Marlon James on Mythology, Writing Sex, and Decolonizing Fantasy Literature

Marlon James is about to have a big year.

His newest novel, Black Leopard, Red Wolf, has drawn advance praise from major media outlets and other writers of serious sci-fi and fantasy fiction such as Neil Gaiman, Victor LaValle, and Jeff VanderMeer.

Not that James needed the praise to get this book off the ground. He won the Man Booker Prize in 2015 for his novel A Brief History of Seven Killings, an accolade that grants most writers carte blanche to write whatever kind of book they want. But instead of following up his prize-winner with “a small, mature, realistic novel set in the Bronx or something,” James decided to go huge: Black Leopard, Red Wolf is the first installment in a planned trilogy that he’s described as an “African Game of Thrones,” inspired by his love of mythology and big books.

On Sunday, Feb. 10, James will speak in Houston about his latest book. We caught up with James to talk about his call with George R.R. Martin, why all good sex is gratuitous, and who’s telling the truth in Black Leopard, Red Wolf.

Who came up with the phrase “African Game of Thrones”?

I came up with it as a joke! Not toward George (R.R. Martin), because I have a lot of love and respect for George. I love how he dared to put these things that we tend to assign to a certain age group into decidedly adult fiction. I think that’s fantastic. But I sent this description with the phrase “African Game of Thrones” to this magazine thinking, “OK, not many people will read it.” But it turns out that everybody who reads a magazine works in media. And then it took off. I don’t mind, if it makes people pay attention. Even George ended up calling me.

Oh my gosh. What was that like?

He said, “I heard you’re working on an African take on my novel. That’s so exciting.”

That’s a pretty good compliment!

It is a pretty good compliment. He is the grandmaster. But yeah, that’s the thing. The things you work hard to make go viral never get noticed, and the things you say offhand—that’s what catches on.

How long has the idea for this story been in your head?

I’m a huge, huge, huge student and fan of mythology—all of it. I can speak as much about Norse and Greek mythology as much as I can speak about African mythology. By the time the Booker Prize came around, I had already been imagining and jotting down notes on this for a good three months. My problem is that I get easily bored. I’ve never been interested in writing the same thing twice, or even revisiting the same character twice. My favorite novels, whether they’re fantasy or not, are sumptuous feasts of novels: novels that are big, novels that are almost too much, novels that carry a whole variety of stuff. Song of Solomon, Midnight’s Children, My Name is Red, the Arabian Nights, Don Quixote—stuff that’s big and ambitious, confusing, maddening, and head-scratching, where the reader has to do some work, but is hopefully rewarded. I wanted to write one of those, because those are the books I’ve always loved. I remember growing up and not having a lot of books and not having a lot of choice, so I would always pick the big book. I’d get more out of it and spend more time with it. I didn’t know when the next book was coming, so of course I’m going to grab the big one.

I agree with you about Song of Solomon, too. I read it last year and it was one of my favorites. But I was just like, how does she do this every time she writes a book? This book is so old, and I’m still on the edge of my seat trying to figure it out, and I’m so nervous and stressed out. And it’s beautiful, too.

To me, the first 200 or so pages is just the best novel I’ve ever read. But man, the last 50 pages of that novel, I’m amazed it happened. I just don’t know how she did it. I read it standing up, and I was on a balcony, which is just a bad idea. (Laughs.) Because I so believed that Milkman flew at the end. Spoiler alert to all the readers. I so believed he flew at the end that I was about to jump off the balcony, too. And I’m not even joking about the balcony! I was like, “So this is what great writing is.”

A lot of fantasy books can feel kind of sterile and sexless, but in this book it feels like everyone and everything is having sex, with no real hang-ups—anything that we might perceive as queer feels pretty normal in the world of the book. How important was it for you to make that a part of Black Leopard, Red Wolf?

The thing about our fantasy canon and the older books is that they’re all great, but they’re all suffused with a kind of Christianity. And that’s fine! We take our myths where we can get them. But that sort of morality, piousness, sexlessness is not anything that has to do with Africa. It doesn’t have anything to do with ancient Greece, either, if you’re reading Greek myths. Greek mythology and African mythology and all the ancient stories are suffused with eroticism, and why wouldn’t they be? That is one of the great human impulses. There was a lot of European-ness I had to excise from myself to write this book: veiled biblical epics and the chaste princess and the noble but sexless hero. That’s just not how it is. It’s suffused with an eroticism, and it’s an eroticism that everyone sees as so natural that they’re already over it.

It was definitely refreshing. When you think of something like The Lord of the Rings where people are descended from these great families and everyone has a bunch of children—there’s a dissonance because I don’t believe anyone is having sex, ever.

(Laughs.) Yeah! I think sometimes writers in the Western tradition worry that they’re going to slip into pornography. And I can understand that. It’s something that people are super scared of, which says a lot more about how we’re still processing sexuality in the world than anything about the stories themselves.

The world the book is set in is so inventive and wild—I felt like you conjured more unique imagery in the first chapter than I normally see in a year’s worth of reading. Was there anything that felt too outlandish to include?

