Das Rheingold: Behind the Scenes

Image: Lynn Lane

Das Rheingold

April 11–26

$40–390

Brown Theater, Wortham Theater Center

501 Texas Ave

713-228-6737

hgo.org

On a recent Friday afternoon, a visitor to the Wortham Theater Center’s cavernous Brown Theater—home to both the Houston Grand Opera and the Houston Ballet—could have been forgiven for thinking that he had stepped onto the set of a new James Cameron movie.

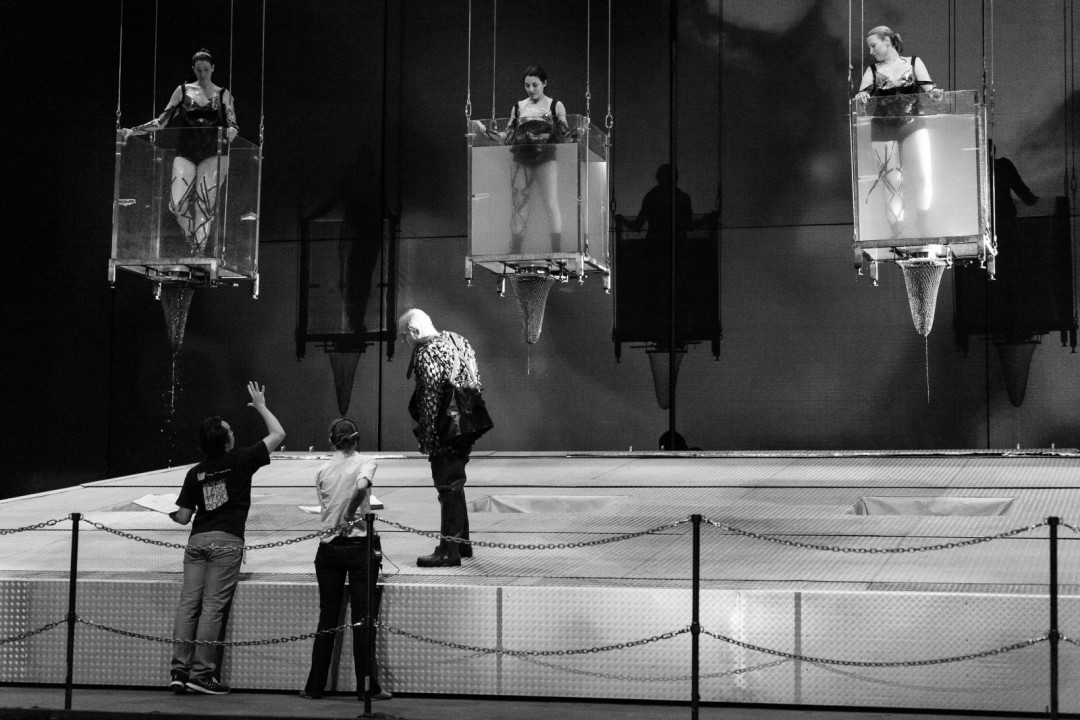

A huge steel platform, angled slightly toward the audience, occupied much of the stage. Embedded in the platform were three washing machine–size aquariums, each filled nearly to the top with water. (Or they were supposed to be—one of them had developed a leak and was empty). Inside the transparent acrylic tanks, bobbing up and down, turning underwater flips, and contorting themselves into various painful-looking positions, were three women in 1930s-style bathing suits, two brunettes, and one blonde, all sporting black athletic tape on their arms and legs and covered from head to toe in what looked like Saran Wrap.

The Rheinmaidens, mermaid-like creatures who guard the gold at the bottom of the Rhine, are the first characters to appear in Das Rheingold, the first chapter of Richard Wagner’s 15-hour, four-part music drama Der Ring des Niebelungen, which the Houston Grand Opera is staging for the first time in its history beginning on Friday night with the premiere of Rheingold and continuing for the next three years, with a new chapter debuting each season until the grand finale, Götterdämmerung, concludes the cycle in Spring 2017.

This is not your parents’ Ring Cycle. The HGO is staging an experimental production by Catalonian theater company La Fura dels Baus that features futuristic costumes, acrobats, state-of-the-art video projections, and, yes, Rheinmaidens in fish tanks.

Before a recent technical rehearsal, the cast and crew gathered in the orchestra seats to receive their marching orders from HGO technical and production director David Feheley. “The main thing I would ask of you is that if something doesn’t feel right, just stop,” Feheley said. “In the past, when things have gone wrong, I ask the performers about it and they always say ‘Yeah, something didn’t feel right.’ We don’t want anyone to get hurt. If I get hurt, that’s okay—I’m replaceable.”

One of the Rheinmaidens raised her hand with a question. “How are we going to do bathroom breaks?” she asked, gesturing to her elaborate costume. “There’s a lot of layers to these things.” (Feheley said they’d rehearse as long as possible, then take an extended break.)

Image: Lynn Lane

After climbing into the tanks, the Rheinmaidens splashed around, acclimating themselves to their new piscine environment. Before the rehearsal, the HGO technical team had used garden hoses to fill the three tanks with 300 gallons of water each, then dropped in heating coils to bring the water up to room temperature; the whole process takes about 40 minutes.

Finally, everything was ready. At a signal from the conductor, a pianist in the orchestra pit launched into the final bars of the opera’s famous prelude. On cue, the Rheinmaidens burst into song, gripping the sides of the tanks and projecting their voices to the back of the theater. In between vocal passages, they dove under water and struck various acrobatic poses. The central Rheinmaiden squirted the others with water from her fake breast.

A discordant piano chord suddenly interrupted the frivolity, signaling the entrance from stage right of the dwarf Alberich, sung by bearish English baritone Christopher Purves, whose costume—knee-high rubber waders, camouflage netting, and a Baby Bjorn–like bag around his chest—made him look like a cross between a Navy SEAL and the Gorton Fisherman. Purves shambled from tank to tank, trying to catch the Rheinmaidens as they mockingly eluded his grasp. When someone finally yelled cut, he turned to one of the assistant directors. “It just feels so unnatural,” he said. “I mean, if they’re over there, why the fuck am I over here?”

While the director mollified Purves, the costume designer jumped up on the platform and started repairing a tear in one of the Rheinmaidens’ costumes. The play’s Spanish director, Carlus Padrissa, stalked around the stage, filming everything with a videophone. Finally, everyone regrouped and began rehearsing the end of the scene, when the three tanks are lifted six feet into the air on steel cables, still bearing the Rheinmaidens, leaving Alberich flailing helplessly underneath. In the real production, during the scene’s climax, Purves will pull the plugs on the three tanks, draining all 900 gallons of water into a custom-designed catch basin beneath the stage and finally giving him access to his coveted gold.

For now, though, the Rheinmaidens were just trying to get used to the height, peering down doubtfully at the people below. The tanks swayed slightly in the air. Water lapped over the sides. In the orchestra pit, the conductor raised her arms, the pianist began to play, and, right on cue, the Rheinmaidens resumed singing.