Talking Jazz with Rick Mitchell

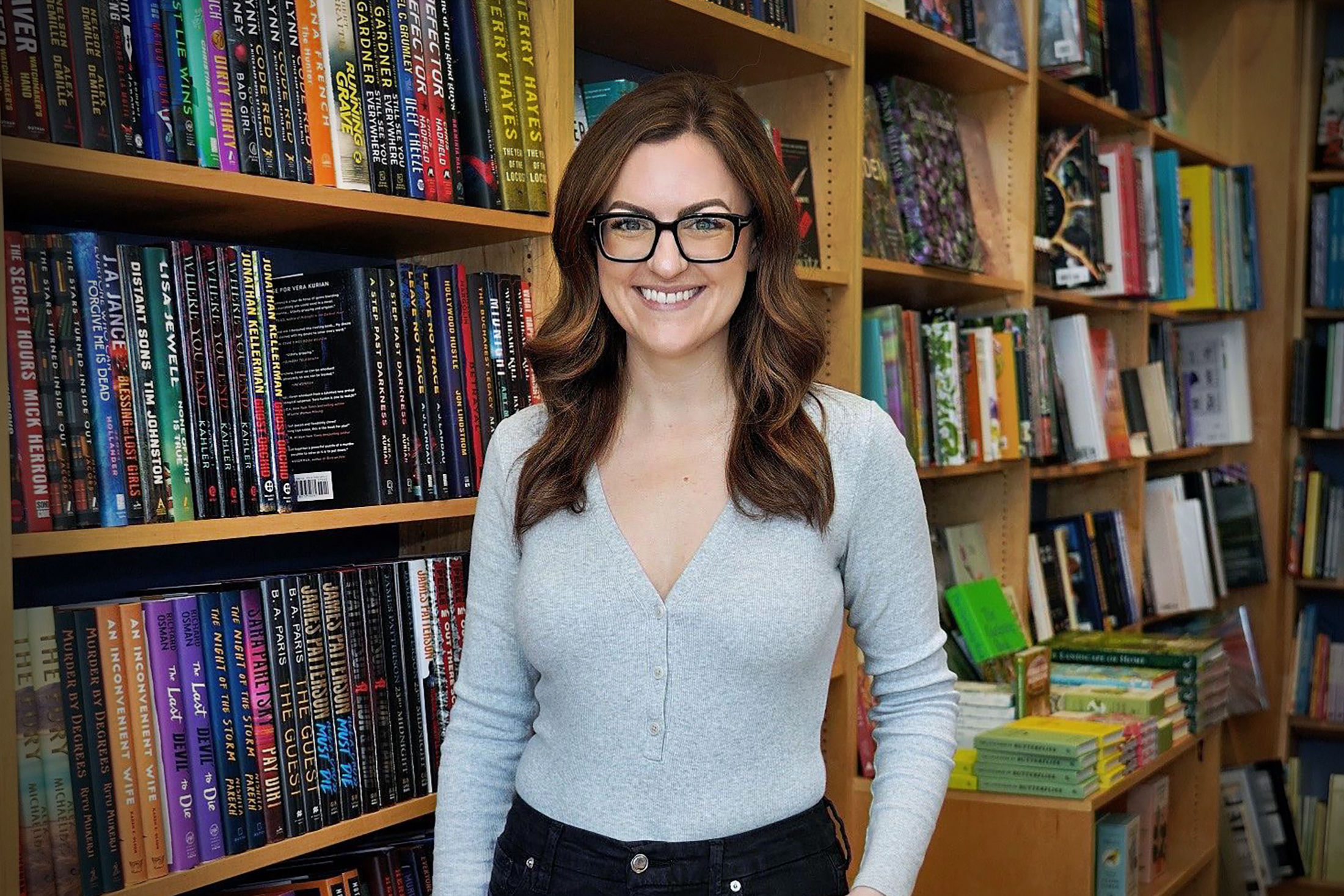

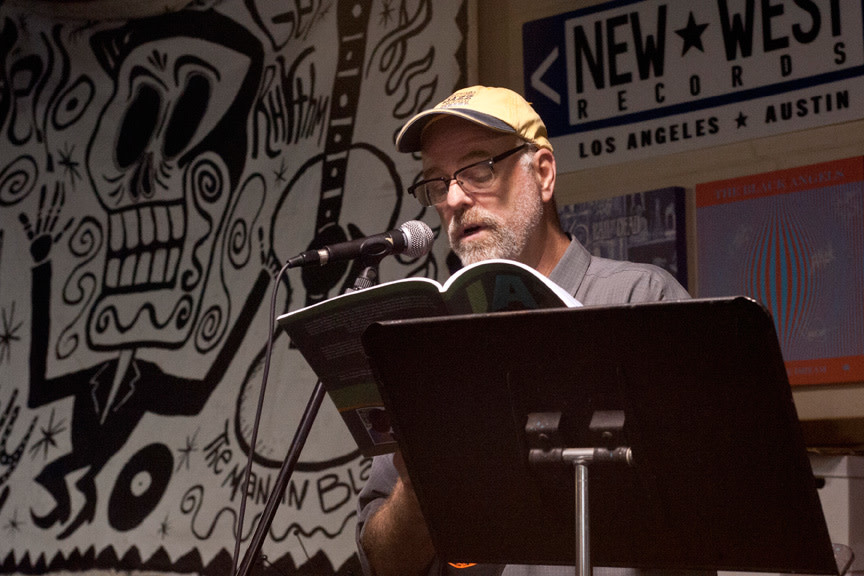

Rick Mitchell reading at Cactus Records

Image: Justin Mitchell

Rick Mitchell is a writer, educator and musician based in Houston. He has worked as a popular music critic for the Houston Chronicle and as a curator for the Houston International Festival. He currently teaches English at Lamar High School and hosts a radio show that airs at 2 p.m. on wclk.com and 91.9 FM in Atlanta. Last year, he published Jazz in the New Millennium, a collection of program essays he composed for the Da Camera jazz series over the course of 14 years. The book is available at rickmitchell.us, Da Camera of Houston, Cactus Music and Brazos Bookstore. I met with Rick at his Oak Forest home to discuss his career as a music critic and listen to records. It was the most fun I’ve had talking about music in quite some time. What follows is an edited version of our conversation.

Houstonia: How did you become interested in jazz music?

Rick Mitchell: I started listening to jazz seriously in high school. There was this FM underground radio in LA and they would have a Saturday night blues show, where I would hear B.B. King and Albert King, and rock bands like the Paul Butterfield Band and the Doors. There was extended soloing, which kind of prepared me [for jazz]. Plus, I knew “Mood Indigo” by Duke Ellington from when I was five years old. But I went to see a concert with the Steve Miller Band, Lee Michaels and the Charles Lloyd Quartet (with Keith Jarrett, Cecil McCbee and Jack DeJohnette). It was a Bill Graham concert in LA. Charles Lloyd just blew my mind, and I went out and bought Forest Flower, which I still have. That just kind of opened it up. And then fusion started happening after that with Miles [Davis] and the Crusaders and, on the rock side, Frank Zappa and Santana.

Houstonia: So you grew up in California?

Mitchell: Yeah. I was born in Northern California and then went to high school and college in Southern California. Then when I got out of college I moved to Portland, Oregon, where I kind of broke into radio and worked my way up the food chain from the hippie underground weekly to the more mainstream weekly to the afternoon daily to the morning daily. And I moved to Houston in 1989 basically as a career move to take a job at the Houston Chronicle. And even though I haven’t had that job in 15 years, I’m still here.

Houstonia: Do you remember Southern California as a musically rich environment in those days?

