The Stories of a City: HIV/AIDS in Houston

Tori Williams helped care for AIDS patients in Montrose from the early days of the crisis.

Image: Todd Spoth

Almost two dozen portraits line the wall of a conference room at the Ryan White Planning Council. Tori Williams stares up at it, taking in each face. “These are the people who’ve passed away who’ve been volunteers here,” she says. “And I know there are many that we don’t have on that wall, because as they started to get sick, sometimes they didn’t tell us.”

Since 1998, Williams has had various roles at Ryan White, where today she’s director. In that capacity, she leads efforts to determine how best to spend federal funding—currently about $28 million per year—for Houstonians living with HIV. But she’s been assisting the local population affected by HIV/AIDS, in one capacity or another, since the mid-’80s. And after decades in the field, she’s become a kind of living repository of the history of the disease in Houston.

Because of that, in recent years, she’s taken on another role, too: the role of remembering. With Harris County head archivist Sarah Canby Jackson, Williams is leading an effort to preserve the stories of those who were there as AIDS ravaged an entire community, and who survived to share them.

It was Jackson who found Williams, in 2015, after trying to research the history of AIDS in Houston and realizing that, unlike other cities, we had preserved almost no documentation on the local epidemic. “I was shocked to find no reference materials,” Jackson says. “I expected to find at least a master’s thesis and oral history collection at either the University of Houston or Rice University dealing with this subject.”

After a conversation with Jackson, Williams put together a timeline of key moments in local history. “It took me three weeks to pull all these pieces together,” Williams says, “and I just cried and cried and cried for three weeks. It made me realize how much I hadn’t processed, and I knew I wasn’t the only one.”

It was with that realization that The Oral History Project (The oH Project) was born. Williams started a list of names of Houstonians to interview, which has continued to grow. The plan is to gather at least 100 stories, including Williams’s own, by 2020. The project will span the period starting in the early ’80s, at the beginning of the outbreak, and carry through the mid-’90s, when new lifesaving drugs were approved for use.

The interviews—a few dozen have been done so far—are being conducted by a team of six people, who are speaking to a wide range of Houstonians affected by the disease: longtime HIV survivors; doctors who treated patients before they knew what the disease was; transgender women, whose local community was devastated early by the disease; people with hemophilia, who were infected before the blood-bank system was cleaned up and regulated; African American men and women, whose community continues to be disproportionately affected by the virus; and so many others.

As the interviews are completed, they’re archived online and at the Woodson Research Center at Rice University, where everyone who lives here can read and listen to them, and learn about the city’s HIV/AIDS history. Ahead of the project’s completion, Williams and two other Houstonians interviewed for the project agreed to sit down with Houstonia and share their memories.

These three stories, along with at least 97 others, will be part of a project predicated on hope: the hope for greater understanding, the hope that those lost will be remembered, the hope that these memories can provide a fuller picture of the history of the HIV/AIDS crisis in Houston. Recording this history has become even more important as the United States continues to move away from leading efforts to stem the tide of what became a global epidemic. “I just really believe it’s important for people to understand what happened,” says Williams, “especially for those who’ve never known life without it.”

Carmon Brian Keever says Montrose was a place where people like him were free to be themselves.

Image: Todd Spoth

In the early ’80s, a positive HIV test was a death sentence. “People were being diagnosed, and they were dying within six months of diagnosis,” remembers Williams. “That fast. Sometimes a little longer, but sometimes shorter. That’s how bad it was. It just hit them, boom.”

It was during this period that Carmon Brian Keever, almost 30, moved to Houston from North Carolina. He landed in Montrose, where the gay scene was white-hot and people like him were liberated, free to be themselves.

“There were maybe 40 bars here in the early ’80s. … There were drag bars, leather bars, dyke bars—you name it, if there was a type, there was a bar for it,” Keever laughs. “You knew holding your other half’s arm was probably not a good thing to do in La Porte, or Pasadena, or places like that. But down here in Montrose, you could get away with it.”

Keever cobbled together a living by working in a florist shop and entertaining in drag under his stage name, Damita Jo. “I like to say I was a professional homosexual,” he jokes today.

