Through the Losing Glass: What the Recycling Conundrum Says About Houston

Image: Shutterstock

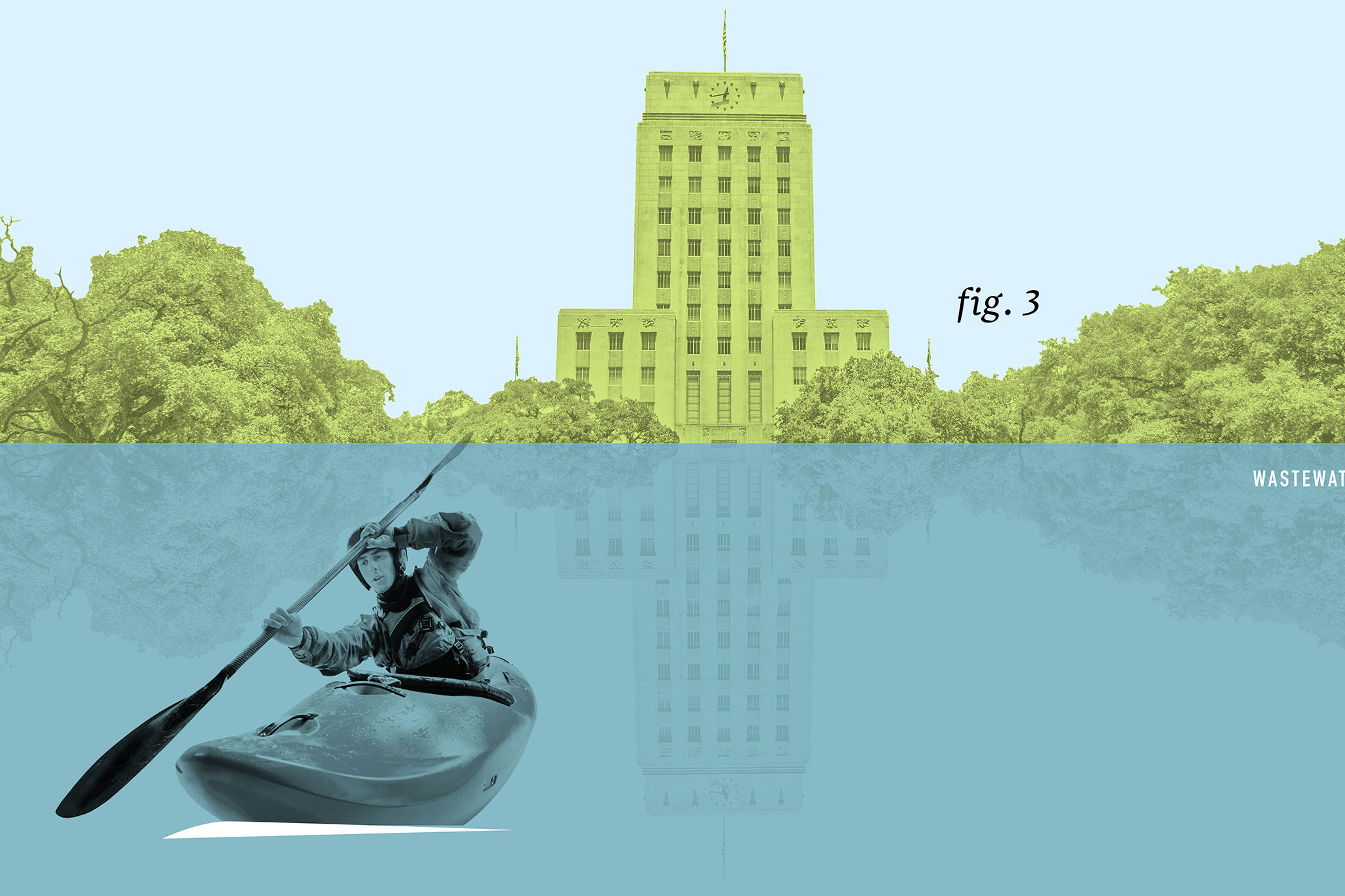

For the city, it was certainly a step back— although things could have been worse. In March, after a brief standoff, the Houston City Council struck a new two-year deal with Waste Management, one the financially strapped city was able to afford. Our curbside recycling program, Houstonians were relieved to hear, wouldn’t be nixed entirely. But glass, the priciest and heaviest of all recyclables, would be eliminated.

