How to Spot the Remnants of Houston’s Rails

Image: simonkr/iStock

Every month in Houstonia, James Glassman, a.k.a the Houstorian, sheds light on a piece of the city’s history.

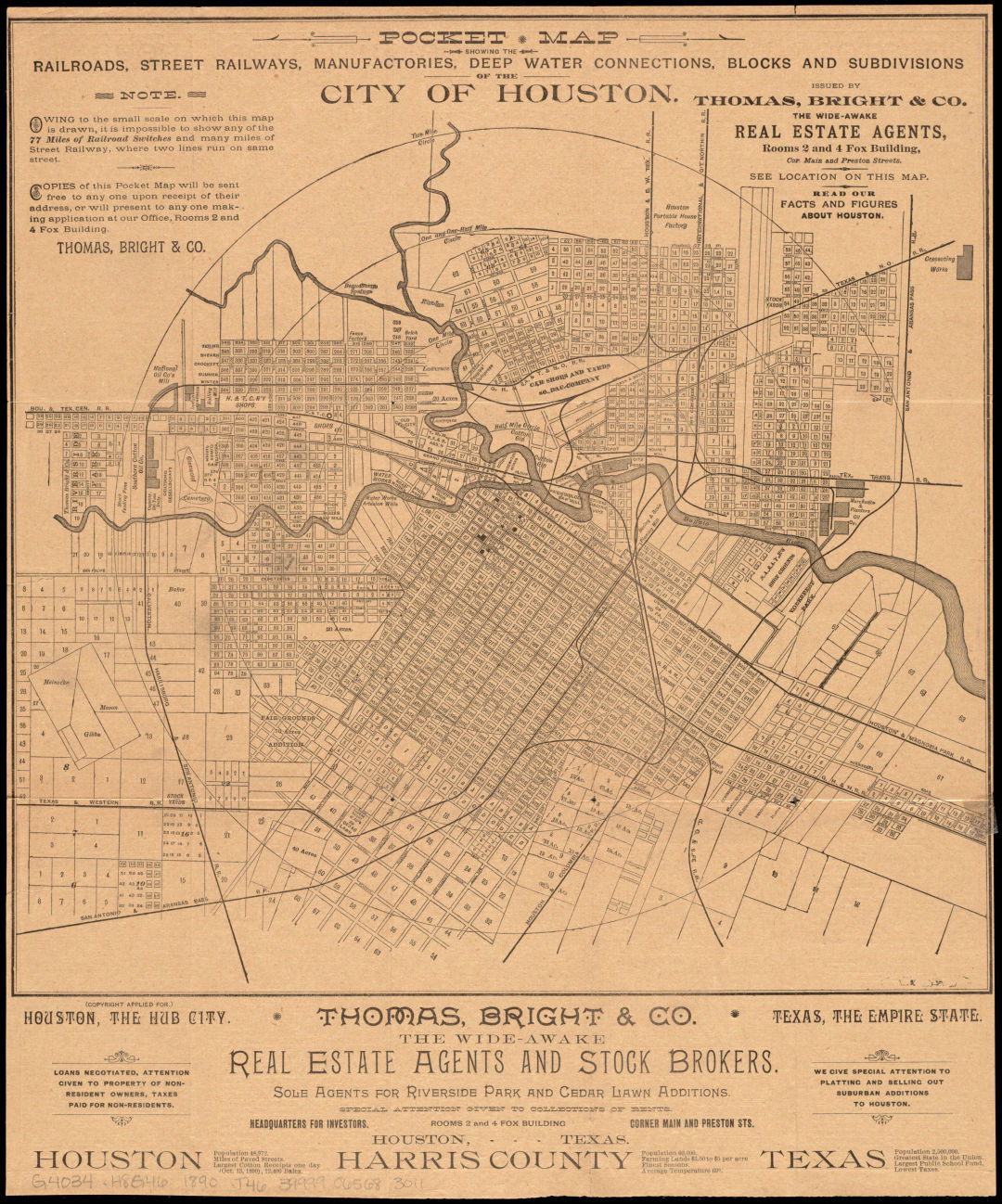

Houston loves the future. As a boomtown, it’s always been smitten with tomorrow, and occasionally scornful of yesterday. How ironic that the current city seal features an old-timey steam locomotive, which upon its debut in 1840, was an aspirational vision of a future dreamed up by mayor Francis Moore. Technology will lead us! Today, the nineteenth century locomotive looks quaint at best, and alien at worst. (We have even stranger feelings about the plow underneath it.) There are a few physical reminders of the influence railroads had pre–Space City, but old-fashioned exploring reveals plenty of Houston’s ancient rail remnants.

It was decades following the introduction of the city seal that railroads finally appeared in Houston. From the 1870s onward—and well into the popularization of the automobile, trucking, and shipping—railroads allowed Houston to become nothing short of the Energy Capital of the World.

