Here’s How the Covid-19 Vaccines Actually Work

Fake news has been the battle cry of many in recent years, and even before the Moderna and Pfizer-BioNTech Covid-19 vaccines were authorized in December, rumors swirled around the safety of the vaccines. The vaccine will change your DNA! It injects you with a microchip so the government can track you!

But Houston Health Department Health Authority Dr. David Persse doesn’t buy into them, of course, and he urges the public to be skeptical of these claims. “If something sounds outlandish,” he says, “it’s probably outlandish.”

Still, there have been plenty of questions, not to mention fear, surrounding the two vaccines currently available, and how quickly they were developed. So we asked Persse to answer our own questions about just how the vaccines work.

Let’s start with biology. What’s the science behind the vaccine?

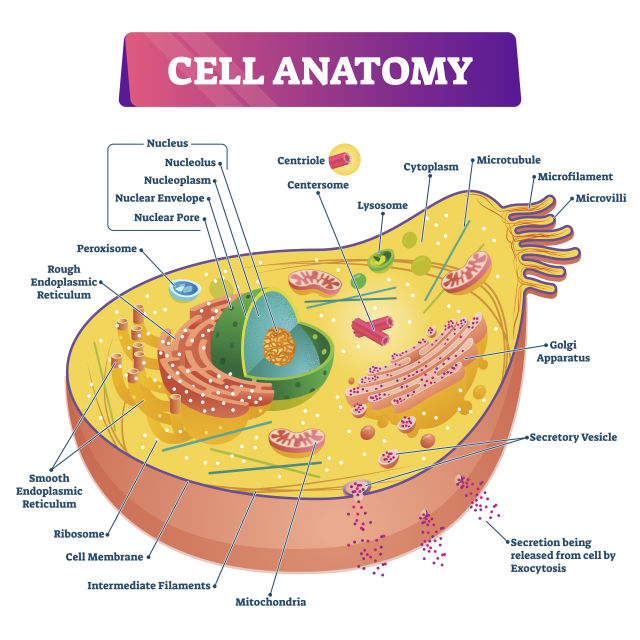

The way your cell works is the DNA in your nucleus is a code that tells the cell everything that it does. Different cells in your body wind up focusing on different parts of the DNA. Liver cells do different things than your kidney cells from your eye cells, etc. But they communicate to the cytoplasm—to the outside of the nucleus—through messenger RNA. So that’s what tells the cell what to really do.

So with the mRNA, vaccine, what it’s basically doing is it’s giving the cells the instruction code to create the protein, which’s been come to be known as the spike protein. And in order to do that, the mRNA vaccine uses a very small part of the mRNA of the virus to create the vaccine so that it will tell the cells to make the spike proteins. So the cells start making the spike proteins, and then a short period of time after, the mRNA dissolves. It doesn’t last very long. It gets in, it starts giving the information and then it falls apart, like all mRNA does. The mRNA that your body makes on your own—it only lasts for a short period.

Anything that is not you, your immune system will react to. By design, the mRNA vaccine causes your body to produce these spike proteins, which then your immune system recognizes isn’t supposed to be there and develops a response. And the whole reason for that is that it takes a while for your immune system to learn about this new thing that’s not supposed to be there. Anybody who’s not immunized and gets exposed to the coronavirus: during the time that it takes the immune system to recognize this isn’t supposed to be here and starts launching a response, in that period is when people become critically ill.

And so the idea is by teaching your immune system ahead of time, when you’re exposed to the coronavirus, you have an immediate reaction, to the point that the virus rally never gets the chance to cause any problems.

So basically, the vaccine gives your cells an order to make proteins that your body then reacts to and makes antibodies?

Exactly.

But what is mRNA?

mRNA is a specific sequence of amino acids. I sometimes tell people, think of it like a bar code, and each line is a different amino acid. It’s like a bar code, and your body has to read the whole thing. It’s a fragile molecule—this is one of the reasons why it has to be kept at cold temperatures, because it’s fragile—and it doesn’t last very long inside your body. It starts to fall apart. Just like if they kept it at room temperature, it wouldn’t last very long. Certainly not long enough from manufacture to injection.

While an mRNA vaccine is new, the technology behind it was first developed during the SARS outbreak in the early 2000s, right?

With the first SARS outbreak and with MERS (Middle Eastern Respiratory Syndrome), which are also coronaviruses, a lot of work was done to develop vaccines for them back then. That wound up [taking] years and years to do, because at that point, it really was all brand new. Fortunately, SARS-1—that outbreak was controlled and basically eliminated. And the MERS, while not eliminated, remains a low number of cases per year.

So the vaccine development basically stopped. But it’s all that work and all that research, and that technological development that was available when SARS-2 came along. All they needed to do was get the sequence of the coronavirus in order to be able to then start using this new technology to produce the MRNA vaccine. It’s not like we started from scratch last January. A decade’s worth of work was already sitting on the shelf.

