George Floyd’s Legacy Lives

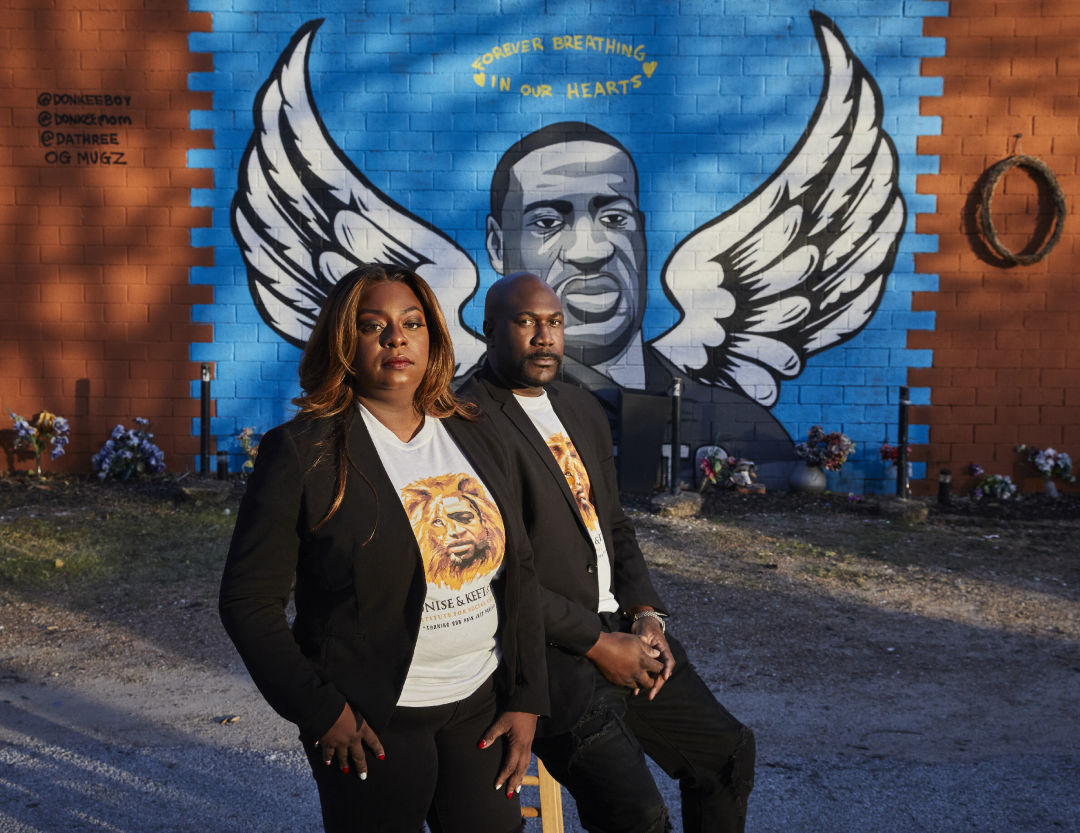

George Floyd's brother Philonise Floyd, and his wife Keeta, stand in front of The George Perry Floyd mural in Third Ward.

Image: Michael Starghill

Walking through the Third Ward neighborhood, where George Floyd’s family once lived, you can see the communal ties in real time. At the corner of Tierwester and Winbern Streets, adjacent to their now-condemned childhood home, lies the George Perry Floyd Jr. mural emblazoned on the side of Scott Food Mart, known to the locals as the “blue store.” Cars honk, and passersby stop to shake the hands of George’s older brother, Philonise Floyd, and his wife, Keeta, as a sign of respect and reverence.

George Floyd was killed on May 25, 2020, at the hands of the Minneapolis police, led by officer Derek Chauvin, who knelt on Floyd’s neck for more than nine minutes. Chauvin and three other officers, Tou Thao, J. Alexander Kueng, and Thomas K. Lane, have all been charged and sentenced: Chauvin for second-degree unintentional murder, third-degree murder, and second-degree manslaughter, and the other three for violating Floyd’s civil rights. To the general public, justice may have been served; however, the Floyds say that it doesn’t come close.

Nard Got Sole customized a pair of classic Air Force 1s for the Floyd family and their foundation, PAKFISC.

Image: Michael Starghill

“It can never be justice because I can’t get George back,” Philonise said. “Life is priceless. My brother was murdered. It is a death sentence for my family and I.”

But out of tragedy, some good has come. The Floyd’s never imagined a life of activism for themselves. Philonise, a former truck driver, and Keeta, a public health employee, now have a calendar filled with speaking engagements, conferences, and meetings with legislators on behalf of George. Thrust into a new, unfamiliar world of advocacy, the Floyds’ lives have been changed forever, and through it all they haven’t had adequate time to grieve their loved one.

“It’s truly been a journey,” Philonise said. “We’ve been through so much, from getting up in the wee hours of the morning for interviews where people ask, ‘Well, how are you doing?’ after seeing my brother slain on video. It’s been nonstop since the day he passed. When the rest of the world is asleep, we’re awake. After the news goes off, others can turn off their TV and step away from it and reset. We don’t have that privilege anymore.”

