4 African American Artists Who Significantly Shaped Houston

From politicians like Barbara Jordan to sports heroes like UH alum Carl Lewis, Houston's Black community has been at the core of the city's existence from the very beginnings. They've played a major role in its religious heart, its massive food scene, and, of course, its arts community. As we near the end of Black History Month, we've put together a short list of creatives who significantly shaped Houston’s artistic landscape.

Portrait of Arnett Cobb, Downbeat, New York, N.Y., between 1946 and 1948

Arnett Cobb (1918-1989)

When he picked up a saxophone at Houston’s Wheatley High School, Arnett Cobb might not have set out to create a new sound, but he did. Cobb, along with a few others, originated the “Texas tenor” style, a robust, honking, bar-walking saxophone sound that had an element of swing and was steeped in the blues.

Cobb was still in his teens when he became a founding member of the landmark Milt Larkin Orchestra in 1936—one of the most successful touring bands of the time. After he left Larkin’s group in 1942, he resisted invitations from Jimmie Lunceford and Count Basie, among others, to join their orchestras, opting instead to work with Lionel Hampton until he formed his own group in 1947.

“When he was with Milt Larkin, that was a family,” says Lizette Cobb, Arnett’s daughter and former manager. “He wanted that with any other band he joined. Other bands were organizations, not families. He knew the difference.”

In addition to writing and recording several hits, including “Smooth Sailing” (Ella Fitzgerald’s signature scat), Cobb, who won a Grammy with B.B. King, supported such artists as Dinah Washington, Jackie Wilson, and comedian Redd Foxx over the years, He made a young James Brown his opening act, helping to launch the singer’s career. After a near-fatal car accident in 1956 left him permanently on crutches, Cobb, returned to Houston, where he managed Club Ebony and organized tours for acts including Sammy Davis, Sarah Vaughn, Ella Fitzgerald, and Ray Charles.

“I can clearly hear his influence on other people who are playing today,” Lizette Cobb says. “Some, like Shelley Carrol, it’s very clear; others it’s less obvious, but it’s there.”

Conrad Johnson (1915-2008)

Under the direction of Conrad Johnson, the Kashmere High School Stage Band did much more than many professional groups. They won 42 out of the 46 band contests between 1969 and 1977; toured throughout the U.S., Asia, and Europe; and recorded eight albums—while all its musicians were still in high school.

Johnson started off as a musician, learning saxophone and clarinet while at Houston’s Jack Yates High School, where his father was the bandleader. After graduating from college, he wrote and produced blues tunes for Freedom Records and performed with other young Texas jazz musicians, including Illinois Jacquet, Leon Spencer, and Melvin Sparks.

Johnson began his teaching career in 1941. Because the school lacked classroom space, he taught marching band in an old Chevrolet bus. He joined the staff at Kashmere High School in 1969.

During his time as Kashmere’s band, Johnson earned the nickname “Prof” because he insisted all his students learn to read music and adhere to strict professional standards. The effort paid off. Kashmere High School Stage Band built an international reputation for solid musicianship and dynamic, show-stopping performances that melded elements of soul funk music with big-band jazz.

In 1972, the group, by then also known as “The Thunder Soul,” won Best Stage Band in the Nation honors at the All-American High School Stage Band Festival. Johnson, who retired from Kashmere in 1978, would go on to be inducted into the Texas Bandmasters Hall of Fame. His story was later immortalized in a 2010 documentary produced by Jamie Foxx.

