After a Brutal Murder, Houstonians Came Together to Fight for LGBTQ Rights

Members of Houston’s LGBTQ community had already waged a years-long battle against the AIDS epidemic and seen the repeal of a local nondiscrimination ordinance when Paul Broussard’s brutal murder sent shockwaves through the entire city, and then the nation, in 1991.

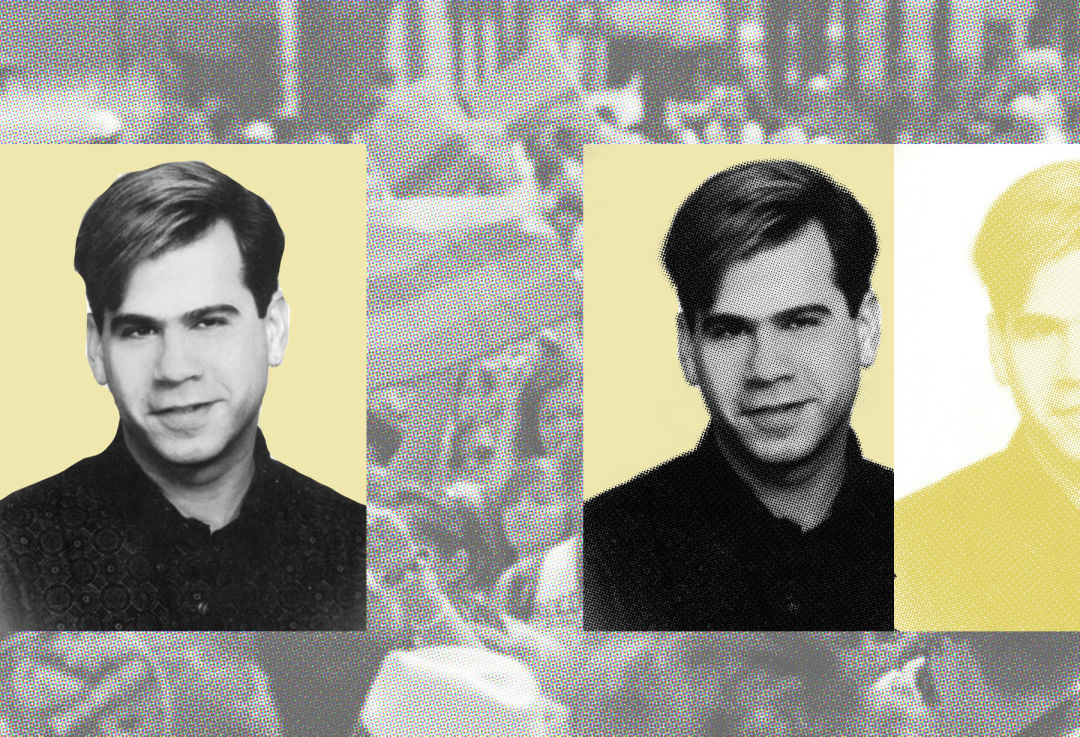

Broussard, a 27-year-old banker, and his two friends thought they were in safe territory walking through Montrose, the beating heart of Houston’s LGBTQ community since the 1970s, after sharing some drinks just after 2 a.m. on July 4, 1991. But then a group of 10 young men asked for directions to a local club, and the interaction swiftly turned violent. Though his two companions got away, Broussard was beaten and stabbed multiple times and left lying in a parking lot.

His story might have ended there, but so much of what happened that night and in the following days haunted Ray Hill and other local LGBTQ activists. Emergency responders were slow to answer in Montrose for fear of contracting AIDS (even in the early ’90s), so the EMS didn’t arrive until the early morning, leaving Broussard untended for hours. After he died from his wounds, the Houston Police Department, which had long had a contentious relationship with the gay community, did not seem intent on pursuing Broussard’s murderer. Frustrated, Hill and his colleagues sprang into action.

