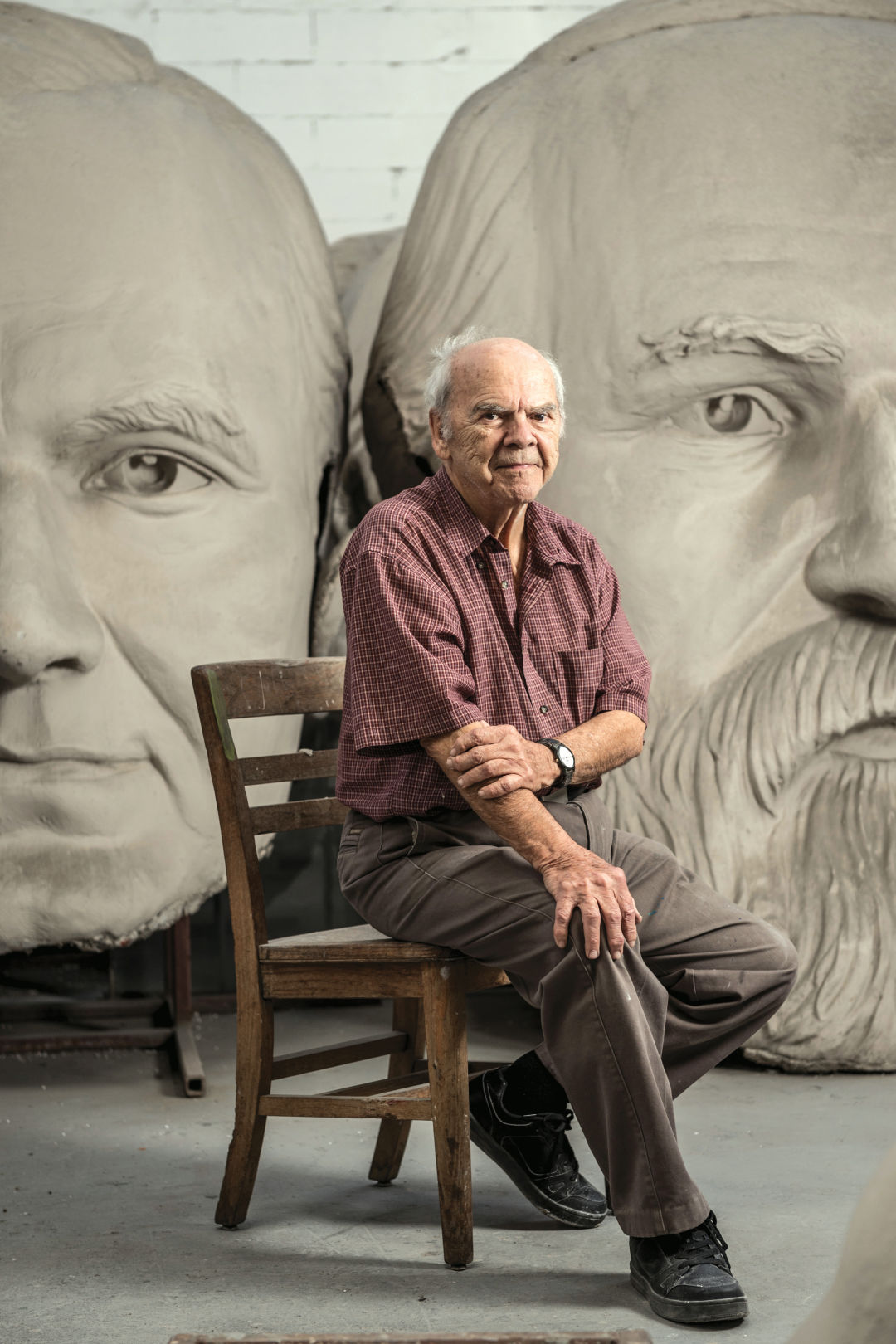

David Adickes Is Larger Than Life

Image: Michael Starghill

When Houston legend David Adickes turned 90 last January, friends began to subtly and not-so-subtly suggest that he retire. “I told ’em, ‘I checked my tires, and I still have about 30,000 miles left. But I have some forklifts that need to be re-tired,’” he laughs, shaking his head as he thinks back to the heavy machinery he’s used to create his enormous statues. “And at my party, not one person bought me a forklift tire. They bought me wine.”

