25 Years Ago, Minute Maid Park Was a Feat in Historic Redevelopment

Every month in Houstonia, James Glassman, a.k.a the Houstorian, sheds light on a piece of the city’s history.

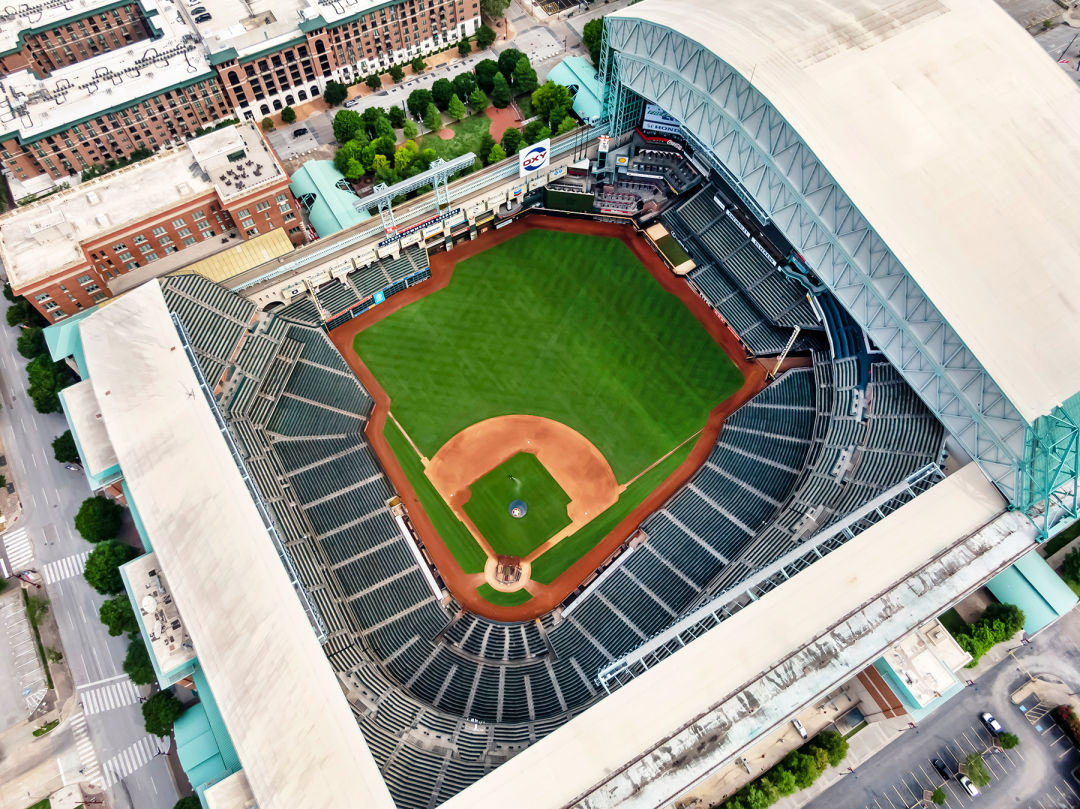

You’ve heard me lament that Houston has a history problem. We’re such a forward-looking city that we tend to forget our own landmarks. But the good news is Houston’s historic preservation community of architects, engineers, archeologists, and yes, developers has matured in the past few decades into a politically savvy bunch. They’ve shown us that an old, abandoned building can be saved, or even be the anchor for a brand-new idea in Houston: historic redevelopment. A great example of this is found at Minute Maid Park, home of two-time world championship winners Houston Astros, celebrating their 25th season at the downtown address.

By the mid 1990s, Houston Astros owner Drayton McLane Jr. was sending signals that he wanted to improve the fortunes of his team with a new ballpark, either in Houston, or perhaps outside of Washington, DC. This was a well-known owner-versus-city bluffing game, or maybe just an unfancy ultimatum. Either way, McLane began working with the architecture firm HOK Sports on stadium ideas. The group had just recently reinvented ballparks—or simply reminded American baseball fans that they could, or should, tap into the inherent nostalgia of the national pastime through their design. Baltimore opened the HOK-designed Oriole Park at Camden Yards in 1992 to universal acclaim. This brand-new but old-feeling ballpark was attached to the back end of Baltimore & Ohio Warehouse. And the best part was that it looked like it had always been there.

