Pro Bono: Meet the Attorneys Helping Houstonians Navigate the Travel Ban

Monica Uddin met Usama Allami on the morning of Sunday, January 29, at the international terminal of George Bush Intercontinental Airport. He looked hesitant, anxious. “Usama was standing outside the area where the lawyers were,” she says, “trying to catch my eye.”

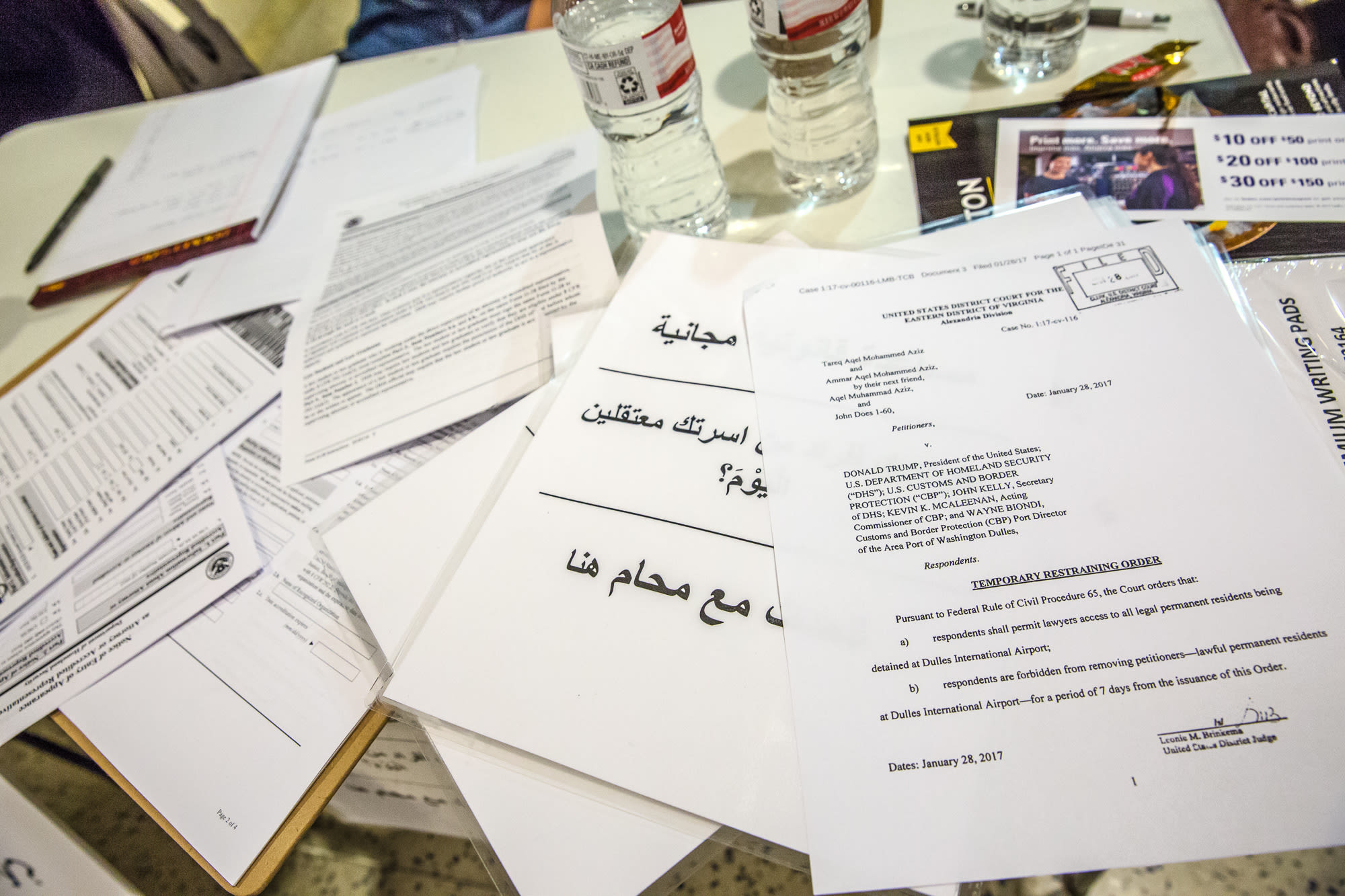

For the 24 hours preceding their meeting, a slew of local attorneys had traded shifts outside a Terminal E Starbucks, near baggage claim. The attorneys were offering pro bono legal assistance for traveling Houstonians caught flat-footed by President Trumps’s hasty executive order, which temporarily banned travel from seven Muslim-majority countries.

Several days later, on February 3, a federal judge in Seattle would impose a temporary nationwide halt; Trump, in turn, would ridicule the judge, a well-respected Republican appointee. But that was all to come.

Amid the initial chaos caused by the order, a call to action on Facebook had begotten Lawyers for Good Governance, a listserv on which attorneys—immigration specialists or otherwise—began coordinating resources and schedules. Their placard was white and straightforward: “Is your family member being detained today? TALK TO AN ATTORNEY HERE.”

One day, according to business lawyer Robert Icsezen volunteered, some 20 lawyers had turned up. “So they had too many people," he says. "There are a ton of lawyers willing to help.”

Uddin was one of them. An associate at AZA and the proud daughter of Muslim immigrants from Bangladesh, she’d watched the news of Trump’s action horrified. When she got herself to Bush, expecting havoc and confusion, Allami was one of the first people she met.

A thirty-something Iraqi native with a trim beard and soulful eyes, Allami had worked as an interpreter during the Iraq War, helping both the U.S. military and U.S.-based military contractors. Five years after putting in his initial application, in 2011, he was finally granted a special visa from the State Department recognizing his service. But thanks to Trump’s maneuver, his wife and 7-year-old daughter were potentially caught in limbo.

Which is why, two days before they were scheduled to fly back to Houston from Iraq, where they'd been visiting family, a worried Allami showed up at the airport and enlisted Uddin's help.

