Lidia Yuknavitch Talks New Book Ahead of Brazos Reading

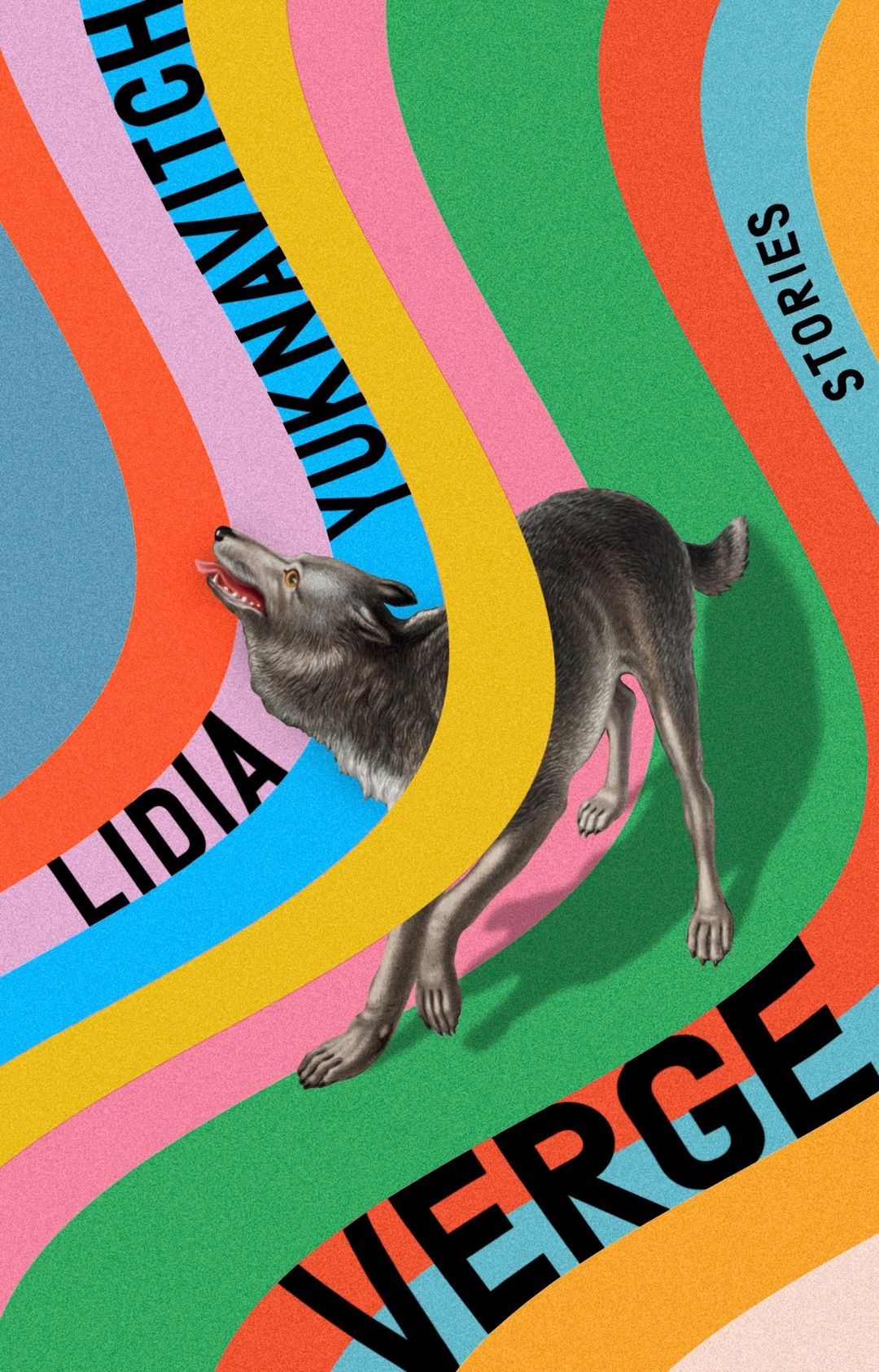

Image: Courtesy of Riverhead Books

Lidia Yuknavitch is best known for her explosive novels, her cult-favorite memoir, and her uplifting TED Talk. So her newest book, Verge, represents something of a divergence: It’s her first collection of short fiction.

Verge, which was released earlier this month, features a multitude of characters on the brink—people at the edge of acting on unspeakable desires, taking new paths in their lives, and uncovering hidden knowledge.

Yuknavitch will read from Verge at Brazos Bookstore on Wednesday, Feb 12. We caught up with her to talk about her brand new short story collection before she visits Houston.

In one of Verge’s stories, “Cusp,” the narrator says that “books continued to house me in a way that the world did not.” What books do that for you?

In some ways, all of them. Once I’m inside some type of art environment, all the stories I’ve been carrying about who I’m supposed to be or how I’ve f**ked it up fall away. And I can be free flowing again, without borders or limits. So, in a way, it’s all books: I can read a crappy book and feel better than I would walking outside my house and trying to navigate the world. I’m just not very good at it. And I’m not very good at being a person in the world. But I’m very, very good at sitting inside a painting or inside a story, or poem, or music, or performance. That world makes more sense to me. But, you know, we can’t live in those worlds. But I’ve also had times in my life where I’ve entered for real psychosis or depression or grief that made you immobilized.

Those worlds, like the imagination and like the dreamscape, have something to show us about how we’re behaving in this world everybody else calls real. In some ways, I’m in the universe to remind everybody that there are other worlds that are real places where we can learn how to treat each other differently and see differently. So, stories are one of those worlds.

As you edited and put this collection together, were there any parallels or contrasts between the stories that jumped out to you that you hadn’t noticed at first?

Oh, yeah. This happens to me with novels, too. I write novels in fragments or pieces, and then I wait for the pattern to show up before I try any arrangement, if that makes sense. Similarly, with these stories, if you put them on the floor and move them around, you start to see echo effects, patterns, and even tensions, little fistfights with each other. I myself didn’t come up with the order alone in a vacuum. We came up with the order as an editorial team. But they are definitely meant to have a relationship with each other. It’s not like a novel in stories—which is also an interesting thing—but they are meant to crisscross and echo each other, and interrogate each other, and make loop-de-loops around each other.

A phrase from the first story in the collection, “The Pull,” really jumped out to me. It’s a story about swimming, then it transcends beyond swimming and becomes a story about immigration. The phrase “violent compassion” really struck me. What about that phrase felt right for you in that story?

Well, the big, overdramatic thing to say about it is that has been my life. And it has an origin point probably around a sad thing: My daughter died the day she was born. So, I was faced with this moment of both 'excruciating, brutal grief and pain' and 'I’ve never loved anything more beautiful in my life,' which are supposed to be opposites. And in my life forever after, they were not. That origin point is probably when I started to become a writer.

So that marked my experience and my entrance into storytelling, like, Oh, binaries are a lie! (Laughs.) When I was doing my orals, getting my Ph.D., I was asked about that—the distance between the beautiful and grotesque—and I was instantly able to say that they were two sides of the same moment. And literature all the time is bringing us a version of that. But in these stories, in particular, I’m attempting to hold the binaries open, and to move toward the thing people might think of as too much or difficult or even grotesque or painful and just hold it open and let it shiver; let it vibrate a little bit, without resolving, to make us see it and see if there’s anything in there worth thinking about.

Lidia Yuknavitch, Feb 12 at 6:30 p.m. Brazos Bookstore, 2421 Bissonett St. More information at brazosbookstore.com.