Hey, we could do that here! We even have a similar unused landmark in a forgotten corner of downtown just begging to be redeveloped. And bringing baseball to the city’s center could be an antidote to its unchecked sprawl. For years, city leaders had longed for and attempted development projects for the Central Business District. George R. Brown Convention Center finished its first major upgrade in 2003, and the 12-acre Discovery Green wouldn’t open until 2008. Even Market Square had yet to receive the public-private partnership makeover that had worked so well at Hermann Park, and would later be the model for Memorial Park, Discovery Green, and Emancipation Park. In the early 2000s, all downtown streets got an upgrade with repaired sidewalks, live oaks, colorful wayfinding, and civic art.

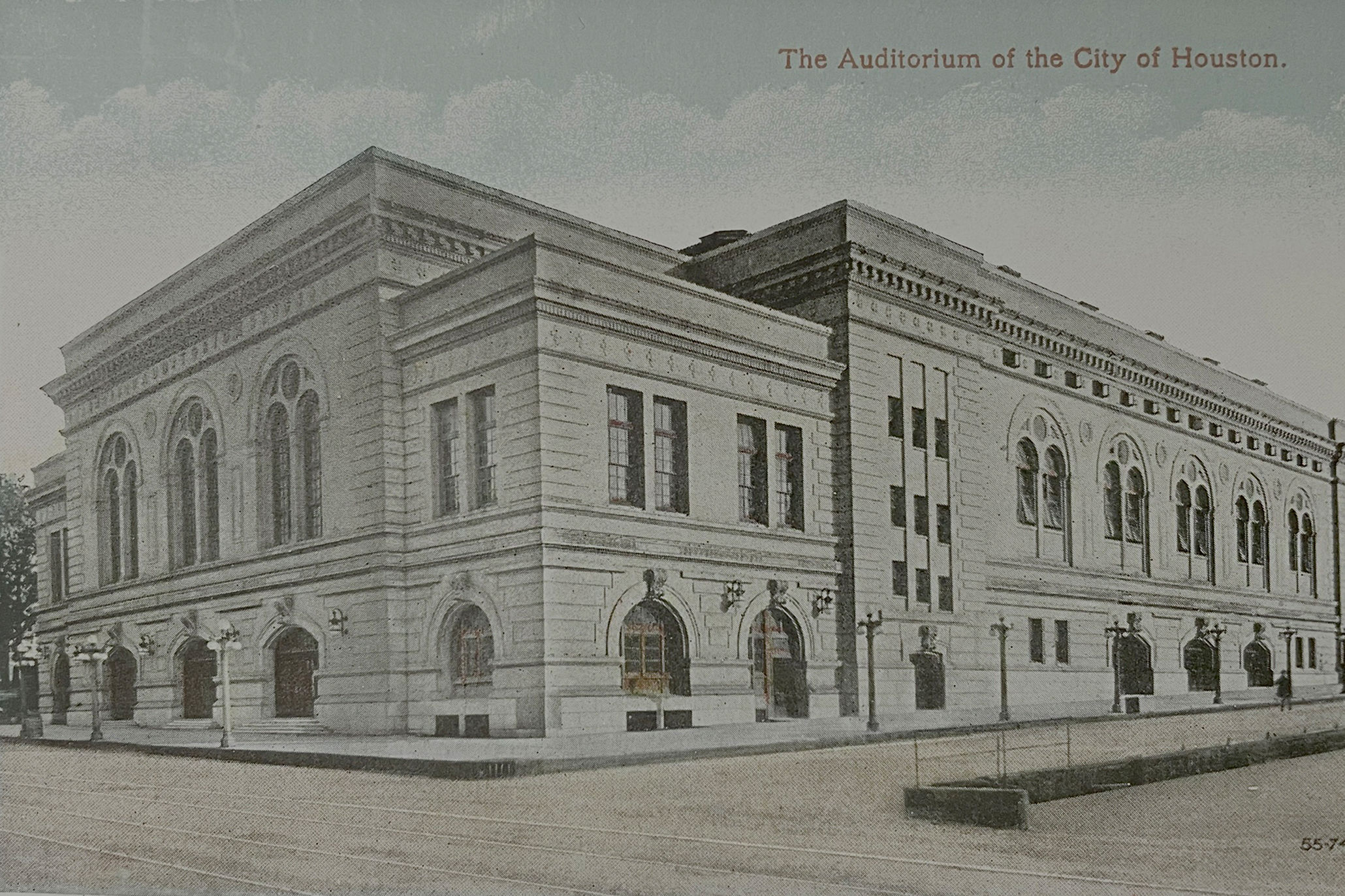

Image: Courtesy James Glassman

But in the waning part of the twentieth century, there was nothing significant between Main Street and the shuttered Union Station aside from a sea of surface parking lots used by commuting courthouse employees, lawyers, and jurors. And after sunset, you weren’t likely to see any signs of life in those desolate stretches. Of course, the Union Station site had rows of tracks for passenger and freight trains stretching behind the concourse, so its overall footprint would be sufficient to house a ballpark and required amenities, like VIP parking, a back office, and a team store.

The Houston Belt and Terminal Railway Company had originally hired New York architects Warren and Wetmore to design the two-story station, opening it in 1911. The next year, they added two more floors, as it looks today. The dramatic double-height, vaulted main concourse and lobby remains, now enhancing fans’ excitement upon arrival at Minute Maid Park. It also doubles as an event space.

With the entrance facing Crawford Street and just a block south of Congress Street, Union Station was effectively on the border of the Second and Third Wards. The impressive train station contrasted with the mostly residential neighborhood, and ultimately hastened the transformation of the area, still blocks away from the downtown of the day, into light industrial. Many of those adjacent blocks still have warehouses from the era.

In 1974, dwindling passenger train service was relocated to the west side of downtown at the old Southern Pacific Grand Central Station site (the building itself had already been replaced by the Central Post Office, but the tracks remained behind the new building). Today, there is a working, albeit minuscule, Amtrak station on those tracks, west of Post Houston.

