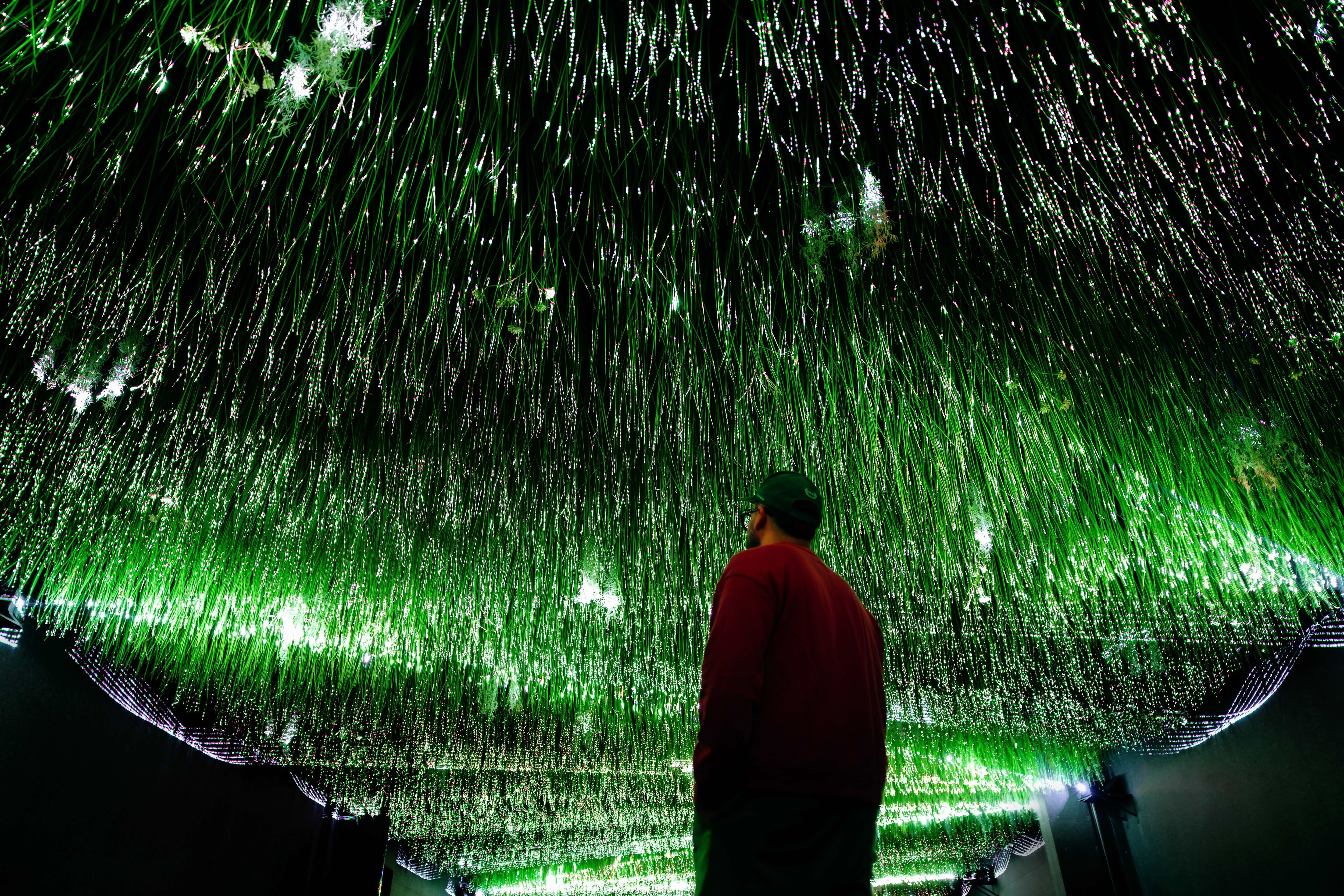

Houston Is Home to a Prolific New Yorker Cartoonist

Image: Courtesy Mary Lawton

For 30 years, Houston-based cartoonist Mary Lawton submitted her work to The New Yorker. For 30 years, she received a series of rejection notices, most of them quite polite but with the same gist: thanks, but no thanks. Occasionally the rejections came with a nice note: “I’m sorry.” She took this as an encouraging sign that they’d actually read it.

