Rachel Kushner Wants You to Understand What It's Like on the Inside

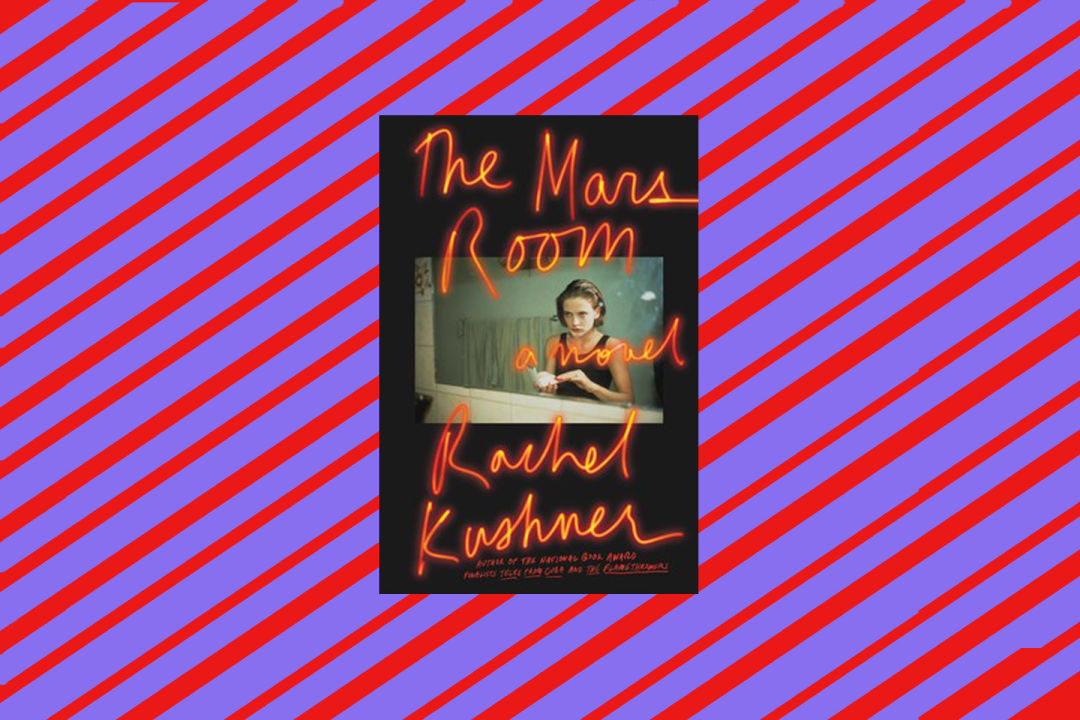

Image: Courtesy of Simon & Schuster

In her new novel The Mars Room, National Book Award finalist Rachel Kushner gives readers an inside look at prison life through Romy Hall, who’s been given two consecutive life sentences. As we learn more about Romy and the people who come into her orbit, Kushner presents a novelistic spin on the realities of life on the inside.

Kushner will speak at Palmer Memorial Episcopal Church about The Mars Room on May 24, an event sponsored by Brazos Bookstore. We caught up with her to talk about seeing yourself in literature, eau de Cell Block 64, and what book she’d want with her in prison.

What was the most shocking thing you discovered while researching prison life?

For some reason, it’s been hard for me to answer this question, which has not been an unpopular one. It’s a good question, and it’s logical. But before answering, I do want to say that not having been incarcerated myself, it would’ve been difficult to write about it without acquiring some familiarity with life on the inside and what it’s like for people, especially long-termers. But I don’t know if I would call the way I acquired it research. It is, in a sense. But let’s put it this way: I’m pretty involved with people in prison and the prison abolition movement, and in a certain way, I’m more involved with them now than I was when I was writing the book, simply because I have more room to take on other people’s lives now that I’m done imagining the full world that a novel requires. Because the people that have been really instrumental in terms of telling me what prison is like—because I’m very close to those people and talk to them all the time—they aren’t “research” for me. But I did learn a lot from them.

