This Makerspace for Photography Is the Only One of Its Kind in Houston

Jessi Bowman launched the photo lab portion of Flats after realizing there was a shortage of community-focused photography spaces in Houston.

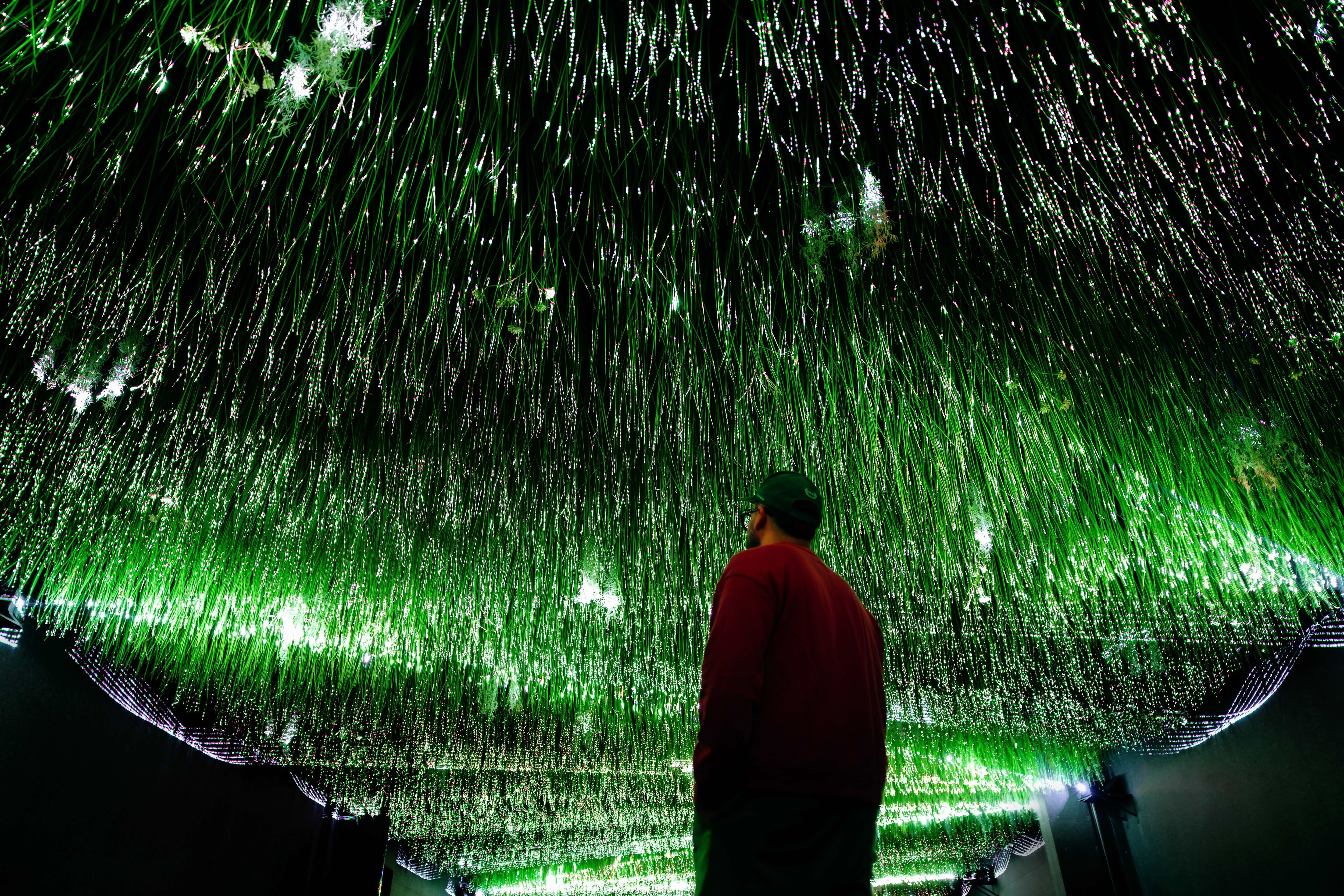

Image: Courtesy Nneoma Ajiwe

Jessi Bowman still has the light-pink Barbie camera she was given as a gift when she was six years old. Today, the treasured ‘90s collectible, which uses hard-to-find 110 film, sits on a special shelf in Texas-born Bowman’s apartment, sandwiched between a 1980s Polaroid camera that was formerly used for taking passport photos and a 1960s Super 8 film camera that’s no longer in working condition. It should come as a surprise to no one that someone with such a collection of film ephemera is in the photography business.

Now, many years after her cherished Barbie camera turned from plaything to display object, Bowman runs Flats, a budding Houston business dedicated to all things photography. Started in 2016 as a nomadic photography exhibition series, Flats has evolved into a photo lab that also offers photo-developing services. Sponsored by Fresh Arts and funded in part through the city’s Houston Arts Alliance, it’s home to the only community darkroom space in Houston.

Flats was originally launched in 2016 as a nomadic photography exhibition series that would hold shows from time to time in people's homes.

Image: Courtesy Jessi Bowman

In the beginning, Bowman, who has degrees in art history and photography, and was previously an exhibitions manager for the Houston Center for Photography, ran the photo lab from her apartment—sans the public darkroom and helpful nonprofit funding. “I Airbnb’d out my guest bedroom, I walked dogs, I did all these things part-time until I could get into a space,” she says, noting that she decided to open the photo lab after realizing there was a deficit in community-focused photography spaces in Houston.