“It’s like trying to get on The Tonight Show if you’re a comedian,” she said recently over coffee in the Heights. “It’s the top. I just kept plugging along, doing it my own way.”

Then, in 2017, the magazine hired a new cartoon editor, Emma Allen, the first woman to hold that job. There had been female cartoonists at The New Yorker—most notably Roz Chast, deadpan observer of modern neuroses—but never in the gatekeeper post. Lawton, who moved to Houston in 1994, had all but given up on the magazine. But she saw a possible opening with the infusion of new blood at a publication that has long battled a reputation for stodginess. She submitted once more. This time, she got something for which she wasn’t prepared: a yes.

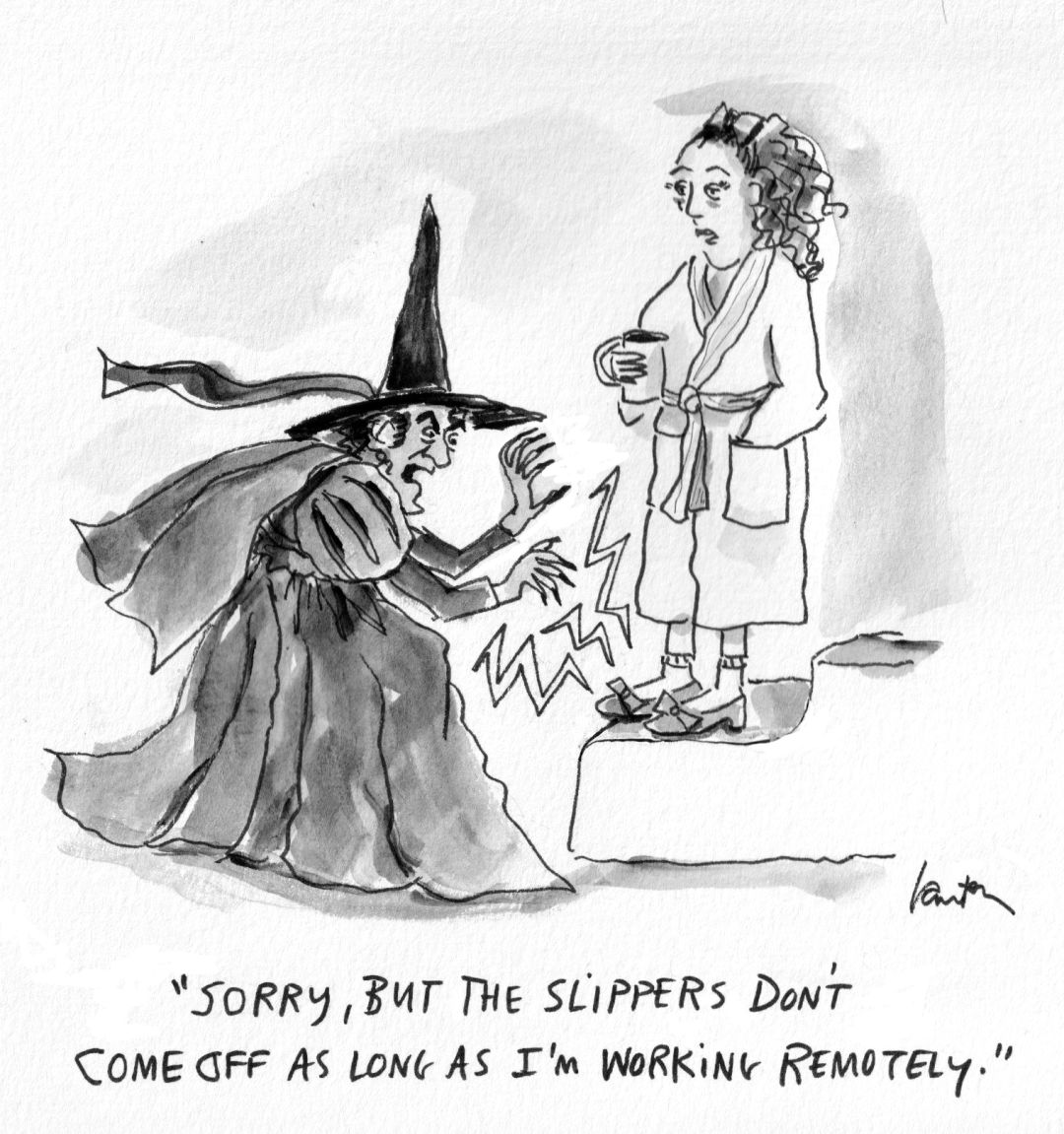

Image: Courtesy Mary Lawton

“I just wanted to sing and dance, it was a really wonderful feeling,” she says, but it was followed almost immediately by a case of imposter syndrome. The thoughts plagued her: “Well, it’s only because the new editor is a woman. I don’t really belong here.” Then they bought another cartoon. And another. It took about 15 appearances in the magazine’s hallowed pages before the realization hit her: “I’m in.”

According to Allen, Lawton should have never doubted herself. “Her characters are so hysterical and unique,” the editor said via email. “Each person or animal that populates her gags has such a richly drawn personality that you can almost imagine them strolling off the page back into their zany lives. And you’d be tempted to follow them to see what silliness ensues.”

The cartoon that gained her entry shows a section of airline passengers sitting in two-seat rows, some eyeing each other askance, others staring into the middle distance. The caption: “Passengers, as we begin our descent you may now suddenly act open and friendly to the person beside you.” The cartoon exudes a sense of droll universality, a hallmark of Lawton’s work.

Image: Courtesy Mary Lawton

Elsewhere, she works with absurdist wordplay. A piece captioned “Bully in a china shop” shows a tough customer harassing a bespectacled store clerk: “Gimme the Limoges tea set, punk.” (“She may boast the claim to fame of being the only cartoonist ever to make a Limoges china joke in our pages,” Allen says.) Lawton’s work also stays plugged into current events, which she showed with a spate of cartoons dealing with the COVID-19 outbreak, recently on display at the G Spot, the gallery owned by the late Houston artist Wayne Gilbert. One of these cartoons shows a throng of revelers crowded around a Thanksgiving dinner as COVID-19 spores linger all around. The caption: “Lovely spread!”

