So, What Does the Department of Neighborhoods Actually Do?

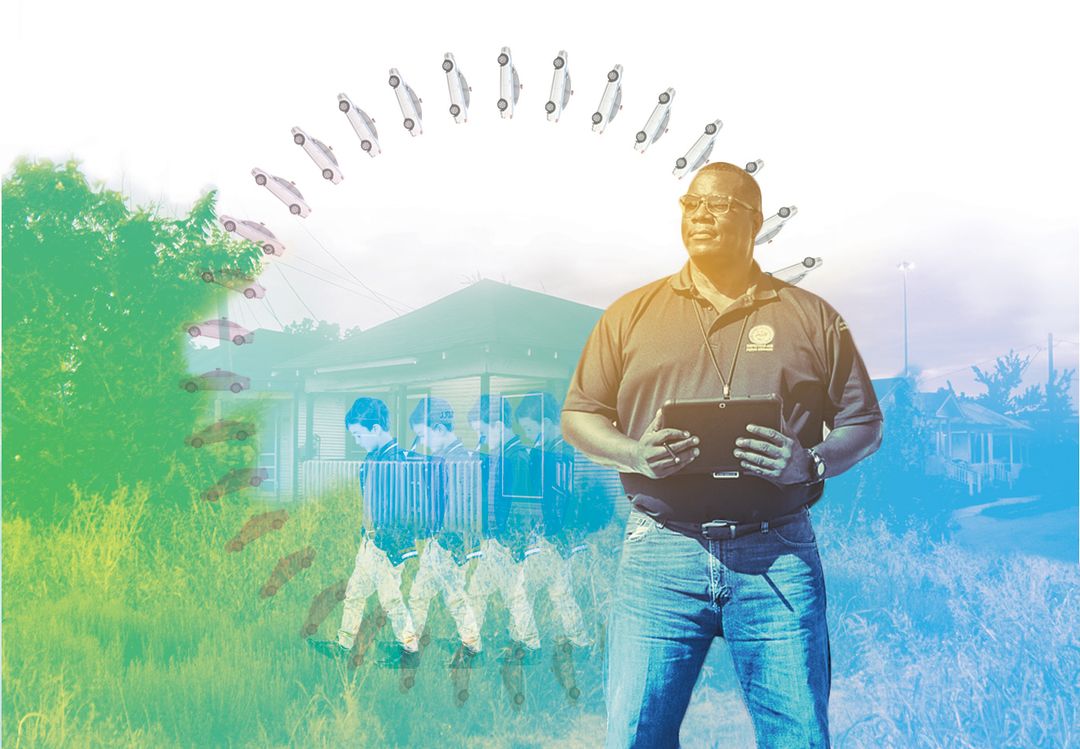

Melvin Hopkins

Image: Michael Starghill, JR.

Melvin Hopkins is an encyclopedia of Houston blight. In the Greater Third Ward, this Department of Neighborhoods (DoN) senior inspector knows the story behind every padlocked home and unruly lot—like the one he shows us, one June morning, on the corner of Adair and Reeves.

“When I learned about this property, there were 22 row houses, [and] they were vacant and open,” he says. “The weeds were high, people started throwing trash and rubbish.” On his rounds, Hopkins would see elementary kids wander by, past drug paraphernalia and uninviting vagrants. Two families had even started squatting, making do without electricity or running water. The owner was absent, the address in the Harris County Appraisal office not current. Through luck and sheer will, Hopkins eventually tracked him down, at a business across town. Turns out the guy didn’t remember he’d bought the crumbling buildings. Hopkins arranged for a visit: “We met right here. And he was like, ‘Oh, my god.’”

This all happened a year ago. Instead of the city abating the entire block, at taxpayers' expense, the owner hired his own contractor and demolished his 22 units. Hopkins canceled part of a planned trip to watch them come down. All that’s left now is a gravel drive, mowed grass, and the prospect of something better.

TaKasha Francis

Image: Michael Starghill, JR.

Sitting in the passenger seat, TaKasha Francis—Hopkins’s new boss—peers out her window and asks a question we shared: “How do you forget you have 22 buildings?!”

City Council confirmed Francis to run the Department of Neighborhoods in March. The lively and animated 39-year-old is a Southwest Houston native, daughter of an HISD cafeteria worker and TSU’s first plus-size queen. (“Who doesn’t want to dress up and wear makeup?” she asks with a smile.) She’s done motivational speaking, self-published a book called The Diva’s Diary (subtitle: “original poetic thought notes and commentary on love and life”), earned a J.D. from the Thurgood Marshall School of Law, and opened her own civil practice. Her hair is stylishly braided, her jewelry sparkly and funky. When Mayor Sylvester Turner—her former law professor—stumped for Francis in the council chambers, he described her as a millennial. (She’s a Gen-Xer, technically.)

DoN, like Francis, is fairly young, having been reorganized and renamed in 2011. Most of its employees enforce noncriminal violations and remedy public nuisances—think overgrown lots, dangerous structures, junk motor vehicles. Hopkins, stocky like a fullback with soft eyes and a pencil-thin mustache, functions like a beat cop. The 19-year-veteran canvasses his assigned “super neighborhood” to identify problem spots, communicates daily with civic and homeowners’ groups (“I always look for the nosiest neighbor on the block”), and helps educate residents about the municipal code. When he has to, he levies citations and fines, from $50 up into the thousands.

Over the years, his workload has jumped: DoN fields too many requests (35,000 in 2015) and has too few front-end inspectors (45) for the land it patrols (620 square miles). As far back as 2014, Francis’s predecessor, Katye Tipton, warned reporters that her agency was overwhelmed and understaffed. And the cavalry isn’t coming: City Hall cut deeper into the department’s funding, by 5 percent, with its FY 2017 budget.

Image: Michael Starghill, JR.

Francis wants to find inefficiencies where they might exist, attract new volunteers, and employ new technology and “unconventional ideas” that could help deliver services more quickly. (A few months into her tenure, she’s still vague about what those ideas may be.) In the meantime, she’s leaning on her preternatural charisma to boost departmental morale. Her inspectors are “super-heroes, swooping in to save the day.” She hugs them when she sees them, reiterating how valuable their work is. “Everybody,” she says of her team, “seems ready for some level of change.”

She points at a pink cottage, farther down on Reeves. The paint is peeling, the windows boarded up. Stray branches and an old toilet have been dumped out front; because he can “see the greenery is still on the tree limbs,” Hopkins knows the pile is fresh. A neighbor from across the street walks over, and Hopkins introduces himself, asks a few questions. “We’re going to get you some relief and have this taken care of, all right?” As he pulls away, he jots a note to check the property records back at the office.

During his career, Hopkins has worked in all four corners of Houston. “Communities have changed,” he says, “and for the betterment of the whole city.” In the Third Ward, he takes pride in the gradual improvements he notices, and the contributions he makes, one property at a time. “You look at it now,” he says, “and you can see the retail and businesses coming up. New homes are being constructed. You’ve got the METRORail that’s cutting through. Code enforcement plays a big role in this.”

Even when he’s on vacation in other cities, Hopkins sees violations. He can’t turn off his inspector’s brain. But he doesn’t really want to, either. “Home is important,” he says. “You put in eight hours of work, you want to come home and relax!”