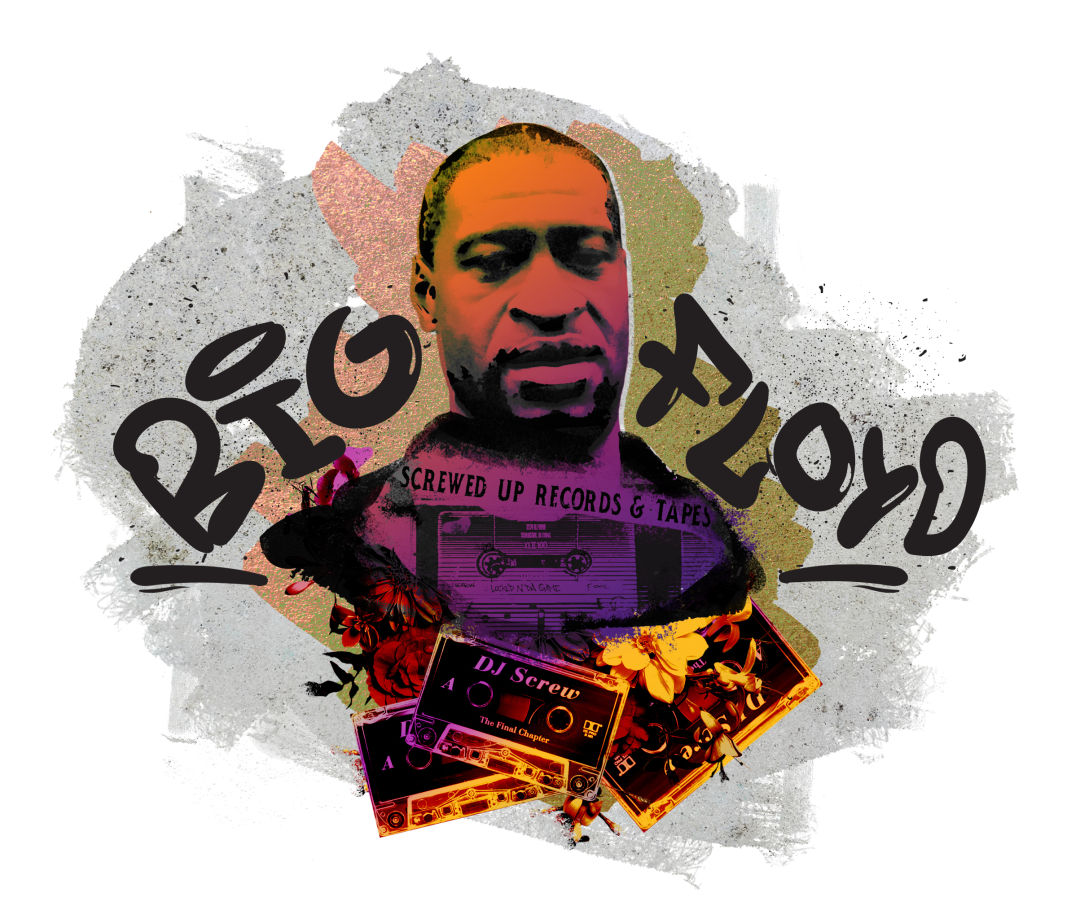

Remembering Big Floyd

His size made him impossible to miss, but in the community where he grew up, it was his heart—and his fearless freestyling—that made him impossible to forget.

A single phrase keeps being used to describe George Floyd, the 46-year-old black man and native Houstonian whose killing by Minneapolis police on Memorial Day sparked global outrage and protests across the country.

“'Gentle giant,' that’s what everybody called him,” says Houston rapper Cal Wayne, who describes Floyd as his adopted brother. “What made him so special was the way he treated people. Nobody could hate him. Anywhere we ever went, I’ve never seen anybody mad at him.”

Floyd was born in North Carolina, but his mother moved him and his siblings to Houston when he was just a baby, and he grew up in the Cuney Homes housing project in the Third Ward. He was a large man before he could even graduate Jack Yates High School, becoming a star tight end and a basketball player who would help take his teams to state playoffs. With his imposing 6-foot-7-inch frame and skills on the court and on the field, Floyd was most recognized for his high school sports career in those days.

But as hallowed as high school athletics are in the Lone Star State, he was also part of something even more crucial to Houston's history. As Floyd was coming up in the Third Ward, DJ Screw was creating the "chopped and screwed" sound that would put Houston hip-hop on the map. Floyd was young, but he gained entrance to the scene and made contributions to DJ Screw’s legendary Screwtapes. In the days following Floyd’s tragic death, which has sparked fierce protests against police brutality in his hometown, across the nation, and around the world, his music has resurfaced on social media, prompting many to honor his talent, and legacy as a member of one of Texas’s most historic music scenes.

“The entire hip-hop community of Houston and—from the words and messages I've gotten from people around the country—the entire hip-hop community nationwide, mourns and grieves the death of George Floyd, as well as adamantly pushing for justice for George Floyd,” Bayou City music fixture Bun B tells Houstonia. “I've gotten a word from almost every member of the Screwed Up Click about Floyd. It's a very close knit community so they're all mourning and grieving his death right now."

