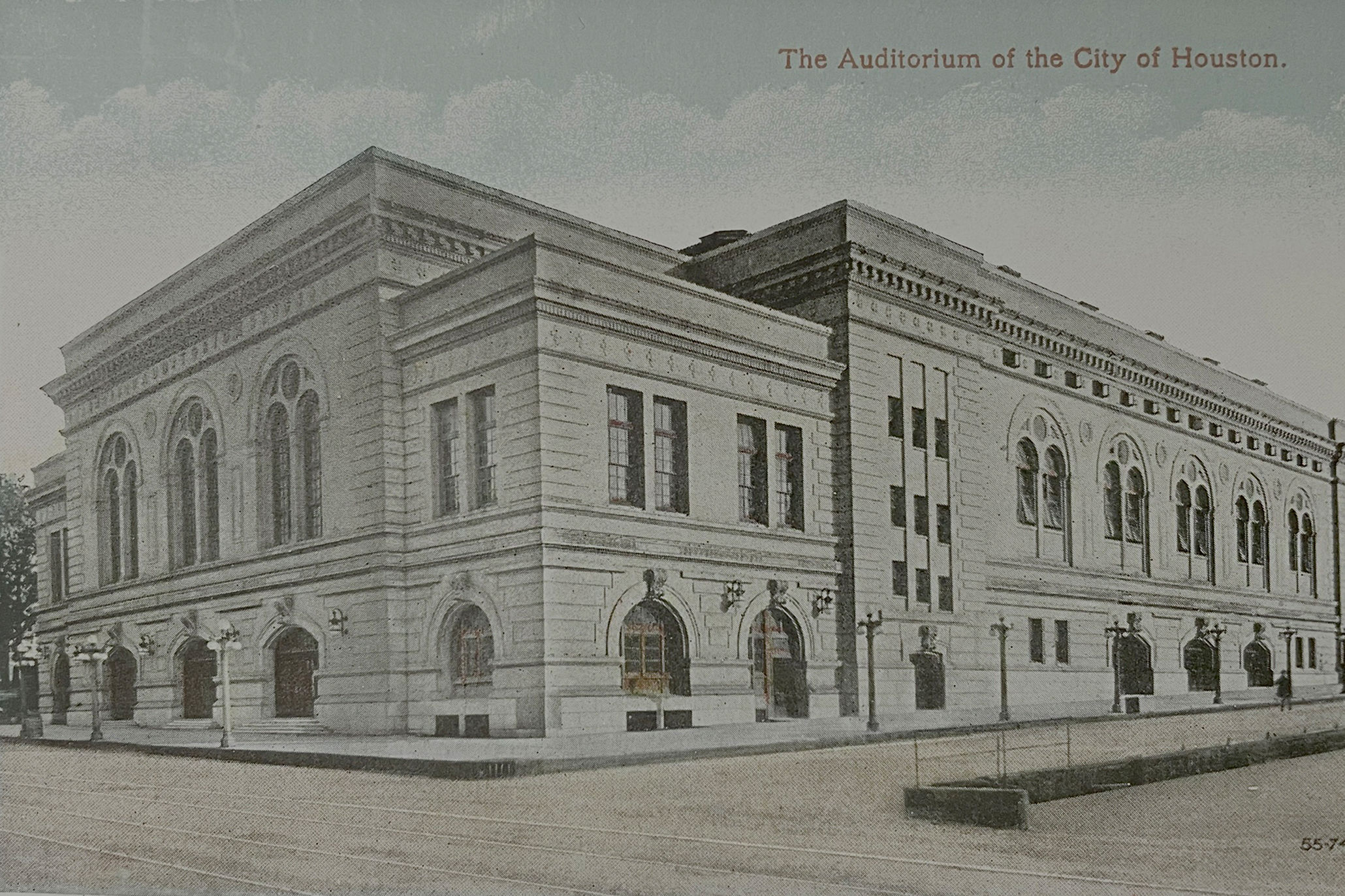

That Time A Would-Be Cattle Baron Lost Everything

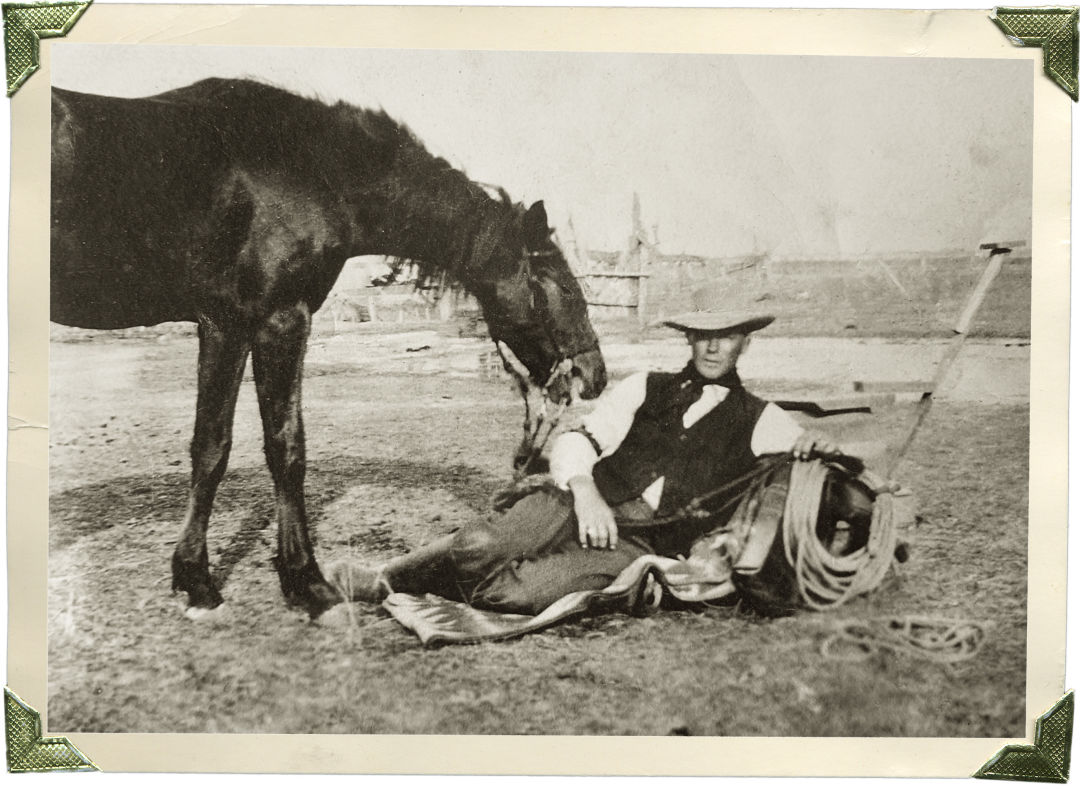

My great-grandfather, Christian Meineke

Image: Dianna Wray

THIS IS HOW THE STORY BEGINS, NO MATTER WHO IS TELLING IT. My great-grandfather wasn’t even a grandfather yet, just an ambitious young man: the youngest son of land-poor German immigrants who saw an opportunity when the Hermann brothers were looking for a partner in their cattle operation. Christian Meineke had grown up in Houston with only a first-grade education, but he was no fool. The Hermann family, the donors behind the first hospital that would ultimately give rise to the Texas Medical Center, had made fortunes before.

Depending on whom you ask, this all occurred sometime between the start of the Great War and the lean years that would slide into the Great Depression. My family has never been exact on the timeline, but we’ve always placed it roughly a century ago, when the world was unsettled and life in Houston was hard, and we always retell the story when times get hard again.

The way I learned it, my great-grandfather scraped together every cent he’d saved up, a hard job for a cowboy who was already supporting a wife and their sickly son, and sank it into buying a piece of the Hermann brothers’ cattle herd. They were bringing in a new breed, Brahmans from India, with an eye toward crossing the bovines with some native Texas steers to create a more durable animal. Even when other Houston ranchers and farmers were struggling (the Great Depression started early for people working the land down here), the venture was practically a sure thing.

My great-grandfather and his business partners bought 500 cattle, and Christian rode the trail himself to bring the herd in. He was out every weekend, every spare moment he had, looking over those foreign cows. Studying them, he must have believed the money at his hip—a ten-dollar bill his wife, Loretta, had sewn into the plain leather belt he always wore, their “just in case” money—was soon not going to be necessary. A new future was rising up out of this pasture, one where Loretta wouldn’t have to work so hard. Christian wouldn’t have to pull young Robert out of school the way his own father had. They might have another child, even. (They would, and she would be my grandmother.)