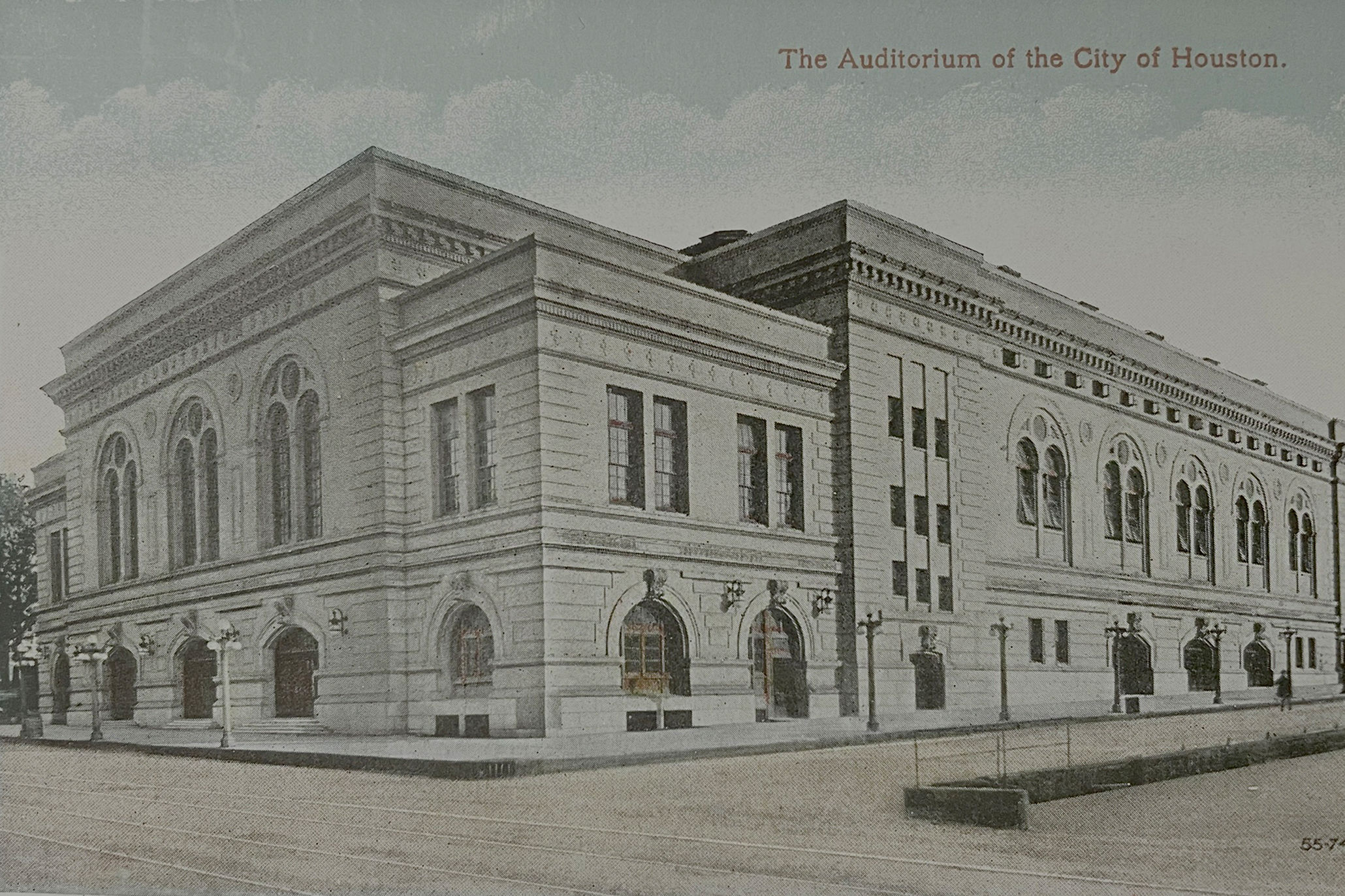

George W. Hawkins

George W. Hawkins (1947-1990)

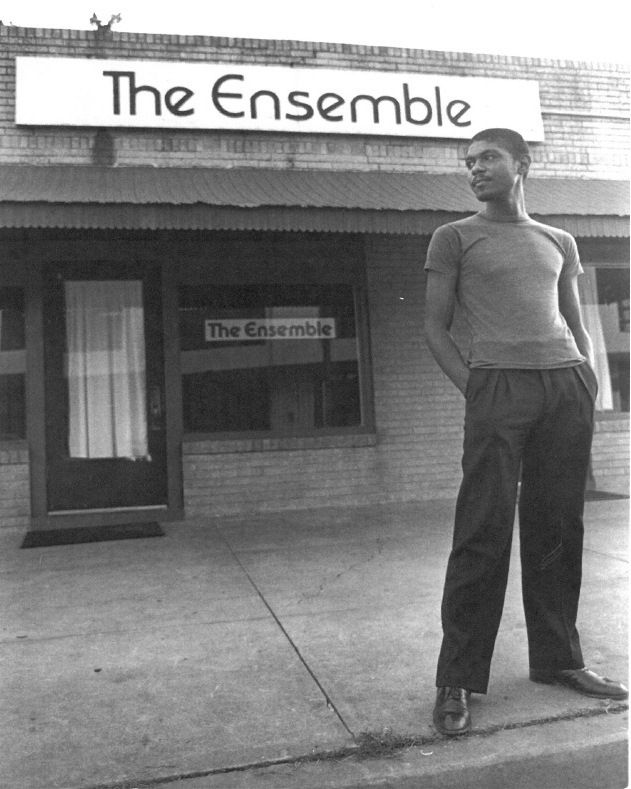

Frustrated by the lack of roles for African Americans in Houston theater productions, Hawkins decided to start his own company, the Black Ensemble Theatre. At first a touring company—a loose term to describe how Hawkins would pack his Cadillac with props and costumes and drive around the city performing in borrowed and appropriated spaces—Hawkins’ company found a permeant home on Taum Street and began mounting full productions.

The company, which would eventually shorten its name to The Ensemble Theatre, moved to a larger space on Main Street, where it has grown exponentially. Now the oldest African American theater company in the Southwest, The Ensemble stages a full slate of productions relating to the African American experience while also running a touring educational and artist residency program. If that's not enough, the company also hires around 200 artists each year.

“It seemed impossible,” Artistic Director Eileen J. Morris says. “But George kept saying we could do it, and we did.”

Don Robey (1903-1975)

Before launching Peacock and, later, Duke Records, Don Robey opened Houston's Bronze Peacock Dinner Club in 1945 and booked jazz and R&B acts there. Those shows led to his future success. As the story goes, one night, guitarist T-Bone Walker had to leave the stage during a performance, and a young man jumped up from out of the audience to take his place. That young guitarist was Clarence “Gatemouth” Brown, and when Robey started Peacock Records in 1947, Brown was the first artist he signed. When Robey took Duke Records over in 1953, his slate of artists—which for a time featured Big Mama Thornton, The Dixie Hummingbirds, and Little Richard—grew to include Bobby “Blue” Bland.

It was Robey who produced Thornton’s “Hound Dog” in 1953, a tune that was later made famous by Elvis Presley. At the height of his success, Robey, who has been accused of unfairly obtaining the rights to many songs that recorded on his labels, had more than a hundred artists under contract.

And Peacock Records also preceded Berry Gordy’s Motown by 12 years.

“Not to take any shine off of Motown, but Peacock and Duke Records did what Motown did,” Lizette Cobb says (her father was a contemporary of Robey). “But they did it first, and they did it in the South.”