Pride and Protests: Remembering the Night Anita Bryant Came to Town

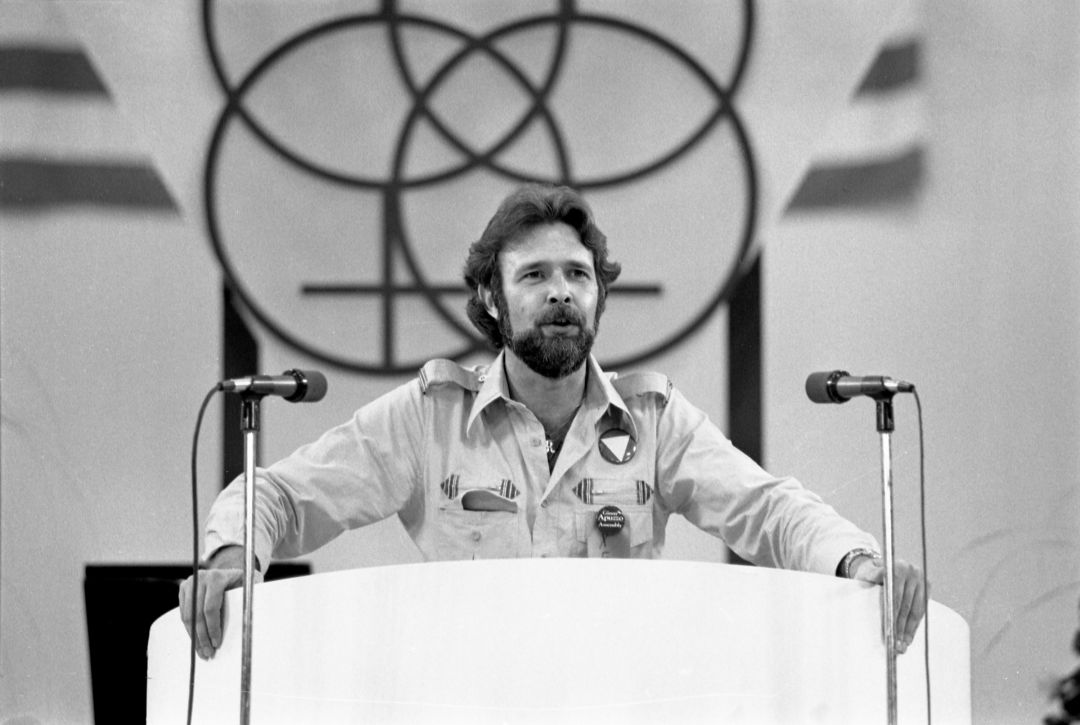

Ray Hill speaks at Town Meeting I in 1978.

In 2015, Houston’s annual Pride Parade moved from its original Montrose streets to a route through downtown and past City Hall. To some, it was an affront on par with the end of the annual Westheimer Street Festival in 1999 or the remodeling of Disco Kroger in 2011, signaling the end of Montrose’s legendary “gayborhood” status.

But, in fact, it was a kind of coming home. A monumental event took place in front of City Hall 40 years ago, on June 16, 1977, without which there would be no Pride Parade as we know it. It was a vigorous protest, the size of which no one had expected, not even its own organizers, against beauty-queen-turned-singer-turned-anti-gay-activist Anita Bryant. It was an important day for Houston’s nascent LBGT community, and one that changed the course of Houston gay history forever.

“It was such an enormously significant event, because up until that point, the words ‘gay community’ meant the part of town where the gay bars were,” explains Ray Hill. “And all of that changed in 24 hours because of Anita Bryant.”

Hill is one of the last men left from those heady days—which suddenly once again feel familiar—when civil rights and anti-war protests drew thousands of hopeful Americans, eager to enact change from the streets. The captivating Hill, now 76 and still residing in Montrose, retains the same towering height and booming yet mellifluous Texas drawl that made him into a natural leader for Houston’s LGBT movement four decades ago.

In the mid-1970s, despite traction made elsewhere in the nation, Houston’s gay community was divided into factions, including the Gay Liberation Front, the Gay Activists Alliance, and the Gay Political Coalition, among others—if they were organized at all. “They thought that the gay-rights movement was having cocktail pity parties where everybody drinks and gets drunk and feels sorry for themselves because of their lot in life,” chuckles Hill. “I was thinking, In the streets! Storm the Bastille!”