Born in 1958 on Long Island, the youngest of six siblings, Lawton grew up infatuated with her older brother’s Mad Magazine collection. “It just struck me as really outside the box,” she says. “Although I was terrified of Alfred E. Neuman. I think I just always felt irreverent and not mainstream. I never really loved the straightforward, syndicated cartoons. That wasn’t my interest at all.” In 1979 Lawton moved to Boston, where she fell in with a group of fellow alternative cartoonists. Lynda Barry and Matt Groening, many years before The Simpsons, were among her heroes. So was Bostonian William Steig, who became a mentor and a sort of father figure for Lawton. Best known for creating the Shrek character (long before the ogre became a movie star), Steig encouraged Lawton to keep drawing and keep working.

Image: Courtesy Mary Lawton

In Boston, Lawton worked as a cook, and met her husband, a geneticist who specializes in eye disease. She took photography and cartooning courses at Massachusetts College of Art and Design. They moved to Berkeley for his postdoc work, and then to Houston for his biology professor job at Baylor University. All the while she cartooned, getting her work accepted here and there, keeping her eyes on the prize. Then, with the New Yorker breakthrough, the floodgates opened. Her work continues to run in the magazine, and she’s also now a member of Six Chix, a collective of six female cartoonists whose collaborative strip is distributed by King Features Syndicate.

Lawton broke through at a prime time to be a cartoonist, if not a great moment for the republic. Between Covid and Donald Trump, there was no shortage of material. “There were all the hilarious things that he kept on doing, and the out-of-this-world things that kept happening,” she says. “Much of what I did every day was out of horror and disbelief. I thought I’d better keep on putting stuff out there because this is not normal. And if I don’t keep on showing that this is not normal, it’ll become normal.”

You can find and purchase Lawton’s work on the Curated Cartoons website. But she also keeps an album of her rejection notices. Weighing in at more than four pounds, it includes everything from brief form notes to “beautiful handwritten letters” from Aline Kominsky-Crumb, the late underground cartoonist, wife of Robert Crumb, and a founding member of the Wimmen’s Comix collective. Now on the top rung of the ladder, Lawton still likes to be reminded of when she struggled to get a leg up.