Okay, now that we know the science, how long does it take for the body to develop antibodies after vaccination?

With the first shot, it looks like people aren’t developing any measurable amount of antibodies until about two weeks after your first shot. Then after the second shot, you start developing an adequate amount of antibodies about a week to 10 days after the second shot.

Is that why people have to get two shots?

Yes, that’s right. To put this into context, it’s not uncommon for vaccines. We are all way too old to remember, but when we were little kids, when we got our first MMR—Measles, Mumps, Rubella—that was a two-shot sequence. Anyone who’s gotten immunized or vaccinated against Hepatitis—your first time that was two shots. It’s not uncommon at all.

So the vaccine gives you antibodies to keep you from getting sick, but are you still contagious if you get infected?

This is a good question. The studies that were done didn’t specifically look at that. The studies that were done were to determine whether or not people would be critically ill or not, and that’s where the 95-percent difference was noted—95 percent of the people in the trial who became symptomatically ill were in the group that was not vaccinated. Only 5 percent of the people who became symptomatically ill were in the group that was vaccinated. …

It is anticipated that there would be very little of that [asymptomatic vaccinated people spreading the virus]. Nothing is 100 percent in medicine, so there will probably be some folks who would fit into that category. It’s anticipated to be a very small number, and certainly far fewer than in the group that wasn’t vaccinated.

If someone has previously had Covid-19, how long should they wait before they try to get a vaccine?

Certainly, they need to wait at least until they have no symptoms anymore at all. After that, they can probably go ahead and get vaccinated. There really shouldn’t be any longer wait required.

Does the vaccine work as a booster if you’ve already had the virus? This might be a silly question, but if so, should you only get one shot then?

The recommendation at this point is going to be two [shots], and here’s part of the reason why: Although this is not yet proven, it is suspected that the sicker you were with Covid, the more robust of a natural immunity may have developed. And it’s not proven, but that would make sense from a virology standpoint and an immunity standpoint.

So for those people who were minimally symptomatic, or certainly for people who had no symptoms, the anticipation will be that your natural immunity will be very minimal. And therefore, just one dose of the vaccine probably won’t be enough to give you long-lasting immunity.

And for those folks who got more seriously ill—and here’s where this all becomes very complicated very quickly—they may have become more seriously ill because their immune system isn’t terribly robust. So while they may have had a worse course of illness, they still can’t count on that to translate to a more robust immune protection.

And again, none of this is proven at this point. But this virus has only been around for a year.

What’s one myth about the vaccines you want to debunk?

One of the ones that I’ve heard is that the mRNA will alter your own DNA. A) It’s wrong. B) If you understand how the cell works, it’s not possible at all. RNA is not DNA. RNA does not change DNA. DNA is the template the cell uses to make its own RNA, not the other way around.

What do you say to people scared to get the vaccine?

This is what I say: Just looking at our own local data, if you take the number of people who we know have been infected with Covid, and divide it by the number of hospitalizations, it’s about 8 percent of the people who have tested positive wind up hospitalized. You could make the argument—and I wouldn’t argue against you—that would still be an overestimate because so many more people become infected that never test.

So let’s take that 8 percent and cut it in half to 4 percent, and just to be fair, let’s cut it in half again and make it a 2 percent risk that if you become infected, you would wind up being hospitalized. And we don’t know what the exact number is, but I try to be generous by cutting it in half and cutting it in half again.

A 2-percent risk is one in 50. If you look at the first 1.89 million Pfizer doses that were administered, there were 21 cases of anaphylaxis, which is a severe allergic reaction, and no deaths. So 21 out of 1.89 million is about one in 100,000. If I’m running the risk of one in 100,000 of having a severe reaction to the vaccine versus a one in 50 chance requiring hospitalizations should I become infected … I will take my chances with the vaccine any day.

Pfizer and Moderna were both approved by the Food and Drug Administration for emergency use. What exactly does that mean?

The FDA recognizes that the full cadre of investigations and research into the vaccine has not yet been completed that they would require. But because of the pandemic, the FDA feels that they have enough evidence that the benefits of the vaccine outweigh the apparent risks.

Are there extra protocols for these companies because of the emergency-use approval?

There are two levels: One is increased reporting requirements based on the vaccine that they give. In addition, they still need to continue with all of the normal requirements that would have been expected for them to get full authorization through the traditional methods.

When will most people be able to get the vaccine?

What we’ve been saying, just based on the projections coming from the federal government, is that the average person who meets no other special criteria can look forward to having the vaccine easily available to them by April.

What advice do you have for people who are looking to get a vaccine?

A couple of things. One is to continue to do all of your precautions—wearing masks, etc. And to please be patient.

Unfortunately, this is not always going to look like it’s fair and equitable, in spite of our best efforts, and I wish it were different, but please don’t get too frustrated with that. And as more and more vaccines become available, it’ll become less and less of a problem.

Anything else?

Be wary of the outlandish claims, be patient, and make informed decisions.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.