In 1996, voters approved a $180 million bond for a new stadium downtown. The newly dubbed Ballpark at Union Station would feature soaring, arched steel columns supporting trusses, more intimate seating closer to the field, a real grass playing surface, and a retractable roof. Some Houstonians, who had only ever attended games in the climate-controlled Astrodome, thought the latter was a joke—surely locals aren’t interested in being outside. They built it anyway. The roof opens quickly and dramatically, but home field advantage is heightened when the fans’ cheers are contained when it’s closed.

Enron shelled out $100 million to have the naming rights for the ballpark when it opened on March 30, 2000. Since Enron’s corporate implosion, the Astros’ friendly confines have been known as Minute Maid Park. Obvious and not-so-obvious details abound. Have you ever noticed VIP Astros fans on the roof of Union Station during a game? Or the 422-foot marker under the window of the top floor indicating the distance from home plate? And yes, those are (fake) oranges being hauled by the steam locomotive over left field.

Preservationists wondered if it would be possible to love both the rookie Minute Maid Park and the veteran Astrodome. The beloved and erstwhile signature landmark was audacious and spacious, but certainly not intimate. So vast it would urge you to ponder your place in the universe. Great for awe and self-reflection. Not great for homers. Today, the nonprofit Astrodome Conservancy is committed to delivering a viable plan for the former home of Houston baseball, football, and rodeo.

Baseball, as an American institution, provides an overflowing toy chest of retro icons, imagery, and let’s not forget my favorite: typefaces. The then-new Astros uniforms straightened the slanted star; ditched the ’90s midnight blue and gold for brick red and pinstripes; and changed the font to one that could simply be characterized as “baseball-y.” When they were finished with the new jerseys, all of the 1960s and ’70s Space Age Astros vibes were left behind in the Dome (at least until throwback uniform game nights). Fortunately, we got a return to classic orange (and current) Astros uniforms in 2013, and railroad-themed mascot Junction Jack was sent to the showers, replaced by an updated throwback, the green and fuzzy Orbit. The current Astros look is the perfect balance of retro and contemporary.

And the area is certainly lively before and after games and concerts. Around the park are high and low multifamily apartment buildings and luxury hotels. MetroRail’s purple and green lines zip fans to and from ticketed events. Recently, the Astros promised a new multiblock, year-round public destination and experience to attract more pedestrians to Minute Maid Park’s micro neighborhood. And maybe they’ll rehire Junction Jack to fill in when Orbit needs a night off.