At the time, Hill was already unique among his peers, a former high school quarterback and ex-con who’d been sentenced to 160 years for tax evasion in 1970, and then been paroled on appeal in ’75. He was hosting a popular gay-rights radio show on KPFT, and attempting to once again organize his community. His own short-lived attempt at an LGBT coalition, the Promethean Society, had fallen apart when Hill went to prison (an experience that, in 1980, he would parlay into the popular and long-running KPFT broadcast The Prison Show). He became the loudest voice and rowdiest rabble-rouser in Houston’s gay community.

Anita Bryant performs at the Hyatt Regency.

Elsewhere, more progress already had been made. The famous Stonewall riots, which took place after the umpteenth police raid of a Greenwich Village gay bar on June 28, 1969, spurred revolutions in coastal cities such as New York City, Los Angeles and San Francisco, all of which held their first Pride parades the following year, in 1970. Houston held its first Pride Parade in 1976, but it was sparsely attended. There simply wasn’t the sort of critical mass necessary to sustain it—we didn’t have a catalytic event like the Stonewall riots, nor a charismatic political leader like Harvey Milk, San Francisco’s “Mayor of Castro Street.”

Along with Gary Van Ooteghem, the brilliant Harris County comptroller who was fired in 1975 after publicly advocating for gay rights, Hill found a catalyst for change in an impending visit from Anita Bryant.

By 1977, Bryant was better known for her anti-gay activism than her singing. Of her four Top 40 hits in the mid-century, the highest chart-topper was “Paper Roses,” which reached No. 5 on the charts in 1960. Since that time, the former Miss Oklahoma had become the face of the Florida Orange Juice and the Save Our Children campaigns, the latter of which was founded to protect youth from corrupting influences—Bryant boasted she would “lead such a crusade to stop [gay activism] as this country has not seen before.” When Hill found out she’d been invited to Houston to perform at the annual Texas State Bar Association convention, he and Van Ooteghem took their chance to fight back.

At a meeting held in Van Ooteghem’s living room, a few dozen activists planned a small protest to be held outside the Hyatt Regency hotel on the night of Bryant’s performance inside. With less than a month to plan it, no one imagined they’d get a turnout any larger than the 400 people who’d marched in the previous year’s Pride Parade. “And I said, if we get 500 people that’s more than anyone else has ever gotten,” Hill recalls, adding: “Houston’s not a demonstration town.”

