How Houston Became the Country’s Most Welcoming City for Refugees

Image: Javier Jaèn

Ali Al Sudani knows what it’s like to be a refugee in Houston. When you arrive here—dazed, tired, hopeful, often after a years-long wait in a resettlement camp—you are shuttled from Bush Intercontinental Airport to a small, minimally furnished apartment, typically in southwest Houston, where only the basics await: “One item per family, one spoon, one fork,” he says, emphasizing the “per family” part. “No TV, no microwave, no iron, no computer.”

Whether you speak English or not, you are expected to be self-sufficient within six months. Within eight months, you must begin paying back the cost of your plane ticket. Within a year, you are required to apply for a green card. After five years, you may apply for U.S. citizenship. But that’s a long time away. You’ll spend your first days simply trying to reassemble your life in a brand new country, oceans away from everything you have known.

Today, Al Sudani, a former mechanical engineer from Maysan Province in southeastern Iraq, supervises the refugee services department at Interfaith Ministries, the very same resettlement agency that helped him immigrate to Houston in 2009. But he well remembers the years that preceded his flight from Iraq, the anonymous death threats he received for helping British coalition forces as a translator, and the temporary home in Jordan he occupied while awaiting the arduous review process that would eventually grant him refugee status.

To listen to Al Sudani rattle off the list of agencies that vetted him, the endless acronymic departments that conducted background checks and hours-long interviews—“It starts with a multilayer process for security checks: the DoD, FBI, CIA, DHS, USCIS, different security agencies, one after the other,” he explains—is to exhibit perhaps 1/10,000th of the patience demonstrated by refugees awaiting eventual resettlement.

Refugees have little-to-no say in where they eventually end up. It could just as easily be somewhere in Canada as Harris County, although agencies do try to keep families together. “You don’t get to pick the U.S.,” chuckles Al Sudani at his Midtown office, from which he helps resettle an average of 1,500 refugees a year in Houston, the majority of them Cuban, Iraqi, Afghani, Eritrean, Sudanese, Congolese, Somali, Burmese and Bhutanese.

As for Syrian refugees—the nationality that’s received so much attention of late due to the ongoing European refugee crisis and the recent terrorist attacks in Paris—Interfaith Ministries has helped resettle 25 in Houston since the outbreak of civil war in Syria in 2011, while the U.S. as a whole has resettled only 2,290, compared to the hundreds of thousands flooding across the porous European borders. These are only a few of the many reasons Al Sudani and Houston-based Interfaith Ministries are befuddled by our nation’s intense response to the current Syrian refugee crisis occurring in the Middle East.

Nowhere has that response been more drastic than in Texas, where Governor Greg Abbott threatened to yank funding from nonprofits like Interfaith and the YMCA if they helped resettle Syrian refugees, Attorney General Ken Paxton requested a restraining order against the federal government to prevent Syrians from being resettled in the state, and two Syrian families are now detained after presenting themselves at the Mexican border in Laredo as asylum-seekers—all out of fear that they may have ties to the so-called Islamic State, the terrorist organization more commonly known as ISIS.