No longer could we place our wine bottles and pickle jars in green bins for pickup, something we’d grown to take for granted. Many were frustrated by the change, which felt like an unwanted step backward. Waste Management gave the city four months before ceasing glass pickup, a grace period now coming to an end. Starting this month, Houstonians who want to continue recycling glass will have to transport it to recycling stations themselves, although in certain zip codes, there’s another option.

In April, David Krohn, 28, and his girlfriend’s 8-year-old brother, Tristan Berlanga, decided to start a small recycling-pickup business, Hauling Glass, to pick up the city’s slack. For a $10 monthly fee, they now collect glass every other week for residents in three Heights-area zip codes, carrying it away in their 1977 Jeep Wagoneer to a downtown warehouse for pickup by another company. So far, 220 houses have signed up, and hundreds more have requested pickup in additional zip codes.

“Originally, we thought it’d just be an hour to pick up every other week after I got off work and he’s off from school,” Krohn says. “But we’ve had a crazy amount of people signing up already, and we have a ton of demand in other zip codes. So right now we’re trying to figure out how to expand as quickly as possible.”

It was a heartwarming coda to a disheartening turn of events. After all, everyone loves a tale of an 8-year-old entrepreneur. But more than that, citizens stepping in to get something done when local government could or would not— that’s pure Houston. This is the city whose own Ship Channel exists only because Jesse Jones helped match the federal government’s funds to build the thing. The project was one of the city’s first public-private partnerships, and a model Houston’s followed ever since.

In late May, with a looming pension crisis pushing down the city’s credit rating, Mayor Sylvester Turner passed his first budget, closing a potential $160 million shortfall by cutting many city departments by 5 to 7 percent and spending $82 million less in the coming year.

Private contracts—which are typically able to provide services more cheaply and efficiently than a city government can—have long been a part of the city’s arsenal in cost-cutting. Much of Houston’s infrastructure has been built by private entities, from its roads to its public buildings and universities. Indeed, Waste Management itself is privately held.

Bill Fulton, the director of the Kinder Institute for Urban Research at Rice University, says it’s likely contracting will increase as the city’s budget gets tighter and tighter. “We’re going to see two things—a continuing reluctance to raise taxes, and legacy costs of the pension systems continuing to go up for quite a while,” he says. “In order to accommodate that cost, cities like Houston are going to have to find efficiencies, and contracting is one way they’re likely to do that.”

But the model only works if the contractor’s making money. Any profits associated with recycling—and, increasingly, there are no profits at recycling facilities across the nation—are directly tied to the volatile commodities market for things like glass and aluminum. And because of the falling price of glass, the newly renegotiated contract between Houston and Waste Management was going to have to accommodate that, says Steven Craig, an economics professor at the University of Houston. “Recycling has to be subsidized to work,” Craig says, “and private business can’t quite make it work.”

Craig’s following along to see if Hauling Glass will be able to make a profit on their $10 monthly fee. He thinks the city is likely watching, too. “Having a private recycling business is an interesting mechanism for the city to see how important that service is to residents,”he says.

As the cash-strapped city searches for savings, there is, of course, another factor at play: philanthropy. In Houston, private donors—foundations, corporations, families—have long provided services and amenities that people want, but the city government can’t quite afford (think the new Buffalo Bayou Park, and downtown centerpiece Discovery Green, both of which were heavily financed by the Kinder family). “Parks, libraries and other outward-facing services that people can relate to and that are important to people are going to be supported more and more by private donors,” Fulton says.

From an economics standpoint, Craig says the reliance on private business and charitable donors will continue as long as city services fall short of residents’ wants. “In some sense, if you want to insist on a small government, you are counting on philanthropy to make up some of the difference,” Craig says, “and in Houston, people tend to be pretty generous.”

He even includes Hauling Glass in his view of philanthropy—not from the standpoint of the business, which will hopefully turn a profit, but from its patrons. After all, they could always throw their wine bottles and pickle jars out with the trash. “Customers are signing up to get their glass collected. That’s philanthropy,” he says. “They’re volunteering to pay because they believe in recycling.”