, which saw triple-digit days through much of the summer. As we approach cooler weather, Winter Storm Uri is likely on the minds of many: the 2021 freeze cost the lives of 246 Texans and left 90 percent of Harris County residents without power at its height. Some families are still struggling to recover from the toll it took on their homes—not to mention their savings accounts. Before all of this was Hurricane Harvey, a nightmarish deluge that reminded us all of just how vulnerable Houston is to flooding and of the precarious future our city faces as climate change continues to ramp up.

While many adults suffer from eco-anxiety, young people are affected by it the most. Over the past few years, many of them have realized how small they are in the face of an impending doom that will affect them for the rest of their lives. That is, if substantial work is not done to curb the effects of climate change. Local YA author and Bellaire High School English teacher Jennifer Mathieu, the acclaimed author of Moxie, has a new book coming out on September 26 that perfectly encapsulates the existential dread suffered by many eco-anxious young adults.

The book, Down Came the Rain, is set in the aftermath of Hurricane Harvey and tells the story of Eliza Brady, an 11th grader who is forced to transfer to a new school after Harvey destroys her home. As she settles into life at her new campus, Eliza meets Javier Garza, another eco-anxious youth, and the two throw themselves into climate activism. Through the course of the book, the connection between the two young protagonists grows as they find love in the face of climate adversity.

Mathieu, now in her 19th year as an educator, has been teaching for long enough to see a shift in how preoccupied her students are with climate change. When her first book, The Truth About Alice, came out in 2014, she says her students discussed climate change, but it wasn’t front and center in their minds like it is for the teenagers she teaches today.

“If I asked my kids to pull out a piece of paper numbered one to three and asked them to write down their top three worries, I bet for a lot of the kids climate change would be in that top three—maybe even number one for a lot of them,” Mathieu says.

Mathieu, who lives in Westbury, is a sufferer of eco-anxiety herself. During Harvey, she and her husband took shifts sleeping so they could watch their house for flooding. Although large portions of their neighborhood flooded, their house ended up being safe—a little island in the middle of the floodplain. It was all too close for comfort, and Mathieu remembers feeling guilty about the fact that her house didn’t flood when those of so many of her neighbors did. She ended up with a bit of Harvey-induced PTSD. “It probably took me about two years after Harvey to be able to enjoy the sound of rain,” Mathieu says. In her book, Javier has full-blown panic attacks whenever it rains and seeks counseling from a social worker to learn methods to cope with his fears.

Climate change is a complex issue to unpack in a YA novel, and Mathieu wanted to make sure that there was a dialogue on class and race in the book. When climate disasters like the 2021 winter storm strike, it’s often the poorest among us who are hit the hardest, since it’s more challenging for them to financially rebuild or access aid. “A lot of the poorest people on the globe who have contributed the least to climate change are going to feel the effects the most,” Matthieu says. Throughout the course of Down Came the Rain, the character of Eliza, who is white and comes from a solidly upper middle-class background, is forced to come to terms with her privilege and learn just how much things like class and race intersect with climate change.

At one point in the book, Eliza, who has formed an on-campus environmental activism group, slashes the tires of several of her school’s buses because she is enraged by how much carbon dioxide they spew into the atmosphere. But before her little act of eco-vandalism, Eliza didn’t stop to consider how not having access to buses would affect her school’s poorest students, who might not be able to get to school without them.

“She slowly becomes aware of her privilege,” Mathieu says. “She’s not a bad person, she’s just a privileged white girl and she’s just having to learn. I felt that it would be meaningful for readers from all walks of life to be able to see how those things intersect.”

Toward the end of the book, Eliza has a huge confrontation with her dad, who works for an oil and gas company. Young and idealistic, she doesn’t understand why he can’t just quit his job. Her dad is a caring person who believes that climate change is real, but he’s worked in oil and gas his entire life and doesn’t know any other way to support his family. It’s a scenario that’s easy to imagine happening in real life in homes across the city. Houston is the energy capital of the world, and its economy will have to eventually shift away from Big Oil if we are going to address climate change on a local level. For many, that would seem impossible. Mathieu herself isn’t sure how such a massive shift would work, and says Houston’s potential oil-less future raises some prescient questions.

“How do we untangle ourselves as a country and as a world from fossil fuels? How do we do it? It’s very difficult,” she says. “I certainly don’t have the answers, but I do think that having a book that brings it up and brings it to the forefront of people’s minds, especially young people’s minds, is really important.”

While she’s leaving the big questions like oil and gas divestment to the experts, Mathieu is hopeful that through reading Down Came the Rain, young adults will be able to better come to terms with their climate angst. “We look to fiction to try to make sense of things,” she says. “My big goal with this book is to help young people be able to name that eco-anxiety, and if they have it, to feel less alone.”