Houston was still just a wide spot in the road, but he might be someone in this growing town: Christian Meineke, the cattle baron. Even then Houston was the kind of city where such meteoric rises were possible. The cows would have lowed and murmured as they chewed their cuds, the sounds drifting over the fields to the slim, sunburnt man at the fence who had bet everything on them.

And then it all went wrong. Christian went to bed one fall night secure in the promise of the cattle just outside the city, but when he woke up the next morning a storm had blown in, and temperatures had plummeted. The Brahmans could take heat but couldn't stand the cold. Most of the herd was dead, and every penny of his investment was gone. “His partners had more money,” my uncle has always told me, “but he’d earned every cent he’d put in riding the rodeo circuit. There was nothing else.”

My great-grandfather took it all in that morning. Maybe he thought of his son’s doctor bills—the boy had TB—or the money he owed at the shops in town. We don’t know, and that has never been a part of the story. What we do know is that he remembered the cash at his hip, pulled off his belt, and started over again. But that’s not where the story ends.

He used that money to survive until he found work. He quickly got a job as the butcher at a local grocery, broke horses on the side, and every weekend saw him back riding the rodeo circuit throughout the Great Depression. Brick by brick he rebuilt his future, buying a neat clapboard house on Driscoll Street, and hiring a woman to help my great-grandmother after my granny was born. “You see,” my mom always says at this part, “he had been down before, and he would be down again, but that never stopped him.”

I’ve been thinking of him a lot lately, as we at Houstonia have been putting together our feature focusing on the resilience of this tenacious, wonderful city. To me he represents everything that makes Houston what it is, the reason I have so much faith in our town’s ability to handle anything life throws at us. He was the definition of resilient. Years later he would even tell that story—about the young man with so much hope, who woke up one morning and had lost everything—and laugh about it. “You can go to bed a rich man,” he would say, “and wake up a poor one. I’ve done it. But it’s what you do once you’ve woken up that shows the world what you’re made of.”