How, Exactly, Should We Remember George Mitchell?

Near the end of his life, George Mitchell, the legendary wildcatter best known as a champion of fracking, proposed his headstone read “husband, father, ecologist, founder of The Woodlands.”

If those legacies sound contradictory, they are; one of his sons called it “the Mitchell paradox.” By his death in 2013 at age 94, the Galveston-born entrepreneur had worked to save the endangered whooping crane, establish a Houston suburb as a model for green development, and donate hundreds of millions to sustainability causes—all bankrolled by more well-known pursuits toward mastering the environmentally dubious drilling method of hydraulic fracturing.

It’s this complicated figure that former Houston Chronicle business columnist Loren Steffy sought to capture in his new book, George P. Mitchell: Fracking, Sustainability, and an Unorthodox Quest to Save the Planet. The tome marks the oilman’s first comprehensive biography; when Steffy approached the Mitchell family after his death, he was granted access to extensive personal archives on the understanding that the journalist would give Dad a fair shake. “They recognize that their father popularized fracking,” Steffy tells us, “but they also want people to understand the other profound aspects of his legacy.”

Of course, there’s no ignoring his defining achievement, the successful pursuit of a new way to extract energy from the earth. “Let’s face it, fracking had a larger impact on the world than really anything else that Mitchell did,” Steffy says. “It has fundamentally reordered global petro-politics, it’s changed foreign policy, it’s changed the economics of the oil business—you can’t run away from that.”

The book hammers home the wonders the practice has unleashed—shuttered coal plants, $2 gas, 4 million domestic jobs, and, as of 2015, an estimated $2,000 in annual household energy savings—while spending less time dwelling on the practice’s well-known and widespread downsides. One chapter leads with a North Texas family who lived without running water for a decade after Mitchell’s fracking contaminated their groundwater with natural gas. The uptick in earthquakes linked to drilling activity, meanwhile, merits a few paragraphs.

Mitchell didn't invent fracking, but his company perfected it.