Mitchell: No, I just always gravitated to it. I remember there was a group called The Exciters that did a tune called “Tell Him” and there was this little metronome on there that went “bum-boop, bum-boop.” I was out to eat with my parents and my sisters and I’m just transfixed by the car radio. They’re like, “Go on into the restaurant,” and I’m like, “I’ll be in in a minute, I need to finish hearing this.” I’m eight years old, maybe. It was like a music critic being born, 'cause I’m sitting there thinking, “Man, that is great production!” When I got to college, my freshman English teacher said, “You should write for the [school] paper, you’ve got talent.” So I volunteered kind of as a music critic/reporter. I became the political columnist later on, by the time I graduated. Rolling Stone magazine just started being published. I probably at some point discovered Downbeat. I didn’t really want to be a critic. I wanted to be Woodward and Bernstein, but I knew a lot about music. So when I got to daily papers, I got kind of pigeon-holed.

Houstonia: What was Portland like when you were living there?

Mitchell: It’s the same now kind of as it was then. My band, it was like an all-star band. Everybody had their own band [and] they’d be working on weekends, so we could only work [together] on Sunday nights or Tuesday nights. And sometimes we’d have opening acts on for us and we wouldn’t hit the stage until 11:30 on a Sunday night. It’s like, who were all those people [in the audience]? They could not all have been selling blow to each other. But when I go to Portland now—my daughter lives in Portland—it’s the same thing.

Houstonia: Were you writing about jazz in Portland?

Mitchell: Yeah, and I was playing it on the radio. I’d kind of start out with some funkier stuff and then by 2:30 in the morning I’m playing Sun Ra. At that time, Portland did not have a commercial black radio station, and so the show I came on after was like an R&B show. I dedicated the book [Jazz in the New Millennium] to a guy named George Page. He was the Master Blaster. He was on from 2 to 6 in the afternoon, and he used to let me come down and watch him work. He’d been in the army. He’d been a professional football player in Canada. He was kind of like a black John Wayne guy, a tough guy. But he loved jazz and blues. I remember one time I was playing Sun Ra and he called me—he used to call it yang music—and I’m like, “I thought you didn’t like this stuff,” and he said, “Yeah, but this sounds good” [laughs]. I remember one time he was playing Horace Silver, “Sister Sadie.” There’s this tenor solo on there by Junior Cook and it’s just sweeping me away. And I opened my eyes and [Page] is just staring at me like, “Ah, yeah, okay. Passed it on.”

Houstonia: So you later got hired to cover music at The Houston Chronicle?

Mitchell: Yeah. Bob Claypool, who had been a longtime music journalist here, had jumped papers from the Houston Post to the Houston Chronicle. He had a heart attack or a stroke and died, and I basically inherited his gig. They needed somebody who could cover both country music and jazz, because they already had a guy, Marty Racine, who was primarily covering rock. And then when I got here I realized that nobody was covering Luther Vandross or Anita Baker or hip-hop, so I did that too.

Houstonia: Do you think of yourself primarily as a jazz writer?

Mitchell: Back in the 1970s in particular the generation of jazz critics that had come up in the '40s and '50s—Ira Gitler, Nat Hentoff—a lot of those guys really hated rock n’ roll because they thought it had commercially killed jazz. How could I hate rock n’ roll? I grew up on the Beatles and Chuck Berry. I love rock n’ roll, so I could never relate to that. But I did have this split in my head for a while in the '70s, where if it wasn’t bebop or avant-garde, I had no use for it. I would sort of secretly listen to the Rolling Stones or Merle Haggard. I remember [my girlfriend at the time] coming home, and I’d be listening to Waylon Jennings, and she’s like, “You’re regressing” [laughs].

Houstonia: I think all serious jazz fans or critics have that double mind. There’s the sense that you’re betraying jazz when you have those excursions off into hip-hop or pop music.

Mitchell: It’s much less so now. To a certain extent it’s healthy in that somebody like you or me, you have to sort of have an immersion. There’s too much to know. If you don’t make it your main focus for a while you’re just going to be kind of dabbling. But it doesn’t mean—sorry Wynton [Marsalis]—that that’s the only thing you can listen to.

Houstonia: Jazz can be difficult to get into because it comes with this whole history or tradition. People might not know where to start, and that’s not necessarily the case with pop music.