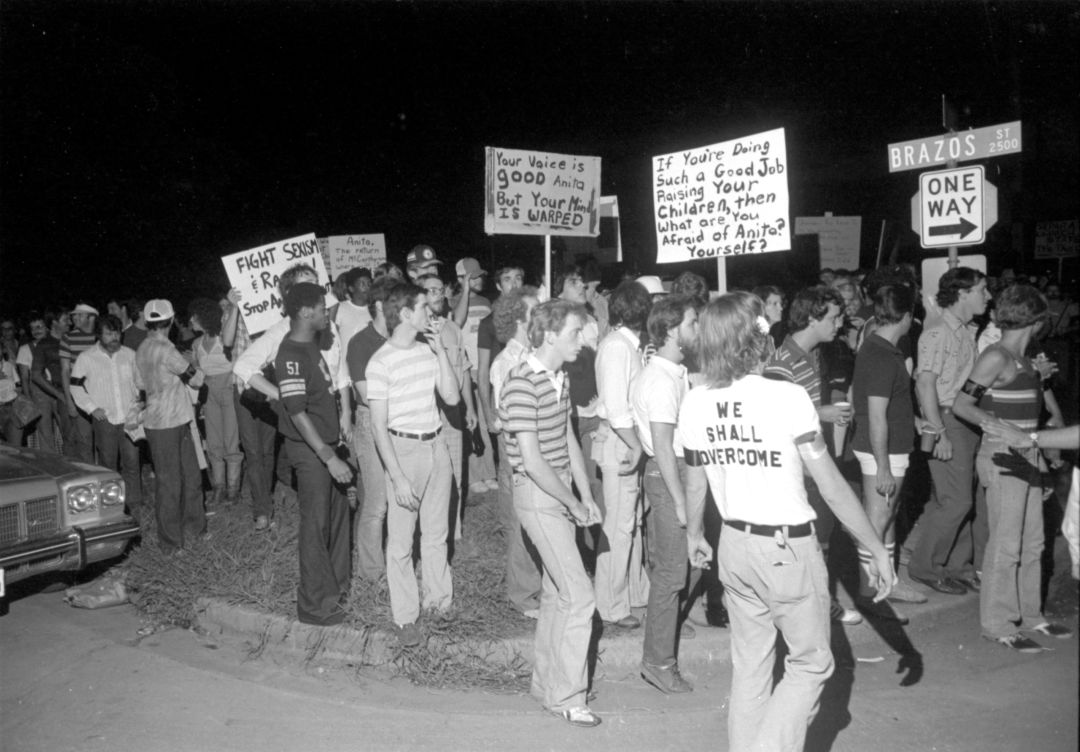

Gay rights activists march down Brazos toward downtown in 1977.

To their surprise, over 10,000 supporters turned out that evening—more than any other protest in Houston’s history until that point. They chanted in front of the Hyatt Regency and City Hall, three blocks away; they drove in from Dallas, Austin and San Antonio; they showed up with drums and flowers; they wore hand-lettered shirts that read “We Shall Overcome” while LGBT-allied ministers held signs that read “The gospel of Jesus Christ, YES!! The gospel of Anita Bryant, NO!!”

The unexpectedly massive event drew national attention, especially when Hill, on a live ABC radio broadcast, urged LGBT allies to boycott Bryant’s OJ backers: “Texas makes great orange juice; Arizona’s got good orange juice; California may have the best orange juice, but Texans don’t say that. Just make damn sure you don’t drink anything that says Florida orange juice!”

By 1980, Bryant had been fired as the spokesperson for Florida Orange Juice following a protracted national boycott, and Save Our Children had perished along with her career. Meanwhile, Houston’s gay community flourished—certainly not the intended effect of Bryant’s passionate campaign against anti-discrimination ordinances and gay adoptions, but a welcome one.

Leaving the protest that June night in 1977, Hill knew a massive shift in consciousness had taken place. “On my way back to my car,” he recalls, “I passed couples that had been together for decades but would never, never, never show affection, who were arm in arm.” And he knew that now was the time to push for still more movement forward.

“I realized that the terms changed. We had become an actual community of people with common goals and aspirations. But we didn’t have institutions to sustain us; we had bars. Now, the American Revolution was planned in taverns,” chuckles Hill, “but our bars were dark, they were loud, they were crowded; they were designed for cruising, not organizing.”

“So on my way back to my car, I conceptualized Houston Town Meeting I, which is what we did for Pride Week 1978. We asked for and were denied, then fought for and won, the Astro Arena, whereupon 2,400 gay people attended, listened to motions and took votes. It was the largest plenary session in the history of the gay movement anywhere.”

During that one meeting, Houston’s gay community outlined their concerns over everything from job security and healthcare to police brutality, while also pouring the foundations for the Montrose Counseling Center, the Montrose Activity Center, the Gay and Lesbian Switchboard, the Hispanic Caucus, and the Montrose Sports Association.

“What I realized we needed and didn’t have in ’77 was to be built in ’78,” says Hill, whose recently won clout led him to organize the National March on Washington for Lesbian and Gay Rights with Harvey Milk, before Milk was assassinated in November 1978. The march in D.C., which eventually took place on October 14, 1979, was the first of its kind, drawing an estimated 125,000 protestors to demand civil rights for the LGBT population at a national level. Back home, Hill earned the nickname “Father of the Houston Gay Movement,” which he wears with—pardon the pun—pride.

“All this is a continuum,” he says. “If it had not been for Anita Bryant, there would not have been Town Meeting I. Without Town Meeting I, there would not be the Montrose Center, Legacy Health Services—all of those things were organized at Town Meeting I.” He breaks into a grin, laughing: “Lesbian softball was organized there—I mean, talk about an institution!”

Houston’s Pride Week 2017 runs June 18–25, with the parade taking place noon–7 p.m. on Saturday, June 24.