Meet a Few of Houston’s Suffragists

When thinking of suffragists who fought for women’s rights, many universal figures probably pop into your head: Susan B. Anthony. Sojourner Truth. Elizabeth Cady Stanton. But what if you were asked to name a woman who transformed the Bayou City? Could you do it?

You might not know who many of them were (and there's so many more besides the women we focused on in this list), but we guarantee the causes they fought for have had a significant impact on how we live our daily lives. So, here’s to the women of Houston whose strength, passion, and determination never faltered. H-Town isn’t just a man’s world, and we have the women to thank for the city they created for us.

Hortense Sparks Ward (1872–1944)

Embodying a perfect storm of intelligence and strength mixed with a dash of poise and patience, Ward paved the way for women’s rights in Texas during the early 1900s. Ward began dropping jaws when she became the first woman to pass the Texas State Bar exam in 1910, and just three years later she was a key player in the enactment of the Married Women’s Property Rights Law, which let women keep control of their property even after marriage (before that, the husband had access to everything, no matter what the wife brought into the marriage). She followed that success up by lobbying the Texas Legislature to let women vote in the state’s primaries—a battle she and other suffragists won in 1918. In what should be a surprise to no one, Ward was the first woman in line to register to vote in Harris County.

But it wasn’t enough for just her to be able to vote; as president of the Houston Equal Suffrage Association, she wanted every eligible woman to sign up. Ward’s newspaper articles and pamphlet, Instructions for Women Voters, flooded across the state as part of a grassroots voter registration campaign that led to nearly 386,000 women registering to vote in just 17 days during the summer of 1918. Ward would continue to be politically active even after the ratification of the 19th Amendment, running for a Harris County judgeship in 1920 (she lost) and heading East to make speeches during the election of 1924 at the request of the Democratic National Committee.

Learn more about her at tshaonline.org.

Annette Finnigan (1873–1940)

The suffrage movement was forever changed when Annette Finnigan went to study at Wellesley College, a private women’s school in Massachusetts that employed an all-female faculty, and fell in with the active suffrage movement up North. When the Finnigan family, who had lived in Houston during part of Annette Finnigan’s childhood, returned to the Bayou City in 1903, she and her sisters would do the unthinkable. It took only a couple of hours and a dedicated group gathered in the Finnigan sisters’ home to establish the city’s first 20th-century suffrage campaign: the Houston Equal Suffrage League. Within three years, the sisters would move statewide and play a huge role in establishing the Texas Equal Suffrage Association (TESA), then called the Texas Woman Suffrage Association, where Annette Finnigan served as president from 1906 to 1908.

Though the Finnigans left Texas in 1908, leading to the disintegration of the city’s suffrage efforts, Annette Finnigan returned in 1912 to revive the movement, leading what is now known as the Women’s Political Union in Houston. Two years later she would resume her role as head of the TESA, writing countless letters and traveling across the state to spread the campaign for women’s rights during her second presidency. Annette Finnigan remained heavily involved in women’s suffrage efforts until a stroke in 1915 left her physically impaired. Her passion for the suffrage movement would always remain, but her later years were spent focusing on her love for art and travel—leading to her many generous donations to the MFAH that are still cherished by curators today.

Learn more about her at tshaonline.org.

Julia Ideson (1880-1945)

Ideson’s love for books began when she was just a girl flipping through pages at her father’s bookstore in Hastings, Nebraska. After her family moved to Houston in 1892, Ideson would go on to attend the University of Texas at Austin, excelling as a student in the university’s first-ever library science program. Upon her graduation in 1903, she would become the librarian at one of the Bayou City’s most cherished cornerstones: the Houston Public Library. Ideson’s numerous accomplishments over her 40-plus years at the library, including her efforts to seriously expand the library’s collection and her work in establishing the first library in the city for African American patrons—the Colored Carnegie Library—cemented her legacy in the Bayou City and led the city to name one of its central buildings after her.