Growing up in Cuney Homes, Floyd shared the sports dreams of young men around the country, hoping to become the next Michael Jordan or Willie Frazier. His larger-than-life frame, which earned him the nickname “Big Floyd,” served him well as he helped propel Yates’ football team to the 1992 5A state championship game. The game, played against Temple, allowed Floyd to compete on the field of the Astrodome, which would've been a dazzling moment for any young Houstonian. Yates ultimately lost, but they held their own against the best team in the state on that beloved Houston field.

A year later, in 1993, he graduated with aspirations of playing in the NBA. Equipped with a basketball scholarship, he started studying at what is now South Florida State College, but the school wasn't a good fit for him. He returned home within a year and transferred to Texas A&M-Kingsville, says Wayne, who was taken in by Floyd's mother while his own mother was in prison. Wayne was living with Floyd and Floyd's family during those years.

Though Floyd’s college sports career ended when he dropped out during his sophomore year, the “Big Floyd” nickname followed him into his next stage of life. He used the name as he managed to become a small part of a vanguard of up-and-coming artists who would soon be renowned and simply referred to as the Screwed Up Click—Screw’s now-celebrated collective that would come to define Houston’s hip-hop scene on the national stage.

“Anybody who rapped on those tapes became legends, icons,” says former Swishahouse artist and self-professed first-gen ScrewHead Paul Wall. “Big Floyd was one of those people who was almost like a fictional character you’d read about in books.”

It happened almost by accident. In 1994, Floyd was back from Florida and a friend took him by Screw's house when they were laying some tracks. Floyd wasn't shy. He got on the mic, started rapping, and Screw liked what he heard. Under his well-worn moniker of Big Floyd, which befitted his deep, slow drawl, Floyd was soon freestyling over Screw’s sludgy chopped and screwed grooves, appearing on tracks including “Sittin’ on Top of the World,” where he gives a shout to the H-town tradition of “chopping blades,” ("up to the ghetto/this Third Ward, Texas/boys chopping blades on that mother f*ckin’ Lexus"), and “Tired of Ballin’.” After a callout from Screw himself around the 14-minute mark of the famed track, Floyd recounts popping home from college to record with S.U.C. and then continues spitting for two straight minutes, bragging about his b-ball skills and dreaming about drop-top Bentleys.

“Anybody who was on a freestyle, you had to have some type of courage,” says Wall, describing the track as the epitome of Screwtapes. “And if you went longer than 10, 15 seconds, you gotta have some type of talent.”

Big Floyd, who also appeared on a track in 2000 as part of another group, the Presidential Playas, freestyled on at least half a dozen of Screw’s famous mixtapes, if not more. And when he was on the mic, it was always about home. No matter how many rhymes he dropped, every one of Floyd’s contributions connected to the Third Ward somehow, says Wayne.

Floyd’s life was not without its lows; he faced a string of arrests from 1997 to 2007, according to Harris County District Court documents. However, things began to change in 2013, when, after serving four years for aggravated robbery at the Diboll Unit, a private state prison in East Texas, Floyd returned to the Third Ward, and started devoting his time to aiding the neighborhood and becoming a community leader. He used his social media platforms to speak out against violence, and worked with his church, Resurrection Houston, which offers ministry and support for residents of Cuney Homes. He would set up chairs before the services and help with the baptisms. He seemed intent on making a better life for himself and the people in his neighborhood.

Floyd also encouraged members of the next generation of Houston's hip-hop scene. He appeared in many of Wayne’s Third Ward-focused music videos, says the rapper. Wayne attributes his entire music career to his late friend, who was always on hand to encourage Wayne's ambitions, both inside and outside the studio. “Every video on my Instagram where I'm in the studio recording, he’s standing behind me dancing,” Wayne says. Floyd was also known to send messages of support, often for no particular reason. “Growth is gradual,” Floyd wrote to OMB Bloodbath in a message of encouragement that the young Third Ward rapper recently shared in an emotional Billboard essay about Floyd. “It’s only the beginning, and it’s so much coming your way.”

Seeking to further his own growth with a new beginning, Floyd moved to Minneapolis a few years ago. There, he worked as a security guard, a truck driver, and, prior to the pandemic, a bouncer at a club where he was once again known as “Big Floyd,” physically imposing, but also kind and thoughtful. “Always cheerful,” Jovanni Tunstrom, his former boss, told the Associated Press. “He would dance badly to make people laugh.”

Even after leaving the Bayou City though, Floyd remained devoted to the Third Ward and H-town’s hip-hop scene, supporting his friends, and family, and continuing to reach out to people in Houston's music scene. Even as he was working to build a new life in Minneapolis, he would still take time to motivate both veteran rappers and up-and-comers back home. "Everybody loved Floyd. This was his community. He wanted everybody to better themselves," Wayne says. Floyd and Wayne talked almost every day, and in the wake of his friend's violent death, Wayne says he is still struggling to figure out how to carry on. "I lost my biggest motivator," Wayne says. "It happened to the wrong person. He loved everybody."

Bun B didn't know Floyd, but his death just over a week ago prompted the famed rapper and Trae Tha Truth to organize a march with Floyd's family on Tuesday in Downtown Houston. "Even if he wasn't a rapper, we in Houston would still be standing up for his memory and for the injustice committed against him," Bun B says. "We don't want his legacy to be the video of him being tortured and murdered. ... We would love to see that George Floyd's death at the hands of the police would be the last act of that kind in this country. I think that would be a wonderful, lasting legacy for George Floyd."

Katelyn Landry contributed to this report.