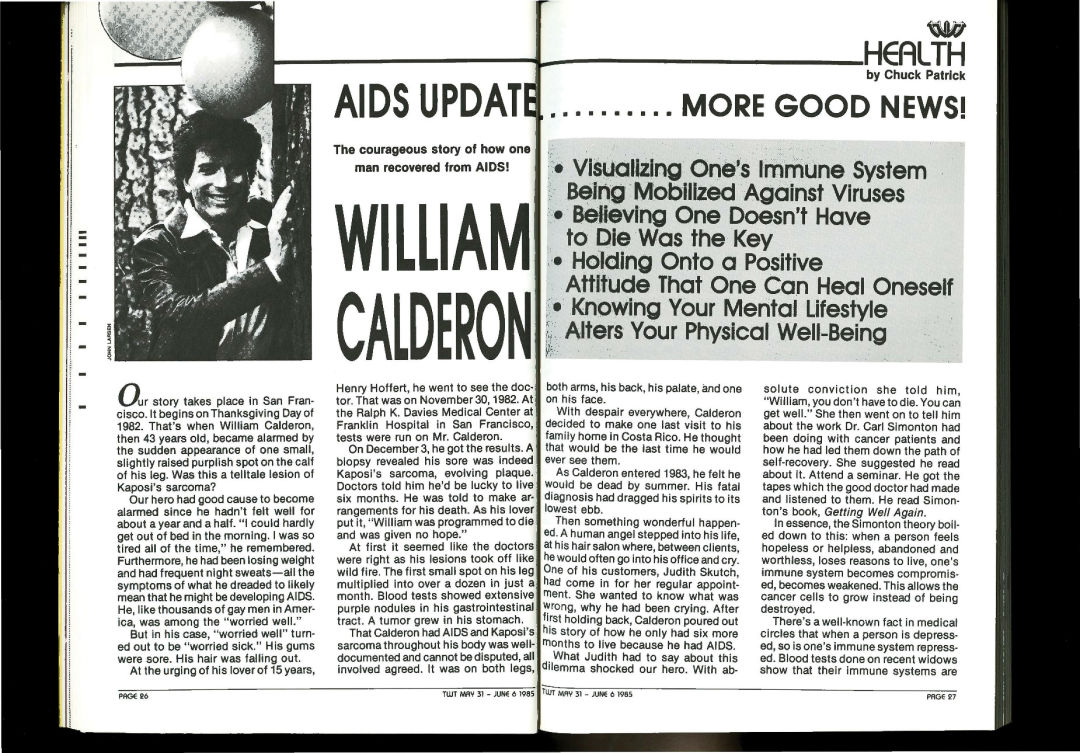

But his nirvana was short-lived. Soon, Keever began to hear rumors about people in the gay communities in New York and San Francisco getting sick. This Week in Texas, a gay magazine based in Houston where Keever worked for more than a decade, ran a small blurb in July 1981 about a rare form of cancer called Kaposi’s sarcoma, which was affecting gay men disproportionately.

A couple of months later, the magazine ran a blurb about pneumocystis pneumonia, another disease popping up more and more in the gay community. Then, in February 1982, it ran a feature by a doctor at MD Anderson, called “Gay Disease? Kaposi’s sarcoma and other opportunistic infections.”

Doctors and scientists soon realized that these cases were not separate; they scrambled to get a full picture of what the disease was and how to treat it, as more and more gay men became fatally ill at an alarming rate.

It was that same year that the AIDS Foundation Houston was formed to provide resources for people living with AIDS, and the LGBTQ community in Houston began rallying together, raising money to treat the sick and forming networks to care for them. Keever held drag-performance fundraisers, and spent his free time at hospitals that were accepting patients.

“We were going, ‘We need to take care of these people; no one else is gonna do it. We have to go out and raise money one dollar at a time if we have to,’” he remembers.

This Week in Texas began to fill up with obituaries as more and more people in the community were lost to the disease. Some years passed, and then, after Keever suffered a serious bout of the flu, his friends urged him to get tested. His test came back positive for HIV.

“I got diagnosed in ’86,” Keever says, “and they said, ‘Get your things in order, you’ll probably be gone by ’88.’”