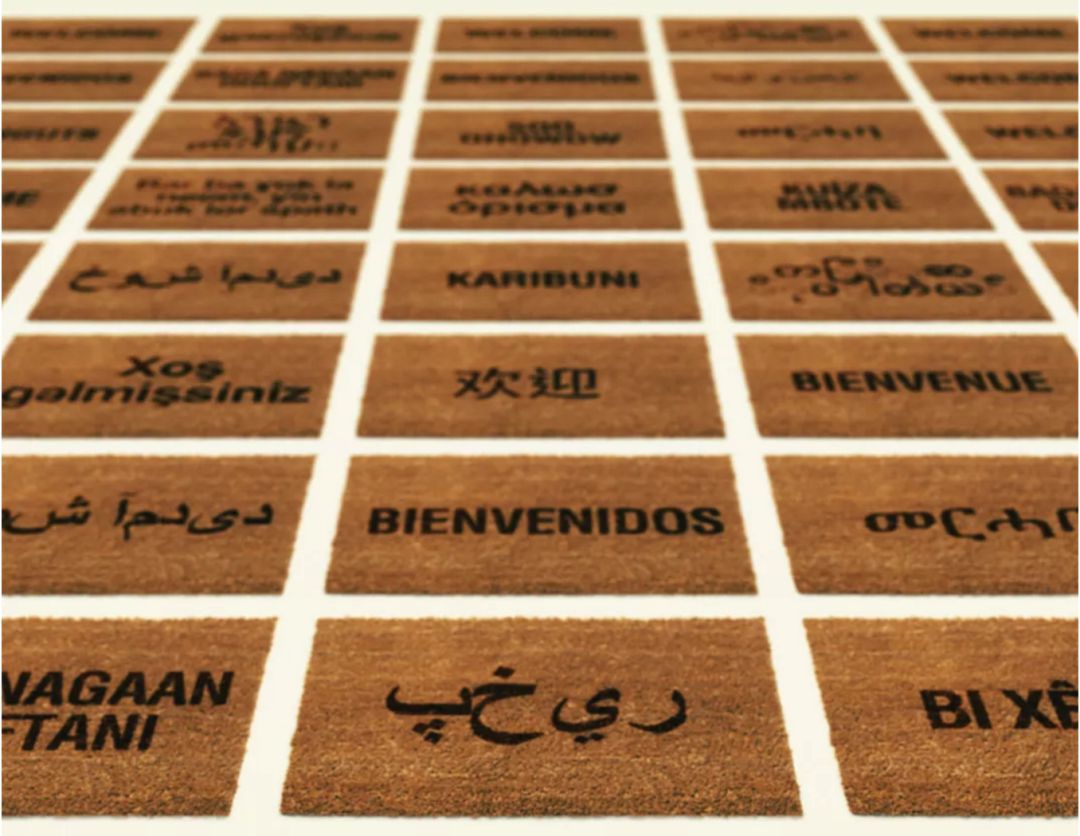

These events stand in stark contrast to Houston’s history as a safe haven for refugees, something that has been recognized internationally ever since 200,000 South Vietnamese “Boat People” resettled here beginning in the 1970s. “Houston is the most welcoming city to refugees,” Al Sudani boasts of his new hometown, which, if it were a country, would rank fourth in the world for refugee resettlement. “We are bragging, we are proud, when we go and have our conferences with other resettlement agencies worldwide,” he says. “Houston is the example of how the community and the agencies provide exceptional services. Houston is the model for other cities.”

This, Al Sudani admits, was unexpected. “My perception of Texas in general was what you see on TV,” he laughs. “My perception was completely wrong. People in Houston are generous, friendly, welcoming. It’s a great city, a great economy, a multiethnic city; you can find different stores, different types of food, and employment is much better. It was a pleasant surprise.”

As for Abbott and Paxton’s efforts to stop nonprofits like Interfaith Ministries, Al Sudani says Interfaith sympathizes with their point of view—to a degree. “We understand that the state government is doing this because of their understanding of the situation, which is not a full understanding.” In the end, the Texas leaders have made little progress, although they have succeeded in stoking fears.

Syrians, Al Sudani emphasizes, not only represent a small fraction of the 85,000 refugees the U.S. is expected to resettle this year, but are also more thoroughly vetted by intergovernmental agencies than any other traveler to the country. “The argument that this program is not well established—I don’t support this idea because I know the program,” he says. “We know that we have a very thorough and complex and rigorous process."

Of course, even the most rigorous process can have imperfections. The news that Iraq-born Palestinian refugee Omar Faraj Saeed Al Hardan was arrested in Houston on January 8, accused of providing material support to ISIS and planning attacks on both the Houston Galleria and Sharpstown Mall, came as a shock not only to Al Hardan’s family—who maintain that they’re ardently anti-ISIS—but to the system itself. According to Department of Justice allegations, Al Hardan lied to officials while seeking his U.S. citizenship, which was granted in 2011.

Though Interfaith was not the agency responsible for resettling Al Hardan, they took the news hard, as any refugee-services organization would. Nevertheless, Al Sudani says, they remain steadfast in their beliefs. “As a faith-based organization, Interfaith Ministries for Greater Houston continues to believe in this country’s tradition of welcoming families fleeing violence and persecution,” communications manager Raequel Roberts tells us in an emailed statement. “Our experience has shown that refugees add to the richness of our communities, making them a better place for all to live.”

The key to overcoming fear, Al Sudani believes, is to understand that “refugees are normal people in abnormal circumstances.” As for Al Sudani himself, he’s now a fan of Italian food, barbecue, and weekend trips to local wineries, and as of November 2014, he’s a proud U.S. citizen. “When they told me I passed, my eyes started to weep,” he says. “When someone tells you now you are a citizen, the idea of being part of this fabric, this mosaic, that you have rights and responsibilities—that’s the beauty of this country.”