Mitchell: No, I don’t think it comes with the same weight. Like I point out in the introduction to the book, I think jazz is weightier in that it can be seen as the classical expression of African-American vernacular music. Or you don’t even have to say African-American, you can just say American so long as you qualify that all American music is to a certain extent African-American. So it does have a higher potential difficulty factor. And people feel, I think, intimidated. If I’m sitting here and somebody puts on Lester Young and then they play Coleman Hawkins, I’m going to know which is which. Most people aren’t, especially most people my age or younger because those guys were dead. So it takes a lifetime of ongoing [engagement]. But at the same time—in any form of music—people tend to latch onto something when they’re 18 and they never go past it, like the people at the Journey and Foreigner concerts. And jazz is the same way. There probably isn’t a Thelonious Monk out there right at the moment, but that doesn’t mean there’s not all kinds of stuff that’s being made that’s, in my opinion, as good or better as anything else that’s being made now. You don’t have to hold it up against Thelonious Monk. You don’t have to hold it up against anything. You just have to kind of keep your antenna up.

Houstonia: How has Houston nurtured you as a writer?

Mitchell: Waylon Jennings once wrote a song called “Bob Wills is Still the King,” where it says “you just can’t live in Texas unless you got a lot of soul.” Both the Geto Boys and Lyle Lovett came up on my beat, and I could relate to both of them. You have to be able to appreciate artistic merit across styles and genres.

People don’t gravitate to Houston because they love music. They gravitate to Austin or New York or San Francisco or somewhere else. But if I was in San Francisco or New York, there would be 20 other people with my resume. There aren’t here. So when I left the Chronicle, I had an opportunity to first work as a music curator with the International Festival and then book the thing for several years. That was a very creative process. It was creatively rewarding to be able to take a budget and curate something that truly made a statement about our city being an international, multicultural city.

Houstonia: What made you decide to quit working as a full-time journalist?

Mitchell: For the most part, I’d been a daily or weekly paper journalist for twenty years, and I could sort of sense the way the wind was blowing. I was teaching at U of H and realized that not only did I enjoy it, I was good at it. Plus I had this book [Whiskey River (Take My Mind)] I wanted to write. So I thought, instead of writing full-time and teaching on the side, maybe I could just flip it and teach full-time and write what I really want to write about. Right now I’m teaching high school full-time. [Jazz in the New Millennium] came out August 1, and my job at Lamar High School started the next week.

I just really wanted to get jazz back in the discussion. When young, musically hip people talk about the music that’s really exciting them now, jazz is not part of the discussion as much as it should be. And that’s a shame. It doesn’t necessarily have to be current jazz. Go listen to John Coltrane Live at the Village Vanguard. Listen to Thelonious Monk. But there’s great music being made now out there. It’s not supposed to be commercial music. Ira Gitler and Nat Hentoff don’t have to blame rock for economically killing jazz. Since Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie, it hasn’t been dance music. It’s not supposed to compete with popular music. I do think that if it was presented better, for lack of a better word, that the proportion of people who listen to jazz could probably go up from 2 percent to 5 percent, which would make a huge economic difference.

Houstonia: What other forces do you think ultimately keep jazz from becoming part of the discussion?

Mitchell: I think we’ve kind of had a dumbing down of popular culture with reality TV shows all the time, with radio conglomerates with highly segmented, highly restrictive playlists, and newspapers going out of business.

When so much great music happened—including jazz, even though it wasn’t necessarily a commercial high point—in the 1960s, there was a radical undercurrent in our society that momentarily broke through into the mainstream. I mean there’s no way that somebody like Jimi Hendrix would be a pop star now. I was just listening to Hendrix at Woodstock and it’s kind of sloppy but it’s out there. It’s wild. It’s unhinged. It’s just sound crashing. Yet “All Along the Watchtower” was on AM radio. I think maybe we need to have another true crisis to inspire that level of urgency in the music. And I hope jazz or jazz-trained musicians are there to answer the call.