Dr. Peter Hotez’s Fight for Vaccines Is Not Just in the Lab

Among the framed commendations, awards, newspaper clippings, and a child’s crayon drawing that adorn the office walls of Dr. Peter Hotez, one letter stands out—a neatly typed note from the Obama administration. It’s a polite thank-you for his service as a US Science Envoy, written shortly after President Donald Trump was elected in 2016. Hotez had inquired if he still had the role the administration gave him the previous year. “I guess that was my answer,” Hotez says with a laugh.

The letter is a curious artifact in Hotez’s office. Unlike the joyous knickknacks that celebrate the scientist’s greatest accomplishments, it represents the uneasy intersection of his work as a scientist with the turbulent world of culture politics and partisan divides—a reality he’s grappled with more intensely in recent years.

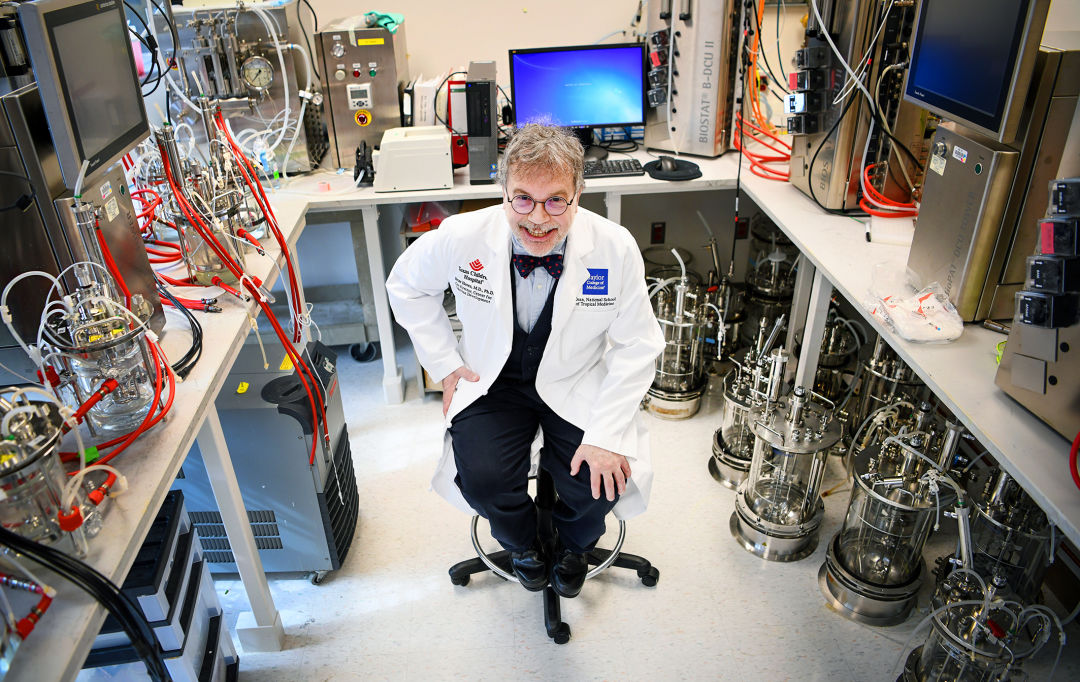

Hotez, 66—a pediatrician, codirector of the Texas Children’s Hospital Center for Vaccine Development, and dean of Baylor College of Medicine’s National School of Tropical Medicine—has spent much of his career at the forefront of vaccine research and global health advocacy. For decades, his work has focused on neglected tropical diseases, creating low-cost vaccines for illnesses like hookworm and schistosomiasis, which disproportionately affect impoverished communities around the world. This is the work Hotez describes as his lifelong quest. One he has had since childhood.

As a young boy in West Hartford, Connecticut, Hotez would visit his local library and pore over science books, fascinated by the world of microorganisms and diseases. Among them was a textbook on parasitology, which would become the foundation of his career. Decades later, he would return to that same library to find the book still on the shelf, his name the last stamped on its checkout card.