Philonise lovingly recalls his fondest memory of his brother before he became a martyr for police brutality. George was a family man and never hesitated to help others. He would carry their mother, Larcenia “Cissy” Floyd, around her Houston home, and the two would dance to Al Green’s “Love And Happiness.” It was Cissy, or “Mama,” who George Floyd poignantly called out for as Chauvin knelt on his neck. Cissy, who suffered from chronic strokes, died in May 2018. Philonise clings to those memories, as those are all that remain of his mother and brother. “I think he’s become a focal point for what’s going on in America, and racial justice,” Philonise said of his late brother. “So many people have begun to advocate for reform because they don’t want any more George Floyds. Parents are talking more with their kids about how my brother was murdered in broad daylight.”

Image: Michael Starghill

Thousands of people responded in a worldwide outcry to Floyd’s death, flooding the streets to protest his unjust killing. His death retold the cautionary tale in a way that sounded the alarm across the globe. “So many people will come up and tell me, ‘I know George is your brother, but he’s my brother, too,’” Philonise said. “I know he’s touched the entire world.”

However, the response to Floyd’s death led to polarizing opinions on how he died, something that has taken an emotional toll on the family. Misleading information from public figures like Kanye West and Candace Owens has cast a negative shadow on George Floyd in some circles. West doubled down on his claim that Floyd died from a fentanyl overdose rather than suffocating from a police officer’s knee on his neck. And Owens created an unflattering documentary about George’s life and the Black Lives Matter movement. The Floyds’ initial response wasn’t to fire back, but instead to educate and uplift.

“We typically try to stay away from the negativity,” Keeta said. “When we first woke up to the comments made by Kanye, we were disappointed and hurt. I really wish we had the opportunity to have a one-on-one conversation with Kanye. I think he missed the mark and missed it big time.”

With negative comments in their rearview, and the officers responsible serving their sentences, the work for the couple has only just begun. Now, nearly three years after George’s death, Philonise and Keeta are channeling their grief into a catalyst for racial and political progress with their new nonprofit organization, the Philonise and Keeta Floyd Institute for Social Change, or PAKFISC. Founded ahead of the Chauvin trial, PAKFISC has as its stated mission to influence public policy, assist in voter registration, enrich the community, and amplify the need for mental health in underserved communities.

Philonise holds up Third Ward resident Cal Wayne’s gold chain honoring his brother.

Image: Michael Starghill

“We were initially on boards with other institutions, and then we decided to resign from those positions and just start our own,” Keeta said. “Coincidentally, we received our 501(c)(3) status for PAKFISC on the first day of the Derek Chauvin trial. It showed us that we were on the right track.” The goal for PAKFISC is to effect change nationwide and beyond, starting with the city George called home.

Floyd’s death ignited the fire for a worldwide movement, but for Houstonians it hit so much closer to home. George was born in Fayetteville, North Carolina, but spent his childhood in Houston. He lived in the Cuney Homes projects in Third Ward, played sports, and attended Jack Yates High School.

“There’s still so much work to be done,” Keeta said. “We’re not going to downplay anything. There’s been police injustice in Houston as well. We want to work with these institutions and these entities to make sure that we make a difference. I really would love to see Houston be the epicenter of it, because this is home to us and George.”

George Floyd’s unimaginable death shook Houston communities—and the world at large—because it was a sobering reminder of life being Black in America. For African Americans in particular, Floyd’s death felt even more profound. Studies show that Black Americans face a collective sense of grief and trauma by the loss of so many lives at the hands of police in America. Many see themselves or their children reflected in the victims of police violence, another reason that honing in on mental health is vital for the Floyds.

Before his passing, George dealt with substance abuse, something that came as a surprise to his older brother. In court, George’s longtime girlfriend, Courtney Ross, confessed that the couple experienced an uphill battle with drug use. After George’s death, Philonise said he struggles with mental health, suffering from nightmares and twitches from constantly having to relive the murder of his brother over the past three years.

“Stress is something that has been killing a lot of people of color for years,” Philonise said. “It goes beyond racism—as Black people especially, we stress constantly about every little thing. And stress leads to long-term anxiety, depression, and other issues relating to mental health.”

Philonise and Keeta’s overarching goal is to shift the narrative within Houston’s community and beyond—something that Keeta said is emotionally heavy but rewarding. “One of the most impactful things from the work we’ve done,” Keeta said, “is going out to those underserved communities and touching those families, letting them know that we care and they’re not forgotten about. I think often they are surprised that we bring that level of awareness to them.”

Their neighborhood visits include educating families on the importance of health and wellness, voting, and voter registration, as well as political issues that directly affect them. “Accountability begins at the local level,” Keeta said. “It’s up to us to hold the people we elect into office accountable. That’s where we decided to step in and educate our communities—to hope for a better tomorrow.”

Their work today is a direct reflection and embodiment of the person George Floyd was. “The fact that we get a chance to help make change makes us feel a lot better about who we are today,” Philonise said. “We can do it ourselves, but we’re stronger in numbers.”