By 1986, when Williams moved back to Houston after a stint away, the AIDS breakout both here and in the rest of the country was well-known. “It was like living in a nightmare,” remembers Williams, “because someone would be completely fine, and then the next day they’d have a terrible flu, and they wouldn’t get better and wouldn’t get better.

“And everybody knew, take them to Ben Taub, and take a blanket with you. … And take toilet paper. And stay with them as long as you can. But sometimes they wouldn’t get seen for like a day and a half. Ben Taub was really backed up all the time,” she says.

Williams is a lesbian, and, like Keever, in the ’80s called Montrose home. When the disease took hold, she and her friends helped care for the sick in the city’s gay and transgender communities. At the time, no one knew for sure how AIDS was contracted. Even many in the medical professions were scared to work closely with the patients who were shuffling into overcrowded hospitals, incredibly sick with a host of different ailments.

“See, even the people who worked at the hospitals, they didn’t want to go into the room,” Williams says. “They didn’t want to take a tray of food into somebody. They certainly weren’t changing the sheets, or bathing somebody.”

Williams was hired on at the United Way as an AIDS consultant in 1987, and in 1988 she moved to the AIDS Interfaith Council, where she organized teams of churchgoers to care for needy AIDS patients.

“These little old ladies would have these big pocketbooks and they would have a bar of Dial soap in a plastic bag, and they would go and see their dear friend, Tommy or John or whomever, and afterward, they’d go in the restroom and they’d wash with Dial soap all over everywhere, and then they’d go home and make dinner for their families,” she says.

The crisis, and the fear it engendered, reverberated through local politics. In the early ’80s, Houston’s gay community started gaining clout, with the city’s GLBT Political Caucus helping to elect Mayor Kathy Whitmire in 1981. But by the mid-’80s, the tide had turned. An anti-discrimination ordinance that would have protected gay and lesbian people in the workplace failed terribly at the polls, and with the fear of AIDS reaching fever pitch, politicians began distancing themselves from the gay community.

In 1985, Whitmire ran for reelection against Louie Welch, a former five-term mayor who was trying to stage a comeback. Having opposed the anti-discrimination ordinance as the head of the Houston Chamber of Commerce, Welch was endorsed by a group called the Straight Slate.

Welch used the fear of AIDS throughout his campaign but, two weeks before the election, made a gaffe that revealed the depth of his hatred. A reporter asked him what he thought should be done about the AIDS crisis locally, and, not knowing the microphone was on, Welch replied, “Shoot the queers.” He went on to lose the election, with Whitmire earning nearly 60 percent of the vote.

In 1988, Williams, still with the United Way, went to a community meeting hosted by the Houston–Harris County Task Force on AIDS. “It was jam-packed when I walked in,” she remembers. “But there was a guy who had Kaposi’s, and you could see the spots on his arms and his face, so he was the person in the room who was clearly HIV-positive. And even though there was standing-room only, he was in a chair. And no one sat on his left side, and no one was sitting on his right. There were two empty chairs in that room, and they were on each side of him.”

Recounting the memory, Williams becomes visibly upset. “These were people who were educated about HIV, this was the task force on HIV. And they still wouldn’t sit next to him,” she says. “I went up and said, ‘Do you mind if I sit next to you?’ And he said no, and I gave him a big hug. And I said, ‘I’m really glad you’re here.’”

Steven Vargas watched in alarm as his stepfather rapidly lost weight from undiagnosed AIDS.

Image: Todd Spoth

By the dawn of the next decade, some began to realize that AIDS wasn’t only affecting gay men. In 1990, Houstonian Steven Vargas, who was openly gay, watched in alarm as his stepfather, a cook in a restaurant, rapidly lost weight. After visits to multiple doctors, the sick man remained undiagnosed. It was Vargas who first suggested his stepfather be tested for HIV.

“They just kind of blew it off and said, ‘Well no, he’s married,’” Vargas remembers. His stepfather, however, had a history of drug use. When he was finally tested, the results were positive.

Vargas’s mother was tested, and the family learned that she too was HIV-positive. Over the next five years, Vargas helped care for his stepfather, who died in 1994, and his mother, who succumbed the following year. “She was a heterosexual Latina, living with HIV,” Vargas says. “In those days, that whole picture of HIV being a gay man’s disease was so prevalent that if a straight woman from the suburbs wanted to get tested, you probably had to convince your doctor to do so.”

