Weslayan Plaza Could've Been the World's First Mall

Montclair Shopping Center would have been the world's first enclosed mall.

Image: Courtesy of Gruen Associates

Buried beneath the big-box stores of an unassuming West U shopping center are the bones of what could have been the world's first mall. Today it's Weslayan Plaza, home to Randall's, Walgreens, and a defunct OfficeMax. But in 1950 it was poised to radically redefine the 20th-century shopping experience.

Except it never happened.

Years before the Astrodome brought the architecture of mass spectacle to Houston—and decades before The Galleria elevated Houston’s west side to shopping mecca—a Viennese Socialist named Victor Gruen essentially invented the mall. If things had worked out, his visionary plan for the country’s very first fully enclosed (and air-conditioned) mega shopping center would have been plopped down right on the corner of Weslayan and Bissonnet.

The Montclair Shopping Center, as the original, 1950 development was to be called, was an ambitious project by any postwar building standard. Based on a radical design, “194X,” that the Austrian urban planner first presented in a 1943 issue of Architectural Forum, the Montclair project was envisioned as a massive, dumbbell-shaped complex with more than 100 vendors, a supermarket and rooftop restaurant, and two anchor department stores on two adjoining lots from Academy to Law streets along Bissonnet Avenue, with a portion built over an underground section of Weslayan Street.

“The Montclair Center was exceptional because of its scale and the way it sought to integrate with urban infrastructure,” says Stephen Fox, architectural historian and professor at the Rice School of Architecture.

The multi-story structure was to span 10 blocks, while rooftop parking would alleviate street congestion and maximize pedestrian space. Inside, the main hall was to be meticulously landscaped with gardens, waterfalls, and other Edenic elements, all bathed in natural light—a retail paradise. If the concept sounds quaint and almost démodé today, that’s largely because almost every mall built afterward was based on the Montclair model.

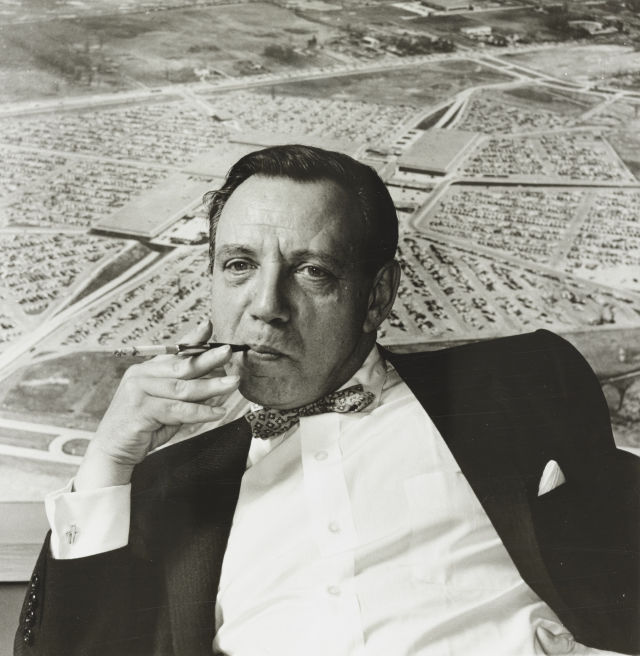

Victor Gruen.

Image: Library of Congress

When Gruen—nee Grünbaum—began planning Montclair, he’d designed only a handful of department stores. Though trained as an architect in 1920s Vienna, he hadn’t practiced much, devoting himself to acting in the city’s leftist cabarets before fleeing to New York following Nazi Germany’s 1938 annexation of Austria. After producing a couple of Broadway shows and doing some commercial design work, he landed in L.A., where the streamline moderne and roadside architecture styles then popular in that city's expanding retail sector captured his imagination. And people loved his projects, developments that were nothing like the downtown shopping districts and automative strip centers that were then the norm in American daily life.

So how did Houston become the target site for his trailblazing concept? By the mid-century mark the Bayou City’s population was booming, and projects like the 1,100-room Shamrock Hotel and the planned McCarthy Center, a massive development near the Texas Med Center being piloted by famed wildcatter Glenn McCarthy, were snagging headlines. Local developer Russell Nix wanted to answer McCarthy’s projects on an equally ambitious scale. Persuaded by Gruen’s unprecedented vision, Nix hired the eccentric Austrian along with Irving Klein, a local architect who’d studied in 1920s Germany and worked with a New York firm that built some of Manhattan’s classic art deco skyscrapers.

(Klein also maintained he got the idea for air-conditioned malls in Houston, according to Fox, but there’s no documentation to back that up, Fox was quick to note.)

Nix promoted Montclair’s progress in trade publications and local papers, claiming major institutional investors and dozens of retail tenants—despite having actually secured few of them. By 1952 Montclair’s sole tenant was a freestanding Weingarten’s grocery store meant to be connected to the larger mall once it was built.

But it never was. Nix talked a good game, but he couldn’t get any lenders to provide the $12 million—then an unheard-of cost for a mere shopping center—and after failing to secure financing, he abandoned the project entirely.

“Houston would have to wait for Ira Berne’s Westbury Square of 1960 and The Galleria of 1969 to make history in the arena of suburban retail architecture,” Fox says.

What became of the Montclair concept? In 1956 Gruen recycled and modified his plan with Minnesota’s Southdale Mall, and the first modern shopping center was built in a Twin Cities suburb. He ultimately published one of the undisputed manuals on retail development, was hailed as the godfather of the American shopping mall, and designed over two dozen malls over the following decades—but none of them were built in Houston.