Danez Smith on Finding Joy, Cruelty, and Toni Braxton

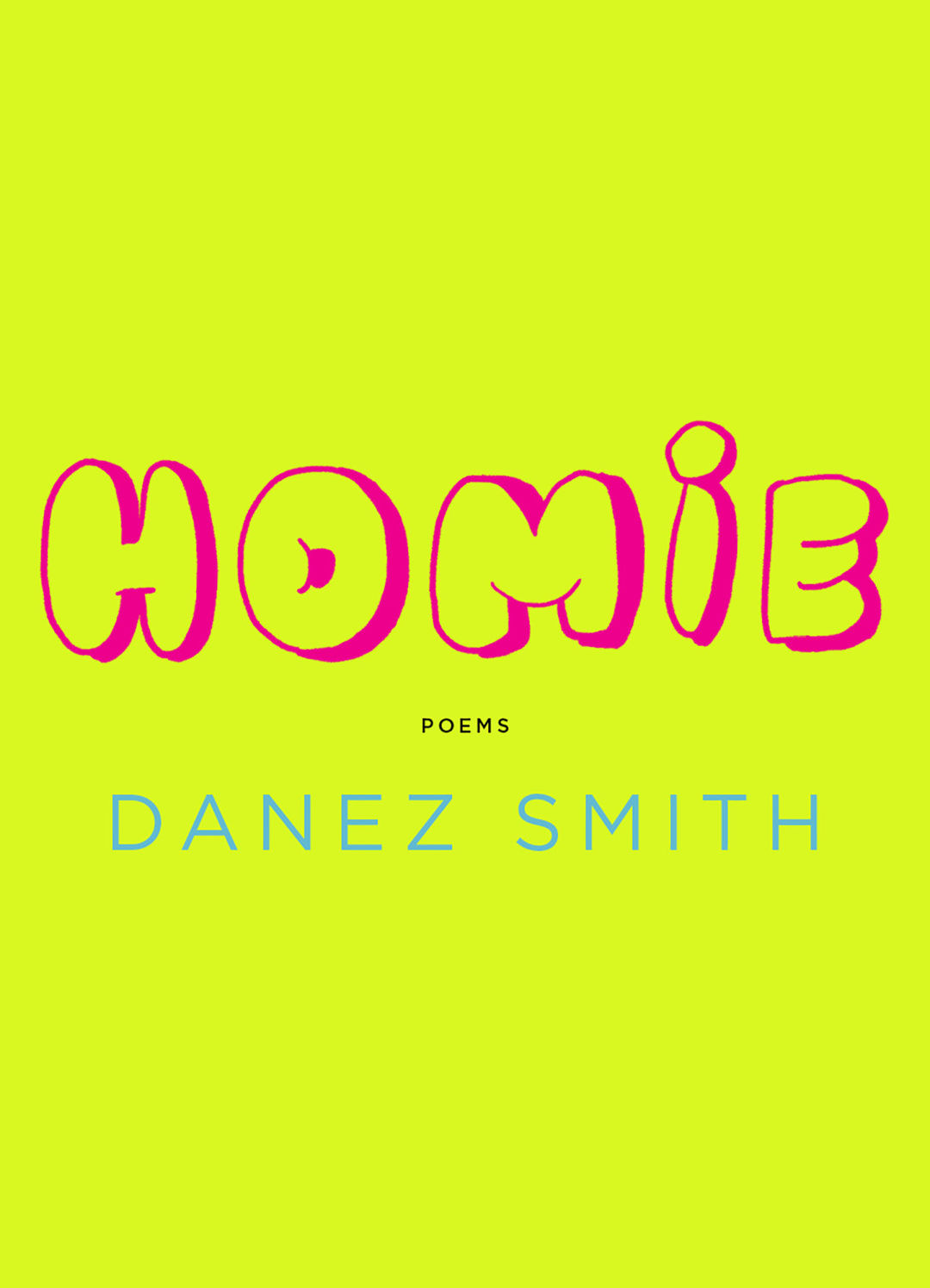

Image: Courtesy of Graywolf Press

When following up the success of their previous collection—2017’s National Book Award for Poetry finalist Don’t Call Us Dead—Danez Smith said the one thing they had to do was make joy feel abundant again and to trust in that joy. The result is Homie, Smith’s brand-new collection of poems from Graywolf Press. In it, Smith finds how joy can be both a salve for pain and a source of pleasure.