In early 2020, just two weeks before the pandemic hit, and six months after first opening the space inside her apartment, Bowman finally acquired the funds to move Flats into the upstairs suite of a building in Montrose, just a couple of doors down from the Magick Cauldron.

In early 2020, Bowman moved Flats to its current home in Montrose. There's a 24-hour drop-off box by the front door where clients can deposit film they need developed.

Image: Courtesy Jessi Bowman

The timing of the space’s opening in the midst of the pandemic ended up being fortuitous in many ways. Due to canceled exhibitions, Bowman was able to slow down and focus more of her efforts on honing her services—from the film-developing aspect to the addition of the community darkroom. “Everybody was looking for a hobby at the time,” she says, “so that really helped this whole side of things.” Although the cozy space has several rooms, Bowman didn’t use all of them initially. Instead, she rented some out to other artists. About a year later, her business grew enough that she was able to take over the entire unit.

Today, Bowman, who started out running things solo, has three employees, and every room in the suite is dedicated in some way to the art of photography. There’s a cheerful entry area that houses a desk and a table, a mélange of photographs plastered joyfully across its walls. A retro vending machine by the front door filled with rolls of film adds a kitschy touch to the room. One area functions as a classroom for the variety of workshops Flats hosts, while another room down the hallway is used for developing film. A large film machine holds court in the middle, and in one corner you’ll usually see several rolls of black-and-white film hanging out to dry after being processed. In the back is what Bowman refers to as the “office.” It’s where all the film developed at Flats gets digitized before being emailed back to clients—about 80 percent of Flats’ business. You’ll often find Flats’ lab manager, Únies González, and lab tech and shop manager Cassie Soler working away in the space.

The colorful entry area to Flats' suite includes kitschy touches like a vintage Kodak light fixture and an old-school vending machine stocked with rolls of film.

Image: Courtesy Jessi Bowman

Bowman likes to think of her creation as a kind of makerspace for local photographers. Although much of her business revolves around developing and digitizing film for enthusiasts of the artform, what really makes the space special is its community darkroom, which is open to both novice photographers and professionals. Bowman offers three tiers of access: A simple day pass is priced at $25, and unlimited monthly access during business hours costs $75 a month. Meanwhile, a 24-hour membership pass is priced at $140 a month.

The darkroom is located behind the building’s kitchen in a small room with heavy black curtains. During a recent visit, 24-hour access member Izaac Costiniano, a budding local photographer, was in the space doing the final wash on a stylized black-and-white photograph of the faded faces of two men, who appeared to be merging into one. Four enlargers used for black-and-white photography, all donated machines, filled much of the space around him. Off in one corner, covered by an additional curtain, was a color enlarger.

Bowman offers three tiers of access to Flats' dark room space, including day passes for $25.

Image: Courtesy Jessi Bowman

While the rest of the room is usually lit by a very faint red light, the color-focused space requires total darkness. Bowman says she’s really the only one who uses it. “You get used to it,” she says of working with zero light. “My boyfriend makes fun of me because I don’t realize how much I do in the dark now. I’ve been working in darkrooms since I was in high school. I’ll be in the kitchen now in the complete darkness and he’ll be like, ‘What are you doing?’”

Jeremy Perez, Flats’ darkroom manager, can usually be found in the space supervising members as they go about their work. Bowman says they make sure everyone who uses the darkroom, even if they’re new to developing photography, knows how to properly use the space. She says that most people who use the darkroom come and go as they work on various projects. Color chemistry isn’t included in any of the passes, but visitors have everything they need for black-and-white chemistry; they just have to supply their own papers and film.

“I want to create a home for artists in Houston,” Bowman says. “We’re one of the major cities, why do artists feel like they have to move away from here? Why can’t we create more outlets and home bases for them?”

Image: Courtesy Nneoma Ajiwe

This well-built-out suite is a far cry from the Flats of a few years ago, when the company functioned mainly as a nomadic gallery space, popping up from time to time for shows in people’s homes. Bowman says she opened that iteration of Flats to make it easier for photographers to show their work locally and to help better foster artistic connection in this vastly spread-out city. “There’s this constant joke that you have to move away from Houston to be able to show in Houston. I think a lot of that is because there are only so many outlets and they’re kind of competitive,” she says. “We’re also all in these pockets, and we don’t know what’s going on everywhere else, so I wanted to bring people to other spaces.”

Bowman's FLAT Files magazine focuses on showcasing the work of photographers from the US's South Central region.

Image: Courtesy Jessica González

Flats’ growth hasn’t ended with the opening of the photo lab and darkroom. In 2021, Bowman launched a photo-centric art magazine under the Flats moniker focused on showcasing the artwork of photographers from the US’s South Central region. And although she’s happy with the space she’s in now, she has dreams of further expansion. She’d love to eventually move into a bigger spot that has room for a dedicated gallery where she can host longer shows. A bigger space would also allow her to open a larger community darkroom, in addition to an expanded classroom area—enough square footage for masterclass programming and an eventual residency program.

“I want to create a home for artists in Houston,” Bowman says. “We’re one of the major cities, why do artists feel like they have to move away from here? Why can’t we create more outlets and home bases for them?”