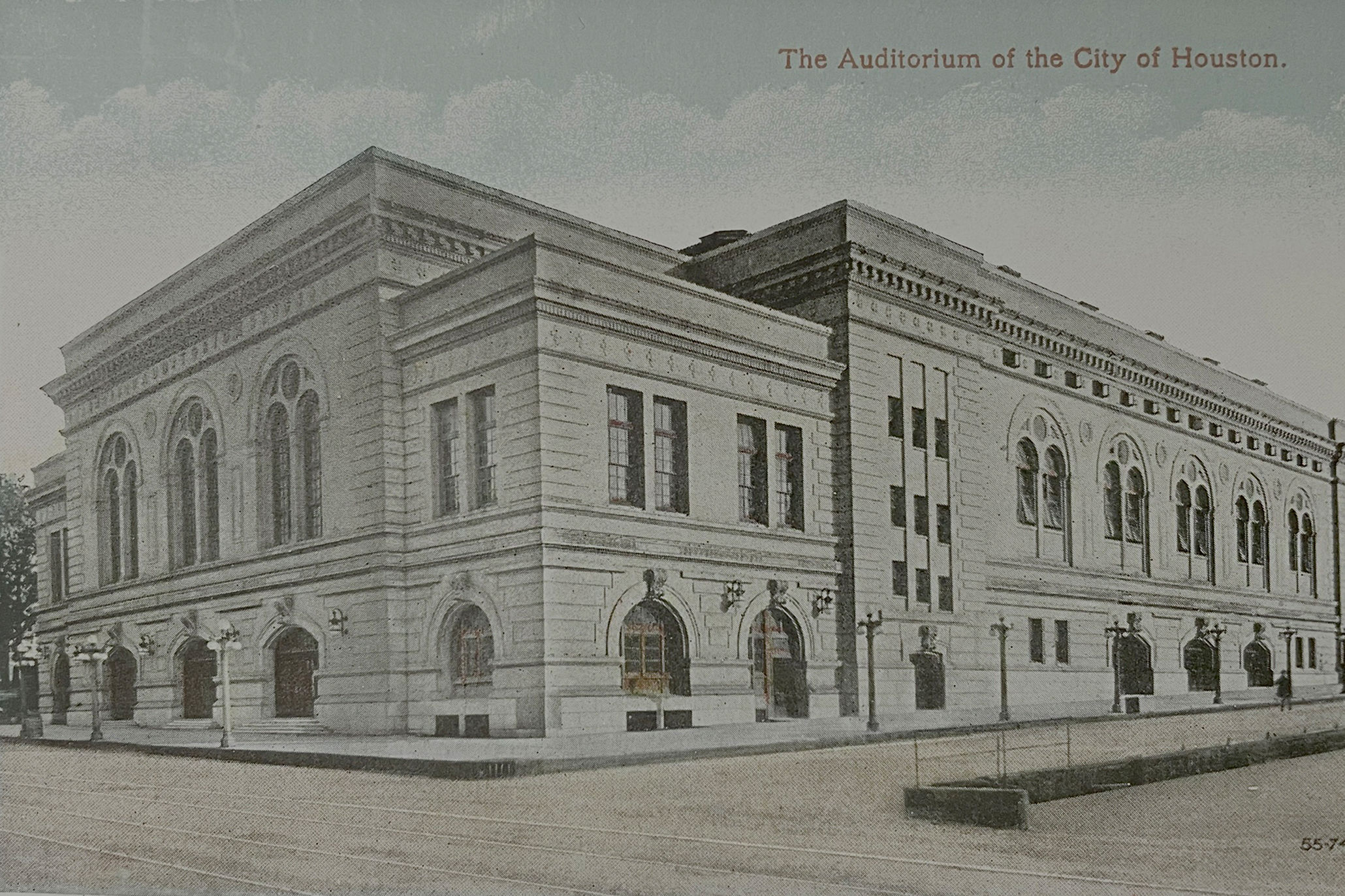

But Ideson did more than return books to their shelfs day in and day out. She was also a devoted suffragist, serving as an active member of the Women’s Political Union and even speaking at Texas’s first open-air woman suffrage rally in 1915. Even after the 19th Amendment became law, Ideson continued to fight for women’s rights, working with the League of Women Voters and the Houston Open Forum, which advocated for free speech by bringing distinguished—and often controversial—speakers to the city.

Learn more about her at houstonlibrary.org.

Eva Goldsmith (1880-1954)

The year is 1909. Eva Goldsmith is living at a boarding house for working women in Houston, where she earns a living manufacturing garments. After years of women enduring grueling work hours, horrid environments, and unfair pay, she brings these issues to the forefront when she sees her name hit headlines as an active member of various local labor unions.

By 1910 she was elected vice president of the Houston Labor Council, where she was selected to be its delegate at the Texas Federation of Labor meeting in Galveston. It was here that Goldsmith’s advocacy for labor and voting rights converged. Her powerful speech condemning then President William Howard Taft’s highly publicized anti-suffrage talk in Washington, D.C. caught the eye of the Texas Federation of Labor (TFL), which then “named Goldsmith as the representative to draft a resolution censuring Taft” for his stance, according to the Texas State Historical Association.

A few years later Goldsmith, who by then had become a force in the TFL, would go on to voice the plight of working-class women at an open-air rally, The Houston Review reported, and become chair of the Houston Women’s Political Union's ad hoc committee, which she represented at the Texas State Federation of Labor Convention in 1915. The following summer she campaigned against anti-suffrage candidates, according to Judith N. McArthur in her book, Creating the New Woman.

In addition to becoming a confidant of other Houston suffragist leaders, including Finnigan and Ideson, Goldsmith played an influential role in bringing working-class women into Texas’s suffrage movement, holding various informational seminars about the importance of voting in cities across the state. Goldsmith eventually moved to Oklahoma and then to Kansas, but her words, to this day, remain an embodiment of the power that drove the suffrage movement to success in Texas and the Bayou City.

Learn more about her at tshaonline.org.