The pair was scheduled to arrive in Houston that Tuesday, January 31. His wife, he told Uddin, was seven months pregnant. Neither she nor their daughter spoke much English. Would border patrol let them back in the country? How could he prepare?

Uddin listened to Allami’s story, took down his information. Like all the attorneys navigating this murky legal water, she tried to assuage his worries, difficult as it was. At the time, the Department of Homeland Security and the White House were still issuing contradictory information, particularly as it related to the status of green card holders. “He was really concerned,” she says, “as any responsible husband and father in that situation would be.”

Allami drove back home. The next day, Uddin dialed him up, telling him that while his family might undergo a few hours of extended screening, she didn’t think they’d run into any roadblocks.

Finally, on Tuesday afternoon, around 2:30 p.m., Allami returned to Terminal E, bearing a bouquet of flowers and a plush white teddy bear. His family’s flight was set to land at 3 p.m. Cell phones are prohibited while travelers circulate through the customs process, so all Allami could do was wait as patiently as possible on the other end. “He couldn't help himself,” Uddin says. “I kept telling him it would take hours, maybe he should sit down for a few minutes. He was standing up at the rail the whole time.”

Three hours later, his wife strolled through the sliding glass doors, pushing a giant cart of luggage, smile wide. Despite all the initial confusion and anxiety, they’d cleared border patrol without incident. His pigtailed daughter hugged her new teddy bear nearly as hard as her relieved dad.

People at the airport were generally supportive of the lawyers’ efforts, says Ed Duffy, another legal volunteer. And Houston didn’t experience a rash of detentions like airports in New York and Dallas.

Still, the need for clarification isn’t diminishing. Even this past weekend, folks with trips booked months away, or with family in Muslim-majority countries not included in the first draft of the ban (Pakistan, Afghanistan), were still dropping by the makeshift clinic seeking counsel.

“There will definitely be uncertainty for a lot of people going forward,” Duffy says. “That much is clear.”