Vargas remembers taking his mother to an AIDS support group meeting, where the people living with HIV/AIDS met separately from their caretakers. “I just remember walking in there with my mother, and my mother and I talking about the little switch on us. Here I am as a gay son, supporting a straight mother with HIV, when there were all these straight parents supporting their gay sons with HIV,” he says.

In 1995, when his mother was at the end of her life, Vargas also tested positive for HIV. He was 27 years old. He hid his diagnosis from his family, because he didn’t want to add to their grief. At the time, he was sure his future would look a lot like his mother and stepfather’s—in and out of hospitals, increasingly sick, until his body gave up fighting in a few years’ time.

“My mother’s life, her entire life with HIV wasn’t very long at all; there was no treatment, there were no medications. At the time, in Montrose, if a gay man was diagnosed with HIV, they might be aware of these medications that were coming out. On this side of town, if you were diagnosed with HIV, you still saw it as a death sentence.”

Vargas’s mother passed away without ever learning of her son’s diagnosis. After she died, he went through several years of depression and drug use. “It got to the point—five, six years of all this—I couldn’t even remember the last time I smiled. I couldn’t even remember the feeling of how does it feel to smile?—the physical sensation to have your lips do that.

“I remember standing in front of a mirror trying to get myself to smile, and it was difficult. I remember telling myself, Probably just move your lips up. I remember getting my hands and going like this, pushing the corners of my lips up to kind of create a smile.”