It’s hard to say which Adickes artwork is most iconic. There’s the one that started it all, his 67-foot, cement-and-steel statue of Sam Houston, which stands proudly off I-45 in Adickes’s hometown of Huntsville; his 44 gigantic heads depicting our U.S. presidents (he hasn’t gotten around to Trump); his 36-foot Beatles at 8th Wonder Brewery; his giant cello downtown; his We Love Houston sign; his Mount Rush Hour. While the critics love to hate these works, they’ve been met with a kind of quizzical adoration from Houstonians; today, it’s hard to imagine the local landscape without them.

And now, despite the ever-energetic artist’s reluctance to retire, he’s begun to realize he needs to scale back. In two years, his studio on Nance Street is set to be demolished as part of the expansion and rerouting of I-45 downtown. After that, he’s decided, he’ll no longer make his larger-than-life sculptures, although he’ll continue his prolific painting practice at his nearby home.

Meeting Adickes at his studio, we’re surprised to learn his age. Standing proudly at 5 feet 6 inches tall, he’s positively spry—as he jokes and winks, he gives the impression of bouncing around, even though he’s sitting still as he shares his life story.

When asked how he got started as an artist, Adickes begins, “This is the story of how ten pounds of bananas saved my life.” After graduating high school in Huntsville in 1943, as World War II was nearing its end, Adickes wanted to join the V-5 program, which trained Navy pilots.

“The requirements were, you had to be five-six, which I was, and weigh 115 pounds, which I didn’t—I weighed 105 pounds. A squirt!” he says. A friend suggested he eat 10 pounds of bananas for the weigh-in, which, instead of securing him a spot in the program, landed him in the infirmary with a terrible stomachache.

Instead, Adickes ended up in the Army Air Corps doing paperwork on large transport planes, which carried much-needed supplies to Europe and shipped soldiers back from Paris after the war. It was there, in the cafés and museums of Paris, that Adickes developed his love for art. “I saw Paris for the first time as a 19-year-old kid,” he muses. “How are you gonna keep him down on the farm after that?”

Adickes studied art in the City of Light, then spent some years abroad before making his way back to Houston during the swinging ’60s. On New Year's Eve in 1966, on a trip to San Francisco to see Big Brother and the Holding Company at the Fillmore Auditorium, he found himself captivated by the swirling psychedelic images projected onto the walls.

“I was so taken with the projections that I climbed up and stood behind and watched the guys doing it, so I could see how it was done,” he remembers. “It was the overhead projectors that you used in school, but didn’t exist when I was in school. The whole experience was so ... captivating.”

Back in Houston, he tracked down some projectors and leased the top floor of the old Sunset Coffee Building on Allen’s Landing. He opened a club, christened it Love Street Circus and Feelgood Machine—so ’60s!—and projected his photos and images on the club’s walls. The psychedelic evenings that took place there were called “happenings,” and there may have been drugs involved for some club patrons. But for Adickes, who never even smoked a cigarette, it was all about the art. He later sold the club, which closed its doors in 1970.

So how did Adickes get from a trippy nightclub to gigantic presidents’ heads? There were things in between, but Adickes loves to explain his many wild creative pursuits this way: “I have a disease,” he says. “It’s called Biticus Chewicus.” He winks, or maybe just gives the impression of winking. “I bite off more than I can chew. I get excited about new projects all the time.”

Adickes created his famous Huntsville statue, dedicated in 1994, as part of celebrations for Sam Houston’s 200th birthday. He remembers pitching his idea at a planning meeting, and jaws around the room just dropping. The statue, built in 10-foot sections with steel “bones,” took three years to erect. “It was so fun doing that big head, looking right into his eyes,” Adickes says. It was after that project that he visited Mount Rushmore and got the idea for the presidents’ heads. He’s now done three sets, actually, and is looking for a home for his Nance Street copies before the studio is demolished.

Even though Adickes acknowledges that he’s now in his “closing-down-shop period,” willing his artwork to his daughter and twin granddaughters—and completing what might be his final large sculpture, another Sam Houston, this one on horseback, for a new traffic circle in Baytown—he’s not quite ready to give up the hijinks yet.

He explains an idea he had for his 90th birthday last year. “Picture this: the Astrodome,” he begins, raising his arms to set the scene. “A big 9-0 sculpture hanging from the ceiling, and 90 beautiful girls with candles on their heads. I go around and blow out each one.” That didn't happen, unfortunately, but there's always his 100th.

Again, he winks.