This UH Research Center Is Revolutionizing Archaeology

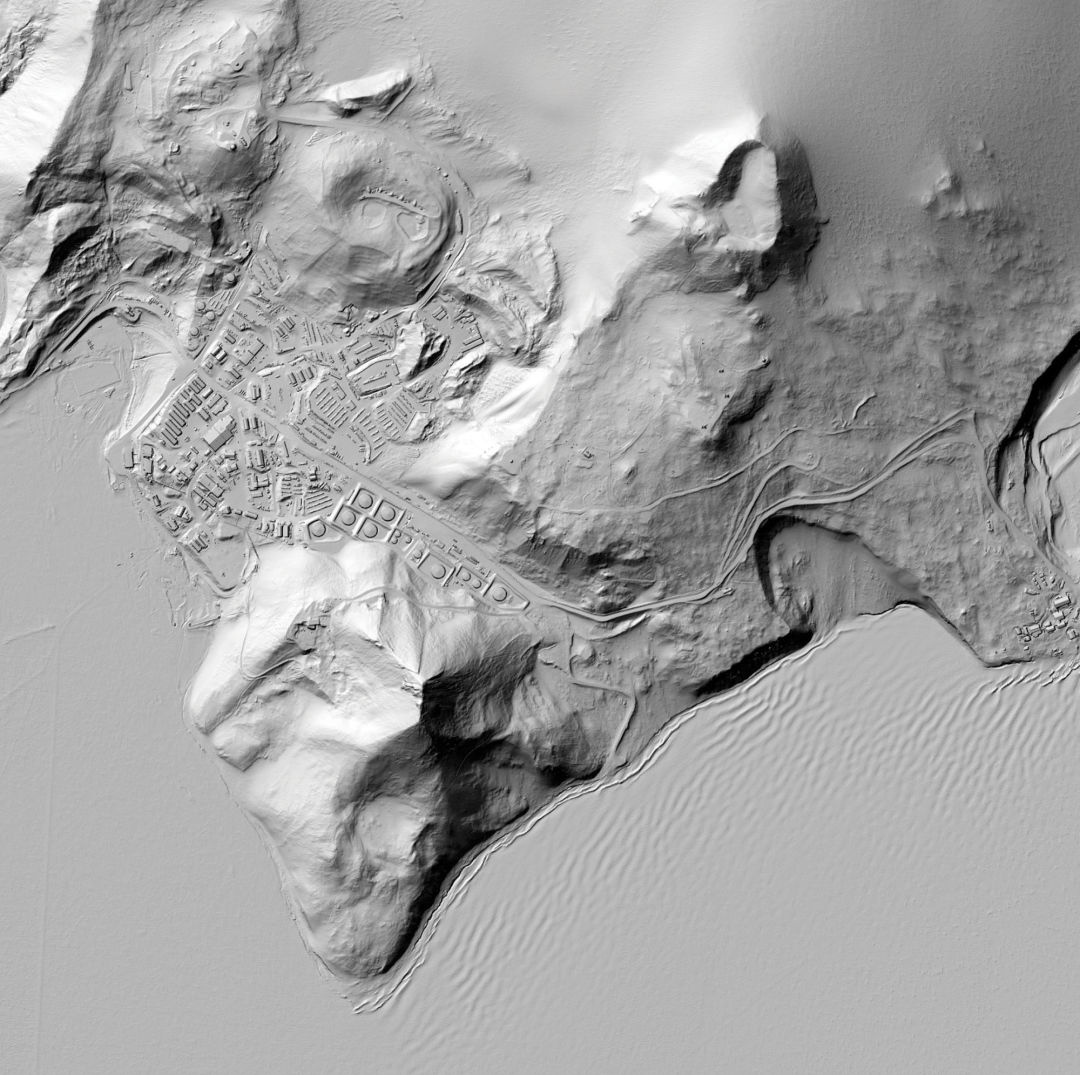

An image of a station in Antarctica mapped by LiDAR

The year was 2012; the place, the Honduran rainforest. A small plane flew overhead, dangling an expensive pulsing laser over the dense, leafy canopy. Within just a few hours, Ramesh Shrestha, director of UH’s National Center for Airborne Laser Mapping, spotted the same thing a colleague had first noticed: a place forgotten for centuries, now visible in the form of a crude rectangular shape scratched into the earth. “Nature doesn’t make rectangles, and yet there it was,” he remembers. “When we removed the trees, it was unmistakable.”

Afterward, the two leaders of the project, a filmmaker and explorer who’d organized that search, who’d been hoping to find the mythic Ciudad Blanca (“White City”), were hailed for discovering the ruins of what they dubbed the City of the Monkey God. The find featured in National Geographic and Outside, a TV documentary, and even a book, The Lost City of the Monkey God, published last year.

