Dredging Up Civil War History in Galveston Bay

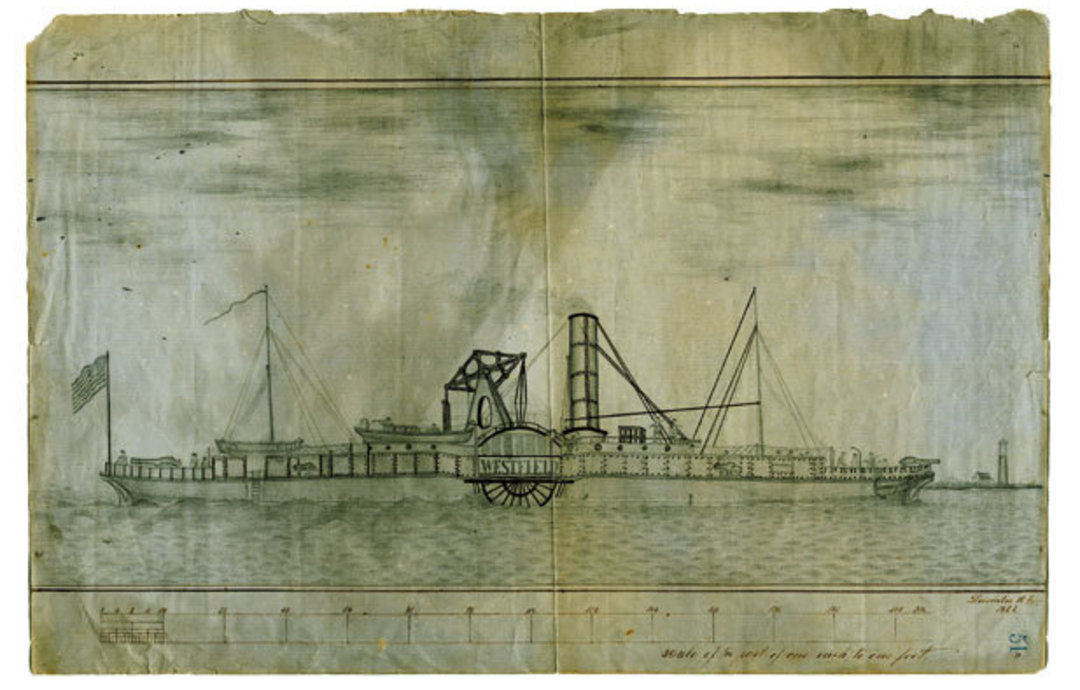

USS Westfield, a Civil War ship that sank in the Battle of Galveston in 1863. Courtesy of Conservation Research Laboratory, Texas A&M University; Unknown artist, courtesy Memphis and Shelby County Room, Memphis Public Library and Information Center

Texas A&M’s Conservation Research Laboratory is housed in a low-slung warehouse that looks like a mechanic’s garage about 10 miles northwest of College Station. Inside, the air is pungent, part seawater and part soot, as a team of archeological conservators sits trying to piece together the bones of various dinosaurs, although in this case the bones are twisted chunks of jet-black iron and the dinosaurs are ancient warships (by which we mean Houstonia ancient: the 17th century).

“When you go home at the end of the day you’re literally covered in marine mud,” says Justin Parkoff, a project manager leading us past dozens of 10-foot wooden planks from LaBelle, a French ship that sunk off the coast of Texas in 1686. Our destination is a set of shelves full of what look like pieces of a WWII-era tank. In fact, they belong to the USS Westfield, a Civil War ship that sank in the Battle of Galveston in 1863. Having run aground after a Confederate surprise attack, the Westfield was destroyed by its Union crew so it wouldn’t fall into enemy hands.

After receiving permission from the US Navy—which Parkoff says considers the ship a “war grave”—he and his team have been working to reconstruct the Westfield, which was discovered by the Army Corps of Engineers in 2009. Though one of the ship’s original cannons is already on display at the Texas City Museum, they hope to add the vessel’s boiler and engine, as well as some personal effects from the crew, in December.

“Nowadays we have all this modern technology,” says Parkoff. But the men tasked with restoring it originally—the soldiers who repaired the Westfield when she was injured in battle—“had to do it by hand.” This often led to ingenious improvisation: part of the boiler’s fire grate appears to be made from pieces of train track lifted from Confederate railways.

“When it comes to Civil War ships, what comes to mind for most people are ports in places like Virginia and South Carolina,” Parkoff says. “Most people in Houston probably don’t realize that very real nautical fighting was going on in their backyard too.”

He points to a bowling ball–size cannonball, one of 24 Westfield shells that had to be defused by members of the Marines for fear they might still be live. Hollow and packed with gunpowder, they were designed to explode like a grenade after puncturing an initial hole in an enemy vessel. The goal: to kill as many crewmembers as possible while limiting damage to the ship.

Parkoff says the A&M team regularly finds bone fragments, belt buckles, and other personal effects infused in the wreckage. What, we wonder, does the Westfield wreckage tell us about 1860s warfare?

“They were getting very clever at finding crafty ways to kill each other,” he says.