Smith will read from Homie with fellow poet Tarfia Faizullah at Brazos Bookstore on Friday, Jan 31. We caught up with Smith to talk about divas, Homie, and the nonexistent death of poetry before their visit to Houston.

You keep everyone on their toes by changing up your display name pretty regularly on Twitter. Can you tell me a little bit about the art behind that?

(Laughs.) I don’t think there’s any art behind it at all. I think you probably notice a pattern: most of them are black, female R&B singers from the ‘90s, ‘80s, ‘70s. I really like that music, and sometimes, in my head and in my house, I imagine myself as a walking, living diva, à la the Mariah Careys, and Toni Braxtons, and Patti LaBelles of the world. So, it’s just fun. I don’t think it’s artful or intentional, and it damn well might not be funny to anybody else but me.

Those women hold a lot of power and grace and swag—which is a word that I think has been dead since 2011. (Laughs.) But I love them, and I envy them, and I want to be them in my next life. I think the reason for that and Twitter titles is trying to do something like the poem “self-portrait as ‘90s R&B video” is doing in the book. As a genderqueer motherf**ker, I think a great joy of my life, whether as a child or as an adult, has been putting on something very feminine and fancy and walking around my house pretending to be Toni Braxton or Beyoncé. The Twitter thing is like a little version of that: my own little fantasies of the divas that I would wish to be.

What was it like putting together this collection after the success of Don’t Call Us Dead?

Horrible! For real. I think it was hard because Don’t Call Us Dead was so successful. So, there’s a lot of pressure, and not even pressure from everybody else, but myself and the ego that I have. There was a lot of pressure on each poem and I had a really intense period of writer’s block related to that. I just couldn’t write because I was too worried about everything else that wasn’t the actual poems and what they were saying. It took a while to recalibrate and remind myself that I was writing these poems out of an urgency and a need for myself—something that I wanted to communicate to myself and to other folks and not because of some award or social capital or success. Once I moved past that, the poems were great to write. It’s a book about friends and love and intimacy—and other things within that—and then I got to have fun with it, after I cleared my own bullsh*t.

One of poems that struck me the most in Homie was “rose,” an ode to a girl from your childhood. What was it like to reach back into the past for that particular poem?

I think a large project of mine is always diving back into memory and trying to recalibrate some of the violences that either I experienced, or I committed. For that poem, that’s something I’ve been trying to write for a very long time—maybe since when I first started writing poems at 14. Rose is somebody who’s always been on my mind. I’ve always sort of replayed the cruelties I committed in my mind over and over again, even if they were small, or if they were large, or communal. I think poems offer a good service to that because otherwise I’d be left to sit in my own shame of—like, I’m human and definitely have been evil at times—whereas the poem allows something more productive to happen. I’m not just wallowing in that, but hopefully in writing that poem I can help other folks either investigate the ways that they have been tiny and evil in their lives or to help folks heal from the trauma of being bullied.

In “my poems,” you say, “my mentor said once a poem can be whatever you want it to be.” What is most exciting to you about working in the form of poetry?

There’s this idea that pops up every couple of years that poetry is dead, or that nobody’s reading it, which I know to be a lie. But what does it mean to be a popular poet? Who gives a f***? I can do what I want. And I think that’s what’s most exciting to me about poetry. I love poetry. And I think to me, poetry as far as literary genres feels like the one where there’s the most room to play. Who can even say what a poem is when there are so many poems that look so many different ways? They move and operate and affect us in so many different ways. The longer I live within poetry, and write, and read, and love poetry, the more I don’t get what exactly a poem is. And that field of possibility in the genre just makes me so happy. That is a freedom I love and feel delivered by.

Jan. 31 Brazos Bookstore, 2421 Bissonett Street. More info at brazosbookstore.com

[This interview has been edited for length and clarity]