There were one or two things—like my shape-shifting hyenas—where I was like Oh my God, I can’t even read this twice. But I’m a believer in staying true to the story. And I’m not writing something European and using those standards for what’s admissible and what’s not. It’s amazing sometimes, because you come across people saying kind of Puritan things like, “If you show desire and romance, you never have to show the sex.” Where does that ridiculous sort of view come from? And I think, “Why is it a matter of have to?” People will say it’s gratuitous sex, but all good sex is gratuitous. Otherwise you’re just having duty sex. (Laughs.) In the African myths, a lot of times it’s fun, sometimes it’s just sex, but there’s a refreshing sort of perspective on sex that I thought was really interesting. It’s funny, because we think of it as modern, but it’s actually really ancient. The stuff in the book about queerness and gender identity and plural pronouns—none of this is new. It’s great that we’re using “they” and “them,” but Africans have been doing this for thousands of years. But the fact is that I grew up in the West and I speak English, so a lot of it I discovered. That is stuff I found in research. It’s not me trying to score an intersectionality point, it’s research! And to find that there has always been a very rich queer tradition in Africa surprised me. There are lots of preachers in Africa who will tell you different, but they’re working from what they got from white American preachers.

There’s a lot of back and forth in the book about truth versus story. As a storyteller, how do you reckon with the balance between those two?

I reckon with it by getting rid of it. The whole idea of the authentic version, the director’s cut, the authorized biography: That’s not how people on the African continent process story. The truth is something you figure out. You have to do the detective work. That’s one of the things that came over to the Americas—the Br’er Rabbit stories, the Anansi stories, which are African. Anansi’s a trickster, but he’s also telling a story. So we already know we’re in the hands of an unreliable narrator. But that’s fine. When you’re here for the story, you already know there’s a possibility that this is a lie. So truth now comes from me listening and deciding if it’s truth or not. It doesn’t come from me saying something with a level of authority. That’s what I had to understand when I was writing this book. Which is why part two of the book is not picking up where part one left off: It’s a different character telling you a totally different version of the same story. And part three will be another person telling you a totally different version of the very same story. I’m sure readers will be bombarding me—maybe I’ll auction it off in 20 years’ time—but I’m not telling people who’s telling the truth. They’re going to have to decide. The reader’s going to have to pick. And it’s going to be interesting to watch them pick, because I’m definitely not telling who’s telling the truth.

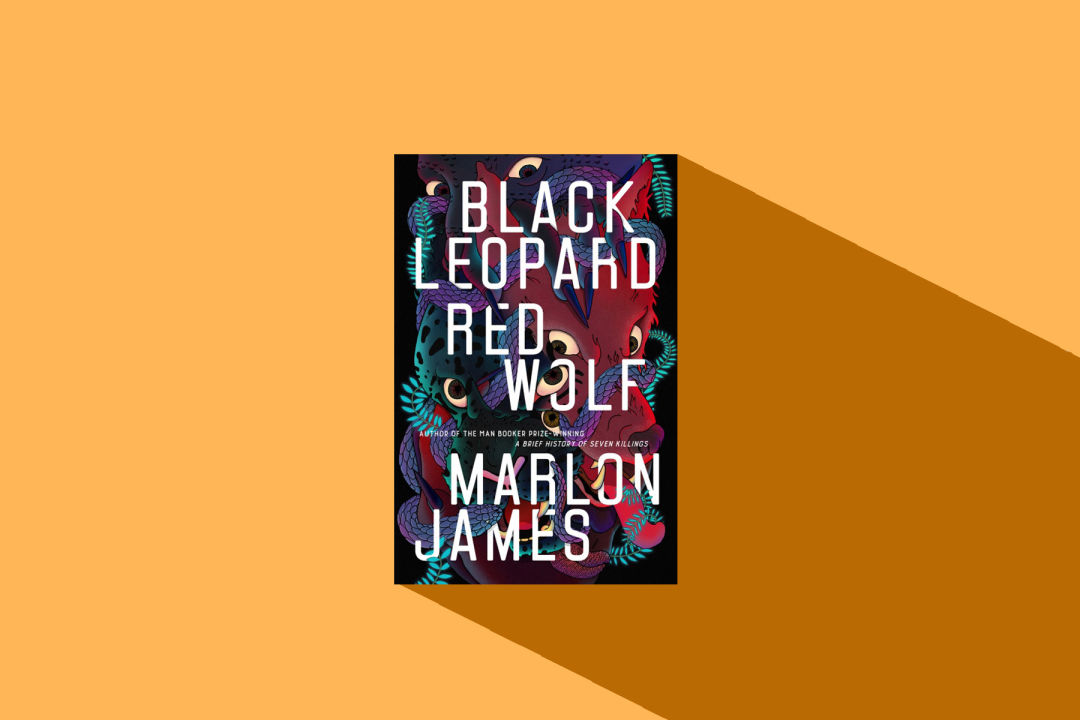

This book is one of the nicest galleys I’ve ever received—the cover is gorgeous already, but the velvet slipcover was beyond. What was your reaction to seeing the cover art for the first time?

(Laughs.) I think I screamed? It’s not what I was expecting at all. But I instantly saw it and loved it. It looked like a tattoo to me. I thought it was instantly fresh and captured what I was aiming for. It’s also very sort of comic book-y. I like that. I like the graphic novel tattoo kind of thing. I was like, “I’m going to have to resist the urge to tattoo this.”

Feb. 10. Tickets from $30 (book included). Palmer Memorial Episcopal Church, 6221 Main St. 713-523-0701. More info and tickets at brazosbookstore.com.