Image: Courtesy of Queer Nation

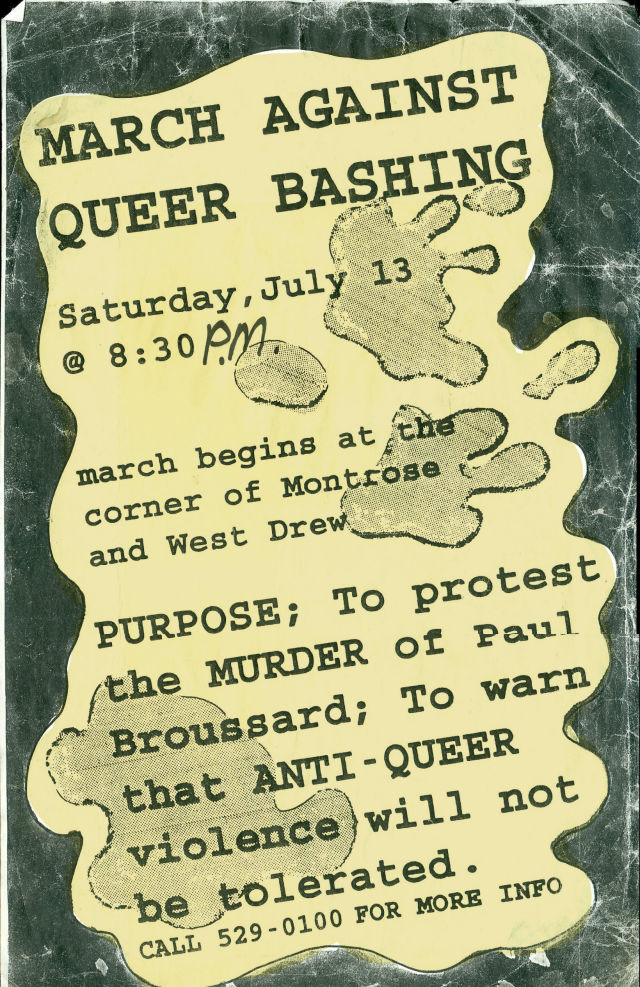

Soon the corner near Mary’s, the landmark gay bar where advocates had gathered to scatter the ashes of AIDS victims and publicly push for government help and equal rights in the decades prior, was the scene of a massive protest. The organizers expected a few hundred people to show up, but more than 2,000 gay and straight Houstonians flooded the streets.

“People knew about it outside of Houston,” says Brian Riedel, associate director of Rice’s Center for the Study of Women, Gender, and Sexuality. “It made headlines, and it was not just the queer press covering it.”

Broussard’s murder became a flashpoint, helping Houston’s LGBTQ community tap into a voice it would use to fight discrimination in the years to come. Just as importantly, it led to a citywide sense of solidarity that had not been previously seen.

“The incident brought us allies that hadn’t really considered the need for it before, that sense of shared vulnerability,” says former Houston mayor Annise Parker. “Paul Broussard could have been anybody’s son, anybody’s brother.”

In the months that followed, clergy members from Houston’s religious community spoke out against LGBTQ-targeted hate crimes, and further protests were held. HPD officers organized a sting operation to try to catch other homophobic aggressors, and those who went undercover as gay men were shocked by the harassment and physical violence they endured.

Over the next few years, HPD took further steps to bridge the gap between its officers and the city’s LGBTQ citizens, updating its definition of hate crimes to include those motivated by sexual orientation, helping to train Montrose’s newly established citizen patrol, and hiring the force’s first openly gay officer. The Houston City Council issued a resolution calling on the state legislature to pass a hate crimes bill.

And though it took a decade for one to be signed into state law—the 2001 James Byrd Jr. Hate Crimes Act, which includes the words “sexual preference” in its list of recognized prejudices—Broussard’s senseless death was a catalyst for its existence, as well as for the broader changes that have become a hallmark of the city’s character.

Annise Parker and wife Kathy Hubbard

In 1997, Parker became the first openly LGBTQ person elected to Houston City Council. In 2010, Houstonians elected her mayor, making her the first openly gay mayor of a major U.S. city. Since then, we’ve seen this city vote down the controversial “bathroom bill,” while the annual Pride Parade has become a part of Houston’s culture.

“The thing that makes the Broussard story matter now is that it is an example of community pressuring institutions to be accountable for the jobs those institutions are supposed to perform,” says Riedel.

Perhaps most tellingly, when the U.S. Supreme Court affirmed the legality of same-sex marriage in 2015, there were celebrations held across the city—not just in Montrose—and City Hall was lit up with the colors of the rainbow flag while couples lined up eagerly to be some of the first to exercise their legal rights to wed. At the time of Broussard’s death, none of this would have seemed possible.