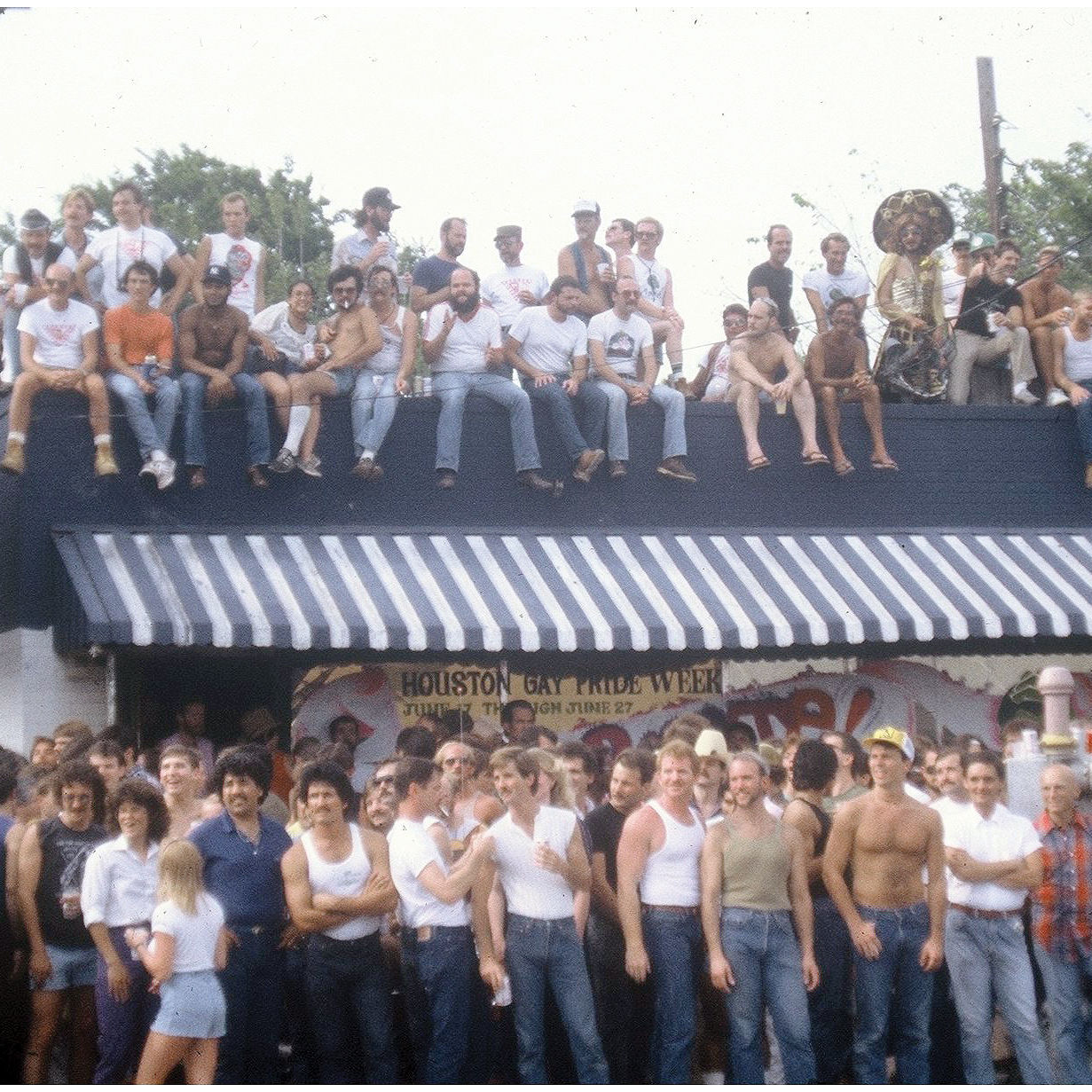

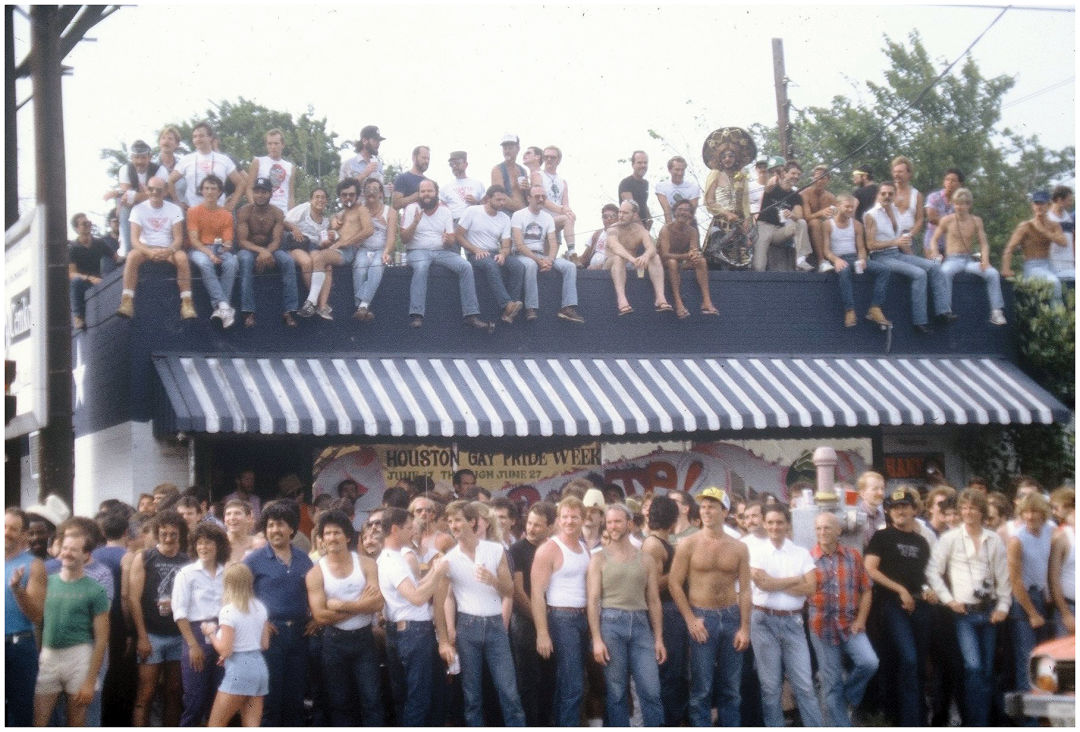

Mary's bar on Westheimer was a place of support and family for the community.

Image: JD Doyle

What ended up turning Vargas’s life around was the same thing that kept Keever fighting: the realization that others like them, who were living with HIV, needed help.