This is a very small thing, but I went on this tour, like undercover, with students who wanted to get jobs working as prison guards. We were on a bus for 10 days going to different men’s facilities, and then we went to a women’s facility that I kind of based my fictional prison on. And all of the prisons have the same smell. It’s this really strong oily, floral, very treacly fragrance. I asked this dude at Folsom—the original Folsom Prison, where Johnny Cash performed—I was in the cafeteria where Johnny Cash had played, and I started to notice that every facility had the same smell. I asked this guard, “What is that smell?” And he goes, “It’s Cell Block 64.” And I said, “Cell Block 64?” And he goes, “Yeah, that’s our state brand cleaner that we use.” That’s what they use, and that’s what it’s called. Apparently it can be quite poisonous.

At first, we just know the basics of Romy’s crime, but the novel forces us to reconsider her actions as it goes on and we learn more. Are there any figures in history or pop culture that you think deserve reconsideration?

Well, I didn’t mean to stress her as being worthy of reconsideration. But I’m glad you asked about this. Instead, I think that every individual is worthy of true and in-depth consideration. When people are convicted of a crime and go to prison, in a certain way they are effectively judged by the worst act they have ever committed, because that’s what ends up defining their lives. Especially if they get a life sentence. To people on the outside, middle class people who don’t have a lot of exposure to the criminal justice system and haven’t had their lives profoundly affected by it, they might just say, “That’s it for that person. They’ve committed harm, and this is the way they have to pay back society.” But for people who are in prison, or for people who are very involved with people in prison—like I am—you come to understand very quickly, by instinct alone and without it being explained to you, that people are complicated and nuanced and made up of multiple traits and features that don’t derive from this one act for which they were convicted.

So it wasn’t that Romy in particular is worthy of reconsideration, but more that I wanted to write what felt like a portrait of somebody who could believably be in the California prison system. And overwhelmingly, most people in that system have been convicted with what the state considers serious, violent felonies. And only a small percentage of those people are serving life. But I’m close to a lot of lifers, and I think about their lives. And I ask myself why they have to pay back the state with their life, no matter how long they live. Whether it’s four years or 40—that’s the segment of time by which they need to compensate the state for the harm they’ve committed. I’m interested in maybe standing with those people, because I still think that they’re human beings. I don’t mean to depict Romy in any way as relatively innocent—she’s guilty—but she’s still of interest to me.

One of the lines that I thought about a lot comes from Sammy, Romy’s cellmate. She’s describing how she and the other women are voraciously reading a Danielle Steel novel about prison, and she says, “You want to read about a world you know, not just ones you don’t know.” Why is it important for people to see themselves in literature?

That’s such a great question. I think it does speak to something true. People want to see themselves in literature. I was directly inspired by something a friend of mine told me, a formerly incarcerated person who was an advisor to me and is a close friend. She spent a lot of time in administrative segregation and a secure housing unit, and everybody was reading this Danielle Steel novel called Malice. And she still talks about that book! She said everybody was reading this book and it was about women in prison. And I thought, naïvely, “Gosh, why would you want to read that? Don’t you want to read something that would take you away from the reality of prison?” And she was like, “No!” That never even occurred to her. So I think there is something essential about seeing yourself in literature. I’ve noticed a teeny bit that there’s this kind of middle class perception that literature is just for middle class people. Like, “Why should we read about people in prison?” And there’s a pretty big presumption in the use of that we. But maybe books about poor people and people whose lives have been affected by the criminal justice system are also for them.

If you had to have one book with you in prison, what book would you want to have with you?

That’s a tough one. Just one book? I would say Proust’s In Search of Lost Time, because that would give me seven volumes to read. But it would kind of be strange to read Proust in prison. So since prison is such an American phenomenon—at least to me—I would probably choose Moby-Dick by Herman Melville, which is such an American book. It has such a richness to it that is almost biblical. The other book I would choose would be the Old Testament, because you can get a copy of that in prison.

And I feel like the Old Testament and Moby-Dick kind of go hand in hand, too.

That was my thought!

Rachel Kushner, May 24 at 7:30 p.m. Tickets $27 (book included). Palmer Memorial Episcopal Church, 6221 Main Street. More information and tickets at brazosbookstore.com.