Meanwhile, the researchers behind the discovery were barely mentioned, despite the fact that it wouldn’t have happened without them and NCALM—the UH research center that Shrestha founded in partnership with UC-Berkeley, and the only one of its kind in the country employing LiDAR (Light Detection and Ranging) technology to create detailed renderings of the earth. The method, which uses pulsed lasers to measure varying distances to earth, has been called the biggest advance in the field of archeology since the invention of carbon-14 dating.

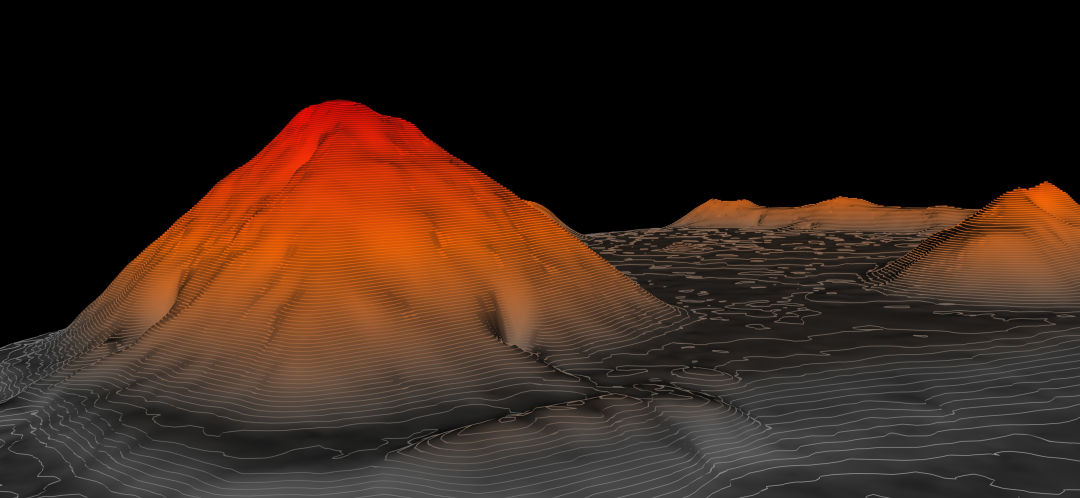

The lack of attention didn’t slow Shrestha’s team down by any means. In February of this year, NCALM surveyed 800 square miles—an expanse one and a half times the size of Los Angeles—of the Maya Biosphere in the Petén region of Guatemala, producing the largest LiDAR data set ever gathered for archeological research. Archeologists found more than 60,000 Mayan structures on the resulting maps, an astounding discovery. In the past, such an effort would have taken decades—if it was possible at all—but the LiDAR system pulled it off in a matter of hours.

Shrestha grew up in a small village in western Nepal that had no school until he was a boy. “I think it is fair to say that I grew up in a different world as a kid. Sometimes I feel I skipped an entire century to be where I am today,” Shrestha says. “Obviously, I couldn’t have dreamed of overseeing NCALM when I was growing up in the village.”

One of the many pyramids hidden in the jungle of Naachtun, Guatemala, seen by NCALM LiDar.

In 1970s-era Nepal only a few people got the chance to attend college abroad, but Shrestha’s test scores won him a spot studying surveying at the University of London. He continued his schooling in the United States, and by 1986, was a civil engineering professor at the University of Florida and a U.S. citizen. “What I have become is only possible in the United States,” he says, “because of the people who helped me come here, and the opportunities this country and its systems provided to people like me.”

Shrestha’s fascination with LiDAR started in the mid-1990s, when he came across an article in a trade magazine describing how a guy had figured out how to harness the technology, invented in the 1960s, for commercial mapmaking. He learned to use a LiDAR scanner and started doing work for various Florida government entities, charging nothing but the cost of the research and the price of the equipment, which he got to keep. “They got updated maps,” he remembers, “and I got the LiDAR machine. It was perfect.”

Soon professors from across the country were approaching him about using the scanner for their own research. By 2003 Shrestha had gotten funding from the National Science Foundation, and six years later, he and his Florida team contributed to their first major archeological breakthrough, when they surveyed a set of Mayan ruins in Belize. Maps revealed that archeologists who’d been exploring the site for more than 25 years had discovered only about 10 percent of it.

In 2010, when a former colleague approached him about moving the center to UH, Shrestha leapt at the chance. UH boosted his funding, created accredited graduate and PhD programs in geosensing systems engineering, and let him hire six other faculty members, doubling the size of his program. “UH wanted the center,” he says. “And it made sense. So much of our work is in Central America and this put us that much closer to it.”

Some archeologists have criticized the use of LiDAR, maintaining it’s a shortcut that does little to help researchers understand what they’re finding, but Shrestha doesn’t lose sleep over that. “There will always be naysayers,” he says, “but I do not worry too much about them, because I know what we did—and are doing—are the right things to do to advance science.”