The Upside of Down

Image: Shutterstock

The sun was out, the air was crisp and the beer was cold. The beautiful Houston fall day felt blissfully uncomplicated. But the subject at the picnic table seemed anything but: the price of oil, and its impact on Houstonians. On that October afternoon, oil was trading at below $47 a barrel, less than half of its peak in June 2014. Was that a good thing or a bad thing for the crowd hanging out with us at the West Alabama Ice House?

“Think about it,” said Lester King, a research fellow at Rice University’s Shell Center for Sustainability. “You’re a consumer. So, I mean, think about it. How are higher gas prices going to benefit you?” We picked at the label of our Dos Equis. He was making a valid point, but still it felt something like sacrilege. Should we even be talking about this out loud? Maybe we should be whispering …

We get it. Average folks in other cities welcome tumbling oil prices, because it means more money in people’s pockets—in 2015, an estimated $750 per U.S. household. But aren’t things a little different in Houston? You know, the Energy Capital of the World?

King laughed a little. “I am quite sure,” he said, “there are not many people who are pumping gas in October and seeing a 50 percent decrease in the bill and saying, ‘Oh my God, I just wish this gas price would go up! This is so bad for the economy!’”

King, whose research focuses on affordability and quality of life in Houston, certainly doesn’t deny that the oil and gas industry has brought prosperity to the entire nine-county region, but he emphasizes that not all locals are affected equally. Of Houston’s 1.8 million jobs, for instance, 51 percent belong to people who live outside city limits. “So high oil prices benefit the region as a whole in terms of more jobs, more distribution companies, et cetera,” he said, “but that doesn’t necessarily mean the city of Houston benefits at the same level.”

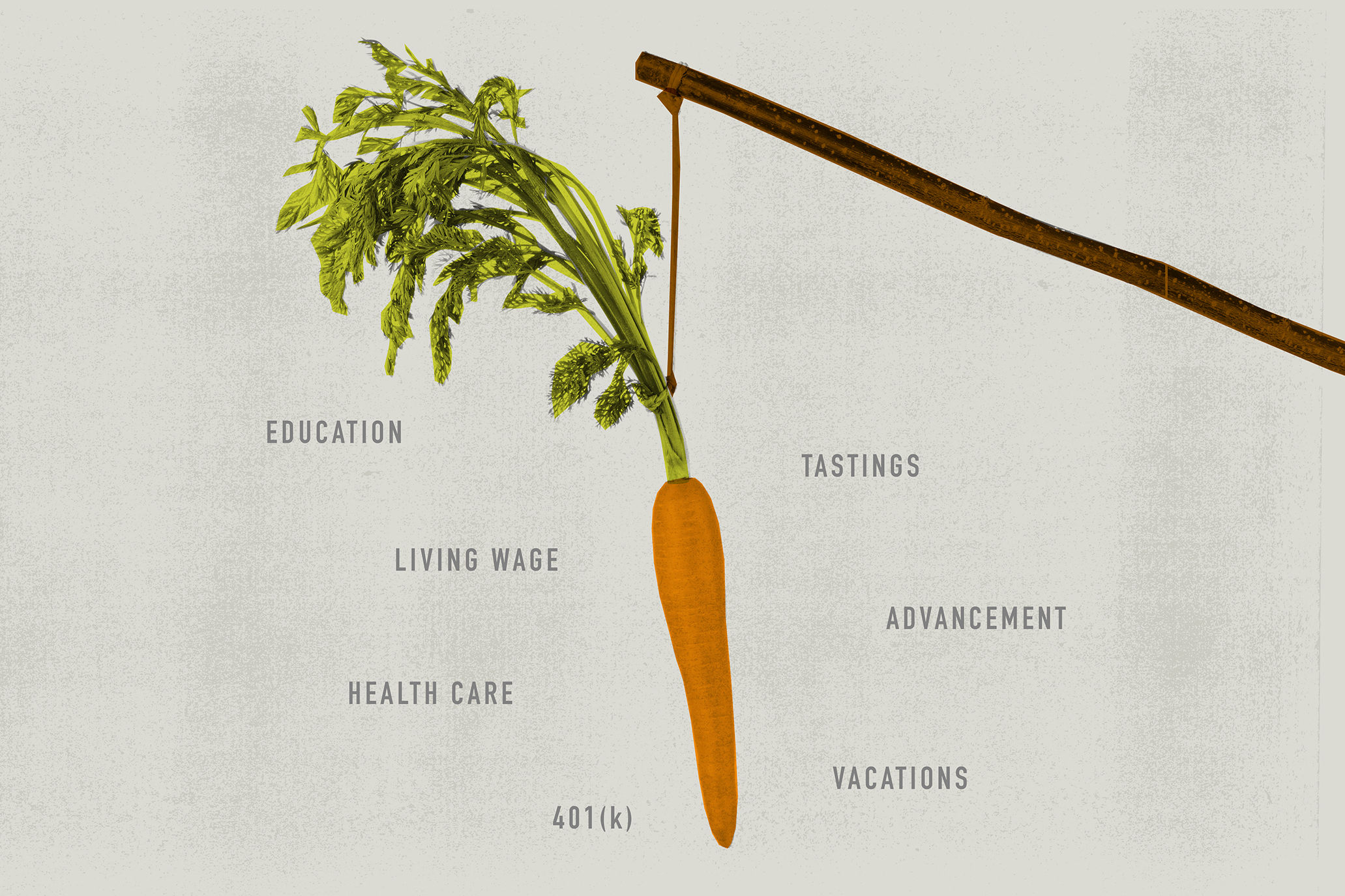

The city itself, he continued, has a higher poverty level than the surrounding areas. And within city boundaries, “the waitresses, the bartenders, the dry cleaning staff—you know, the service workers—whether or not we have oil prices going high or low, they still have their jobs,” King said, explaining that even in a downturn people still go out to dinner. “So they don’t necessarily benefit from higher oil prices.”

In both our city and the broader region, though, if you’re pleased with your smaller bills, you’re probably not going to crow about it. For one thing, nobody’s cheering layoffs or lost business. For another, “Oil and gas has become part of the culture,” said King. “So even if you don’t eat from that pot, you still feel as if you need to support it.”

As for the city going forward, the future is all about diversification—becoming less dependent on oil prices that we’ll never be able to control. “This is 2015,” said King. “You may say, ‘Hey you know, I’m a big supporter of oil and gas—but you, my son? You need to go study nanotech.’”