Beneath the Houston Arboretum Are the Ruins of a World War I Training Camp

Artifacts found at the Houston Arboretum & Nature Center.

Image: Anthony Rathbun

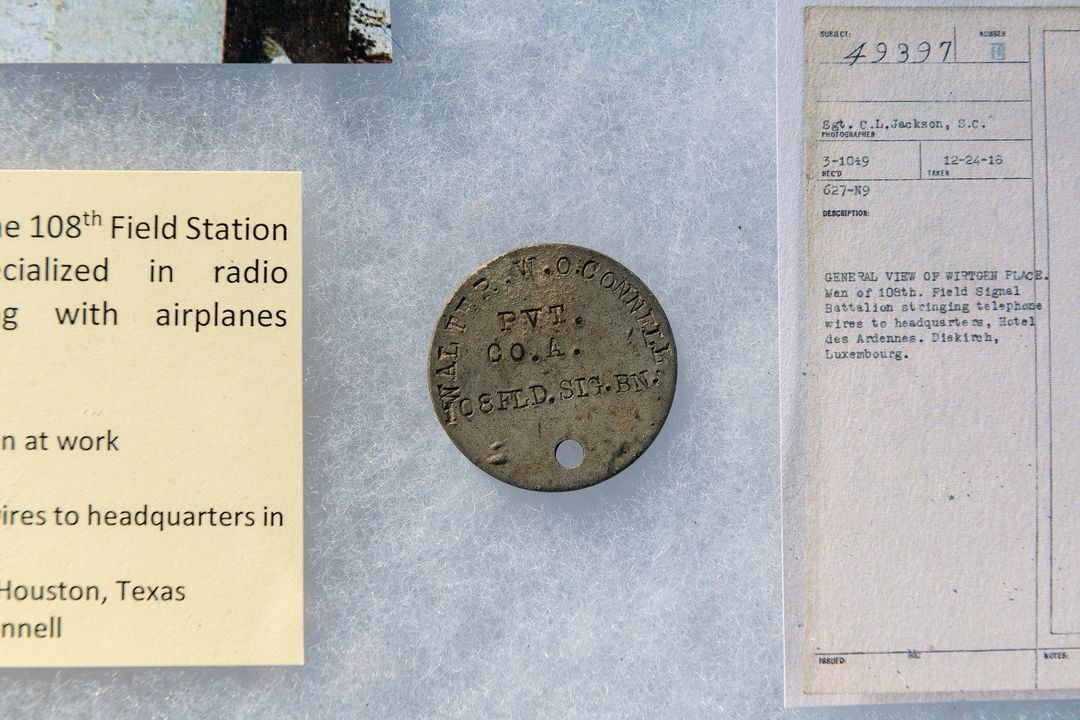

ThE TEXAS HISTORICAL COMMISSION HAD DECLARED the area to be ineligible for listing on the National Register of Historic Places. But last summer, as contractors at the Houston Arboretum & Nature Center started excavation for a conservation project for its Master Plan, all kinds of items began to turn up, including Welch’s Junior grape juice bottles, ink bottles linked to a Chicago manufacturer, construction materials, a uniform button, even a soldier’s dog tag.

Part of neighboring Memorial Park already had been declared a state archaeological landmark by the THC because of its visible foundation ruins from Camp Logan, a long-forgotten training ground erected in the park in 1917 for 45,000 soldiers sent down from the Illinois National Guard. It was one of 32 camps in the country set up by the federal government to quickly grow the U.S. Army from 300,000 soldiers to 2 million, to fight the first World War.

The new artifacts, the arboretum team knew, could help bring that history to life. So in spite of having the THC’s blessing to move forward with their project, they contacted the Houston Archeological Society about what they’d found, and by September of last year the arboretum, HAS, and local cultural resources firm Gray & Pape Heritage Management launched a volunteer-based emergency-salvage archaeological project to help recover Houston’s history before the soil is reused.

Mike Quennoz, an archaeologist with Gray & Pape who serves as Memorial Park Conservancy’s cultural heritage expert, has been working with volunteers on weekends to sift through roughly 42,000 pounds of soil. “We’re hoping to get as much information as possible from these piles that have been moved multiple times,” he says. “It’s not a traditional archaeological project with spatial information and context about how artifacts relate to one another.”

An artifact found at Camp Logan, beneath the Houston Arboretum & Nature Center.

Image: Anthony Rathbun

While newspaper archives, old postcards, and preserved copies of Camp Logan’s newsletters and photographs provide a look into the soldiers’ activities, the recently discovered artifacts serve as “real-life snapshots” that link historical and archaeological records. “There’s always additional information you can squeeze out of a space if you have the opportunity,” Quennoz explains. “Hopefully we’ll get some additional pieces about what life was like at Camp Logan.”

Co-author of the 2014 book Camp Logan, HAS president Linda Gorski is full of information about the camp whose heart lay near the railroad tracks on the western side of Memorial Park. A mile of trenches were dug just north of I-10 to train soldiers for trench warfare, she shares, adding that as part of their training, soldiers were exposed to low-level chemicals in tents sprawled over what is now the Somerset Green master-planned community, learning how to quickly outfit their gas masks.

Of course, Gorski jumped at the chance to learn more after hearing about the find at the arboretum. “These artifacts bring to life the story that we’ve already seen in letters and histories and newspapers,” she says.

The soldier’s tag, found at a spot in the arboretum that was probably used as a dumpsite when the federal government was leasing the land from the city more than a century ago, has been of particular interest to the team. They had his name, of course—Walter W. O’Connell—but were unable to locate anything in the way of official records, because many of those from World War I, and most likely O’Connell’s, were lost in a fire at the National Personnel Records Center in St. Louis in 1973.

Kids learn about the dig at the Houston Arboretum.

Image: Anthony Rathbun

So researchers turned to the internet, eventually connecting with his granddaughter via ancestry.com to learn more about him. They discovered that O’Connell had been a stenographer in Chicago before becoming a member of Company A of the 108th Field Signal Battalion, which specialized in radio communication with airplanes. His tents were located near today’s intersection of East Cowan Drive and Blossom Street— then a rural area.

In the world of archaeology, it’s incredibly rare to trace an artifact back to the individual who owned it, Quennoz says. And, because the public was so involved in helping recover the artifacts and offering information about O’Connell, the project has been nominated for the Council of Texas Archaeologists’ E. Mott Davis Award for Public Outreach, which recognizes endeavors that bridge the gap between professional archaeology and the public.

Some of the artifacts, like the ones pictured left, were recently on view at a special workshop at the arboretum’s Visitor Center. In the future, says Patti Bonnin, a naturalist there, the pieces will be on permanent exhibit. “That was one of the big selling points to doing this project,” she said. “We want a full display to honor what was here before.”