Image: piemags/DCM/Alamy Stock

As early as 1913, Houston’s Chamber of Commerce boasted that the booming city was “where 17 railroads meet the sea.” They made sure the catchy slogan made it into print, and later radio advertisements throughout the first half of the twentieth century.

In contrast with that era, today’s passenger train traffic is limited to Amtrak’s Sunset Limited line connecting New Orleans (nine hours) and Los Angeles (days). Commuter rail feels like science fiction to most of us inveterate drivers. And that super long freight train stopping traffic is likely carrying petrochemicals, raw materials, or bulk cargoes. All vital to Houston’s economy.

In the former heart of industrial Houston, Commerce Street (get it?) and several remaining warehouse district buildings showcase the once-dominance of rail. Even though the tracks are long gone on streets like Sterrett, existing loading docks sit at box car door height. Back when the Ship Channel was mostly just wharves at Allen’s Landing, freight switched from steamship to train at the famed foot of Main Street. The Cotton Exchange and Southern Pacific buildings sprung up in those blocks to serve the bustling rail traffic. Today, the train squeezes underneath the University of Houston Downtown’s main building daily on its east-west routes. To the north, another set of mostly parallel Union Pacific tracks zip over I-45 at the rail viaduct hosting Houston’s beloved graffiti “BE SOMEONE.”

Image: thatonekid-josh/alamy

Maybe you’re reading this while you’re stuck waiting for a train to pass, historically common for residents of the East End, where railroad tracks seem to outnumber streets, and freight trains have been known to just stop. They doubtless wish for more rail remnants than actual rail. Will local politicians ever be able to reroute these unneighborly barriers? In 2017, MTA completed its bridge over the Union Pacific East Belt freight rail line to serve its MetroRail Green Line. And in the coming months, the beleaguered neighborhood will receive four underpasses at Houston Belt & Terminal Railroad line and major road intersections.

The Port of Houston is to blame for that rail traffic nightmare. Specifically, it’s the refineries and chemical plants that send their products from Houston to the rest of the nation, but first have to wiggle through the concentrated tangle of tracks that overlay the predominantly residential East End. The Near Northside and Fifth Ward have their own series of well-used freight lines, and irked residents too.

Other railway remnants can be found in the new, recreational concrete paths, converted from rail lines, commonly known as Rails to Trails. Since 2009, the 10-foot-wide, 4-mile-long Columbia Tap Trail replaced the abandoned Columbia Tap line that had unceremoniously bisected Third Ward and the Texas Southern University campus for decades. The walking and biking path connects the northern portion of Third Ward (now considered “EaDo”), across Brays Bayou, to the eastern border of the Texas Medical Center.

Image: Peter Molick

Its similarly paved sister, the Heights Hike and Bike Trail, runs from downtown to the northern edge of the Heights. The trail replaced segments of the Southern Pacific and MKT lines and crosses White Oak Bayou at three points. The tracks that ran the length of Nicholson Street, often a few feet from the front doors of houses there, are long gone.

Sometimes rail remnants can inspire pedestrian bridges. The Rosemont Bridges over Buffalo Bayou, just east of Studemont, are built on the abandoned Galveston, Harrisburg & San Antonio Railway concrete embankment structure that extended the rail line into pre-Montrose in 1880. That line died at the dawn of the twentieth century when Montrose and its mini-neighborhoods were platted, but you can see the slightest remains of its alignment in the curve of Grant Street.

Buffalo Bayou Partnership hosts pontoon boat tours highlighting Allen’s Landing, where Houston’s grungy, industrial past hides underneath modern freeways. The most dramatic of the abandoned structures is the Strauss Bascule Bridge. Built for the Houston Belt and Terminal Railway Company in 1912, the drawbridge sits in stark contrast to US 59 overhead. While vegetation has reclaimed most of the widened waterway, the painted steel bridge is a glorious memorial to the Industrial Era. The Partnership is also responsible for including the derelict bridge into its expansive, paved hike and bike network.

Image: James Glassman

Speaking of Houstonians’ current means of travel, many of the city’s freeways were mapped out over rail lines. When looking for a decent route out of town, an existing, vacant right-of-way is a good place to build the path to the future (or in this case, Victoria). To that point, portions of the Southwest Freeway and its neighbor Westpark aligned with the Southern Pacific line, which dated back to 1914.

And in the best example of 100 percent rail eradication, look at the Missouri-Kansas-Texas line, which inspired the Katy Freeway alignment—then swallowed it whole. The tracks eventually reappear in Katy, aptly named for the M-K-T, as legend has it.

Houston’s biggest rail-era artifact is none other than the home to our beloved, two-time world champion Astros. Ever wonder why there’s a locomotive above left field at Minute Maid Park? In a slightly-out-of-character move, Houston reused the decades-abandoned Union Station on the east side of downtown, transforming the grand lobby into a striking entrance for baseball (and architecture) fans.