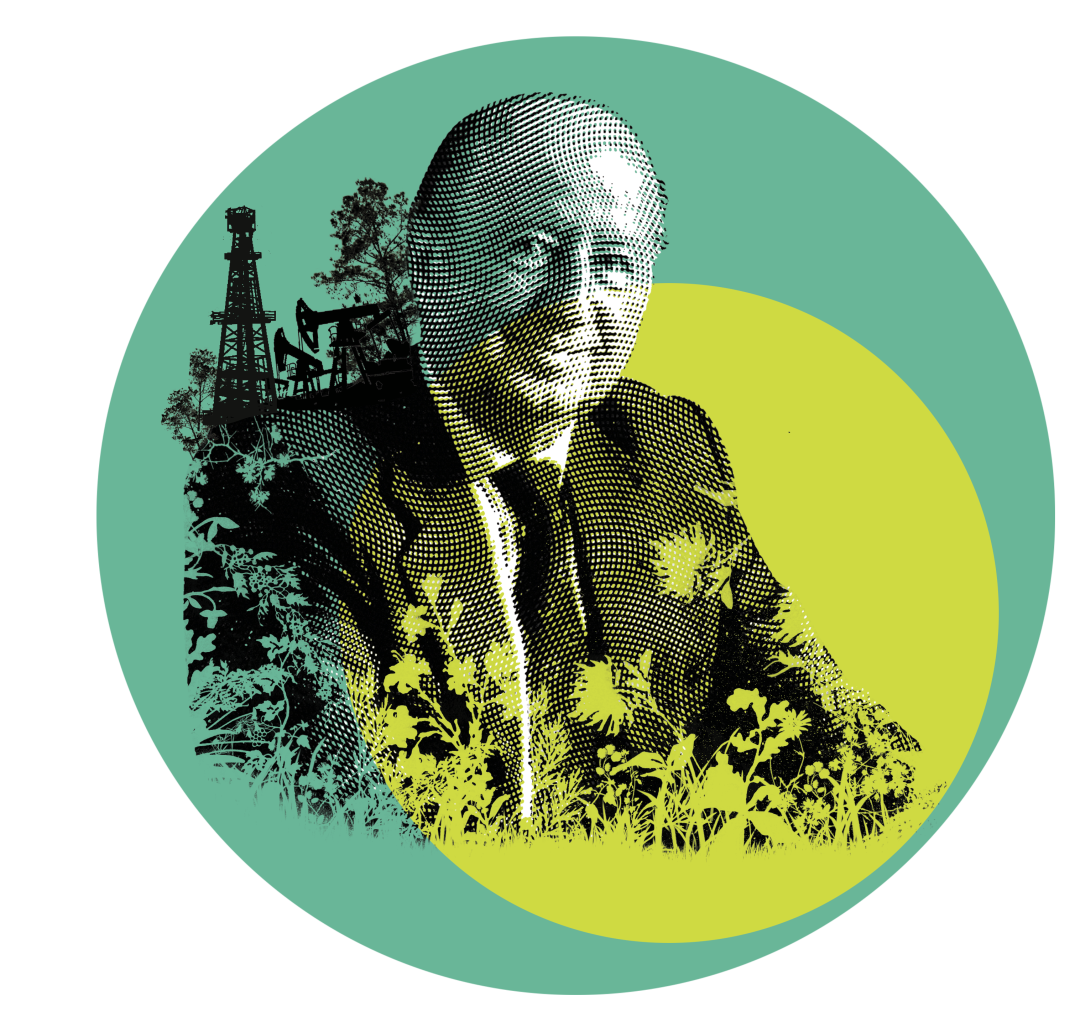

Image: Amy Kinkead/Public Domain

Mitchell’s energy empire began with Oil Drilling Co., which he founded in the 1940s with his brother Johnny and a partner. The brothers had grown up poor children of Greek immigrants who settled in Galveston. Mitchell, who’d studied petroleum engineering at Texas A&M, discovered a knack for finding oil on his way to drilling more than 8,000 conventional wells.

Aspirations well beyond oil quickly emerged as his company—eventually rebranded as Mitchell Energy and Development Corporation—soldiered on as a mid-sized firm. Beginning in the 1960s, Mitchell poured company funds into a new community north of Houston dubbed The Woodlands, built at a loss as a thoughtful, tree-filled rebuttal to the city’s haphazard concrete jungle. The experiment in sustainable development was inextricably tied to the company’s oil business, particularly as energy prices—and therefore profits—skyrocketed amid the 1973 oil crisis. As one real estate executive told Steffy, “The Arabs saved The Woodlands. If we had not had that oil embargo, we might not have survived.”

It wasn’t until the 1980s that he embarked on a project in the Barnett Shale, near Fort Worth, that would make history—and eventually thrust Mitchell into the billionaire’s club. Facing declining reserves in the company’s biggest gas fields, he saw it as a financial imperative to develop new technologies to unlock untappable sources of natural gas. The premise for fracking had existed for decades, but nobody had rendered it economically feasible. His engineers sought to perfect the recipe of sand, water, and pressure necessary to unleash the hydrocarbons locked within shale rock. Competitors branded the billion-dollar pursuit “Mitchell’s folly,” but that changed in 1998, after a Barnett Shale well unleashed a gusher.

As the technique rapidly led to a global shale gas revolution, Mitchell heralded it as a stepping stone to a more sustainable future—and in some ways, it was. Abundant natural gas is a cleaner-burning, less-polluting alternative to oil and coal, one that could both mitigate smog concerns and reduce carbon emissions driving climate change. Whether the self-fashioned environmentalist fully reckoned with the darker sides of his breakthrough, however, remains unclear. Steffy writes that by the time Mitchell sold his company in 2001, he had never physically visited his fracking sites and bitterly fought lawsuits from homeowners affected by company drilling.

How to square that with the man whose estate has so far fulfilled his pledge to donate the majority of his wealth? Who, among many other things, revitalized Galveston’s historic Strand District, established a lab-mice breeding program to assist cancer researchers facing a shortage, and funded the Giant Magellan Telescope, a next-generation wonder still under construction in the Chilean desert? You can’t, beyond recognizing that Mitchell Energy profits enabled all of these endeavors. And that, according to Steffy, was always the plan.