Hotez attended Yale University as an undergraduate and later pursued an MD-PhD at Cornell and Rockefeller University, where he began developing his first vaccine, aimed at combating hookworm anemia. This “OG vaccine,” as he calls it, remains one of his proudest achievements. Now in clinical trials, it represents the culmination of more than 40 years of research and persistence.

“I always wanted to be that person that made vaccines,” Hotez says. “The fact that happened was probably the single most fulfilling aspect of my life. Now I want to reproduce it.”

Yet despite his groundbreaking contributions, Hotez has found himself increasingly pulled into battles far beyond the lab bench. The rise of vaccine misinformation and the politicization of public health have placed him squarely in the crosshairs of the anti-vaccine movement, bolstered by online conspiracy theorists as well as political figures. Last November, Trump nominated notorious anti-vaccine activist Robert F. Kennedy, Jr. to be his Health and Human Services secretary.

“Before, the anti-vaccine movement was a fringe movement; now I see it broadening,” he warns. “This is going to be a big problem that we face.”

The once-isolated pockets of the anti-vax movement have now grown into a well-organized and increasingly influential force spanning political, geographic, and cultural divides. For Hotez, the fight against this tide of misinformation is deeply personal. In 2018, he wrote Vaccines Did Not Cause Rachel’s Autism: My Journey as a Vaccine Scientist, Pediatrician, and Autism Dad, a book that addressed and debunked the long-standing myth linking vaccines to autism. As the father of a daughter with the neurodevelopmental disorder, Hotez had a unique perspective and an undeniable stake in setting the record straight.

“I saw the anti-vaccine movement gaining strength and power, and I didn’t see anybody stepping up and explaining why vaccines were safe and not causing autism in straightforward language. I felt an obligation and now I realize that speaking out [and] defending vaccines may turn out to be as important as the vaccines that we actually make for the world because we’re in such dangerous times right now,” Hotez says.

The release of the book, and his outspoken defense of science and vaccines during the COVID-19 pandemic two years later, further thrust him into the public eye—and made him a target. Online harassment, death threats, and public vilification have become part of his daily reality.

“Sometimes people will send me emails—threatening emails, nasty emails—and the first thing I’ll say is, ‘Read more broadly. Don’t just read your conspiracy sites,’” he says.

One of the challenges Hotez wrestles with is how to decouple science from politics—a task that feels increasingly Sisyphean as public health interventions are viewed through a partisan lens. He traces the roots of this shift to the growing influence of anti-science rhetoric.

“I worry that public health could collapse in the United States. Vaccines are first, but they’re going to go up against other public health interventions. That’s problem number one,” he says. “It’s not just attacking the science or the public health, it’s attacking the scientists and portraying scientists as public enemies or enemies of the state. The consequence of that is nobody’s going to want to become a scientist.”

Despite the mounting challenges, Hotez finds reasons for hope. His team at the Texas Children’s Hospital Center for Vaccine Development continues to produce low-cost vaccines for diseases that disproportionately affect low- and middle-income countries. Their COVID-19 vaccine developed with Baylor College of Medicine, Corbevax, reached over 100 million people in India and Indonesia, proving that lifesaving interventions don’t have to come exclusively from large pharmaceutical companies. The vaccine earned Hotez and his colleague Maria Elena Bottazzi a Nobel Peace Prize nomination in 2022.

Hotez has also turned his attention to addressing the health impacts of climate change and urbanization, particularly in Texas and the Gulf Coast. With diseases like dengue, chikungunya, and malaria on the rise due to warming temperatures and shifting ecological patterns, his team is expanding its focus to include genomic surveillance and early-warning systems.

“We’re in a disease-endemic region,” he says. “The Gulf Coast is becoming the epicenter of tropical diseases in the United States.”

For all the challenges he faces, Hotez still approaches his work with the same determination that drove him as a child checking out parasitology books from the library. Beyond developing vaccines, he spends much of his time connecting with communities—whether it’s inviting local groups to tour his lab, speaking at schools and churches, or mentoring young scientists.

“I want people to see us as real,” he says. “We’re not these shadowy figures in white coats plotting nefarious things. We became scientists because we wanted to do good in the world.”

Correction: An earlier version of this story stated a letter to Dr. Peter Hotez was from the Trump administration. It was from the Obama administration.