At the CounterCurrent Festival, an Explosion of Art and Violins

Islamic Violins, Edition II

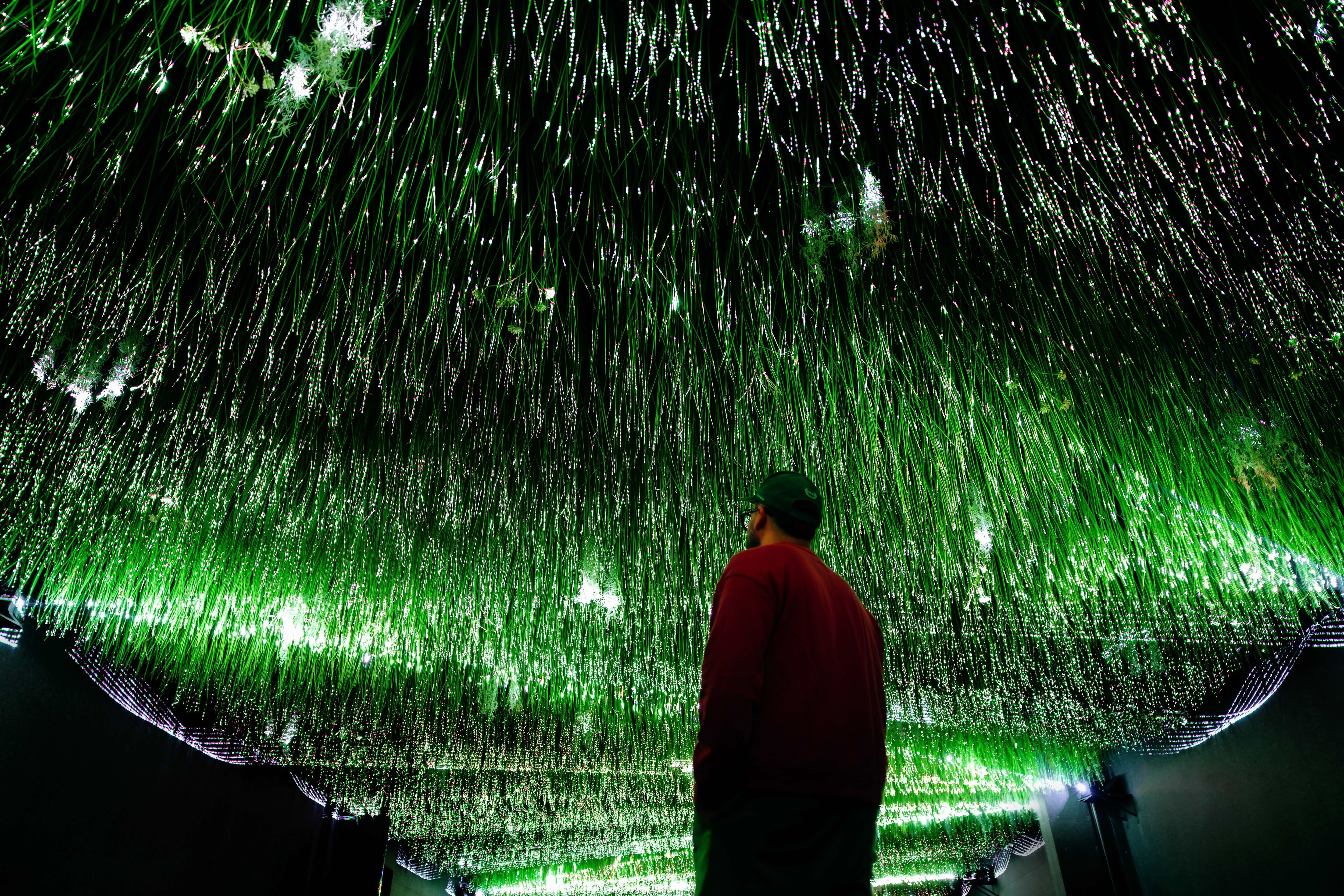

Image: Robert Kluijver

Every January, artists and art professionals from around the world descend on New York City for the annual conference of the Association of Performing Arts Presenters. Over the years, numerous smaller conferences and festivals have sprung up around the event, so arts presenters spend the week meeting artists, booking performances, and commissioning new works. It’s a bit like speed dating, said Karen Farber, the executive director of UH’s Cynthia Woods Mitchell Center for the Arts. In one popular event, presenters like Farber get precisely 10 minutes each with a selection of artists.

“It’s a pitch session, but a pitch session with completely visionary, experimental, interesting artists,” Farber said. “Usually after it’s finished the event dissolves into a lot of people sitting around tables, chatting with artists. A lot of programming happens right there.”

The result of all that pitching and dating can be seen at Houston’s second annual CounterCurrent Festival this month, six days of daring, cutting-edge performance art sponsored by the Mitchell Center. While the fest is headquartered at the FlexSpace gallery in Montrose, performances will take place at locations across the city, from Project Row Houses to 13 Celsius, the Midtown wine bar.

One of the festival’s nine featured works—or projects, as Farber prefers to call them—is Kenyan-born, Amsterdam- and Berlin-based multimedia artist Ibrahim Quraishi’s latest work in his series “Islamic Violins,” an art installation (and play on words) comprising approximately 20 used violins from Middle Eastern countries currently at war, including Syria, Afghanistan, and Iraq. Quraishi traveled around the Middle East acquiring the violins, had them shipped to his Berlin studio, and then fixed them up, applying polish, lacquer, and white paint, a process that took about five days per instrument. In the exhibition the identical white violins will dangle from the ceiling.

Violins, Quraishi said, originated in the Middle Ages in the Muslim culture of Central Asia but later became symbols of cosmopolitanism and sophistication in Europe, serving as a symbolic bridge between Islam and Christianity. Judaism too found a place for violins, but under the Third Reich Jews were prohibited from playing the instruments in public. Countries like Saudi Arabia also ban their playing, which violates Sharia law. “It has many levels of resonance,” Quraishi said. “It implicates ideas of sound, history, culture, values.”

The artist’s installation will include video of his first work in the series, in which Quraishi wired dozens of violins with explosives and timed them to blow up once an hour on the hour at a gallery in Vienna while spectators watched. “There were small pieces of Semtex I obtained for each violin—legally, of course. Security considerations and all that. It’s controlled, it’s artistic, but it is an explosive element. And you know, some people were shocked, others were laughing. Because it was in Vienna, some people thought I was making fun of Mozart!”

We couldn’t help but wonder: will there be any violence in his Houston installation? “There always is, isn’t there?” he said, grinning mischievously. “It’ll be a surprise.”

CounterCurrent Festival April 14–19. Free. Various locations. countercurrentfestival.org