In the mid-’80s, after Keever learned of his diagnosis and was given two years to live, he made a decision. “If I’m gonna go, I might as well go out in a blaze of glory,” he told himself. He became a vocal activist, “demonstrating, yelling, hollering,” as he calls it. In between bouts of illness at local hospitals, he marched on Washington and joined the boards of several local AIDS organizations.

In the late ’80s, Keever took part in a clinical trial for a medication that he says saved his life. He, of course, is one of the lucky ones; only a tiny minority of those who contracted HIV when he did are alive today.

Keever vividly remembers those early years, when he tried to stay busy at all times. “I was in charge of this or this or this, and someone says to me, ‘Why don’t you just stay home?’ And I wouldn’t tell them this, but I look back now and I think I was too scared to just stay home. That if I stayed home, I’d get sick. If I stayed home, I’d worry. And so as long as I kept myself active, busy, and doing something, I wasn’t thinking about it.”

Vargas had an epiphany in a drug-induced haze—he looked in the mirror after a night dancing in the club, and he was smiling. “I knew if I could smile on drugs, I could smile without them,” he says. As he got sober, he thought about something that his mom said to him once after a support group meeting.

“She was almost always one of very few women, and that particular time there were two other women, and I think that’s the most women living with HIV we’d seen there that entire time that I was taking my mother,” he says. “She leaned over and she whispered in my ear, ‘You know there’s more women than this, mijo. There’s going to be so many women with HIV.”

Seven or eight years after his mother had passed away, that memory came flooding back to Vargas as he read an article about the rise of HIV in women. “I remember thinking to myself, Why isn’t anyone doing anything? Just generally. Then I thought more specifically, you know, of people that I knew: Why isn’t...?, Oh wait, they’re gone. And then I started going through folks that I knew that were out there and would do things, and every name that came up, they were no longer with us—they were dead,” he says.

“So that’s when it dawned on me that we need to step up. Those of us that are still around, need to step up and see what we can do to make a difference because the other ones aren’t with us anymore. You can’t let that flag hit the ground.” Vargas now works for the Association for the Advancement of Mexican Americans, administering housing support for people living with HIV, and helping to educate Latinos about protecting themselves from the virus. Vargas’s T-cell count—a marker that helps to gauge the health of his immune system—has been rising steadily with his consistent use of medication; the virus has been undetectable in his body for four years.

Keever works for Legacy, formerly the Montrose Clinic, which started as an STD clinic for gay men in 1978 and has treated people with HIV and AIDS since the earliest days of the crisis. He spends his free time checking up on other people living with HIV, ensuring they’re taking their medications, and staying up-to-date on their doctor’s appointments.

“Someone said, ‘you know, you don’t get paid to do that,’ and I went, ‘And?’” he says. “I’m a social worker without having the degree or any of that, and it helps me and helps them at the same time, because it gives me stuff that I need to do.” Keever’s consistent treatment has led to a healthy T-cell count. His HIV has been undetectable for five years.

A 1985 story from Houston-based gay magazine This Week in Texas shows how AIDS was still a misunderstood disease.

Image: This Week in Texas

As Williams talks about the Oral History Project and delves into her experiences over the past three decades—working with people living with HIV and those who died of AIDS—she tears up more than once. She wipes her eyes at the table in the conference room.

“We’re finding a lot of people cry in their interviews because a lot happened in those years, and in order to keep moving forward you had to sort of shut down. And so at first, a lot of people are afraid to be interviewed in the Oral History Project, because they don’t want to remember that time,” she says.

“But we are far enough away that people are starting to be willing to be interviewed. You’ll find people who worked in AIDS in the old days—it was painful, no matter what you did, it was painful. Some days it’s more on the surface than other days, and sometimes…” she trails off and looks away.

Even those who managed to survive and live long lives with HIV, Williams reflects, are starting to get older. This means that the time to gather these stories is now. “Because there are long-term survivors,” she says, “but every day there are fewer of them.”

The stories are heartbreaking, but Williams hopes they will inspire people, too, to continue to fight for the vulnerable. “This political climate, this is not the first time we’ve isolated people. This is not the first time we’ve used fear to pull people apart and to rally people to dislike. These are not new techniques at all. And we have to look—what did we do in the AIDS community?” she says. “We can do it better, and I hope these transcripts will help people to learn.”