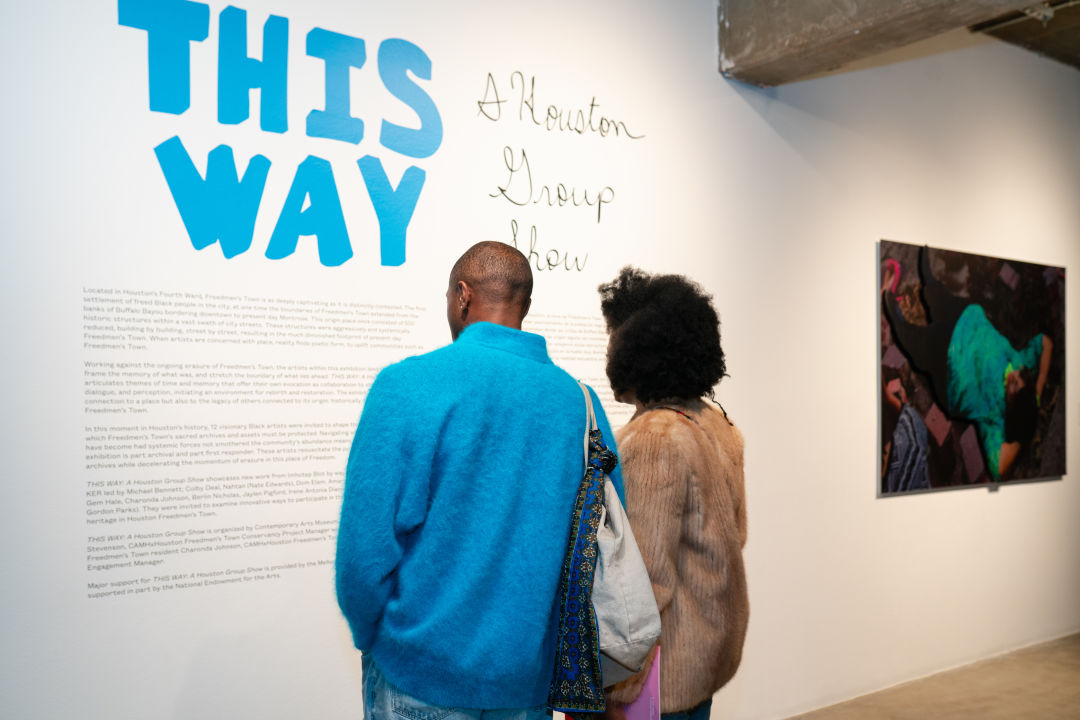

A New Exhibit Examines the Memories of Freedmen’s Town Through Art

This Way is on show at the Contemporary Arts Museum Houston until March 17.

On December 15, 2014, residents of Houston’s Fourth Ward and its surrounding areas found themselves at the heart of a battle that would be pivotal in preserving the heritage of a historic Houston town. The battleground was not one of conventional warfare, but rather a protest over the streets of Freedmen’s Town, a community built by and for formerly enslaved peoples after the Emancipation Proclamation in the late 1800s, where the echoes of the past clashed with the forces of urban development.

The catalyst for this clash was a controversial decision to remove bricks from the historic streets of Freedmen’s Town. Over a century old, they serve as a tangible reminder of the area’s rich African American history, one deeply embedded in the soil of this settlement in the heart of Fourth Ward.

A new exhibit by the Contemporary Arts Museum Houston (CAMH) tells the stories of resilience within Freedmen’s Town, such as that fateful protest that took place almost a decade ago. Titled This Way: A Houston Group Show, on show until March 17, 2024, the groundbreaking exhibition showcases the struggles, triumphs, and vibrant history of this African American neighborhood through the eyes of 12 talented Black artists.

This Way is a collection of photography, video, paintings, sculptures, artifacts, archives, and more.

This Way brings forth narratives of people like Priscilla T. Graham, who was present at the fight to save the streets in 2014, to share the importance and current realities of Freedmen’s Town through various artistic expressions.

Walking into the exhibit at CAMH, visitors are greeted with black see-through walls strategically placed throughout the gallery. The transparency of the exhibit, both metaphorically and physically, echoes the openness of the community, its stories laid bare for all to witness.

A video of a young man holding onto a brick floating upwards plays on a loop in the small theater at the center of This Way.

One piece at the center of this narrative is a photograph by Graham, taken in 2014, which captures a moment of defiance and serves as a catalyst for the exhibit. The image features Doris Ellis, a prominent community leader, laying her body on the broken-apart brick streets.

“Forty-five bricks were removed from that spot and it was just enough for her to lay her body,” Graham recalls of the day when the city tried to remove the century-old flooring. “It is a coffin-like symbolism. When you look at [the display] you think she’s floating out of the bricks to give you that illusion.”

Doris Ellis lays down among the historic bricks.

The decision to remove the historic bricks was met with widespread opposition from the residents as those streets, once laid and trodden by the formerly enslaved peoples and their descendants, held an irreplaceable cultural significance. The removal was seen not just as an act of urban development but as an erasure of history, a disconnection from the roots that had sustained Freedmen’s Town through decades of change.

“This exhibit is groundbreaking and it’s a representation of that community,” Graham says. “We all get to see that memory and it touches something special inside of you that you experienced as a child or as an adult in your community.”

A narrator recites poetry over the short film about preserving the Freedmen's Town streets.

The exhibit doesn’t merely showcase the struggles to save the memories of Freedmen’s Town, it also invites visitors to immerse themselves in the multifaceted layers of its history. A mini settlement structure captures the layout of the town during its first decades of inception combined with how it looks today. A pyramid-like brick sculpture made with wax includes words and phrases representative of the area written underneath each item.

And a movie made by the artists offers a unique perspective to the collective narrative of town: A young man holds onto a brick as it floats upwards, himself being carried away by it, but two even younger residents hold onto his legs—just enough to avoid him and the brick leaving for good.

Old photographs of Freedmen's Town and its residents are printed on textiles and hung on a drying line with clothes.

Some of the works in the display also explore former businesses that have contributed to the fabric of the neighborhood and the city of Houston in general. A piece by local DJ and ethnomusicologist Flash Gordon Parks recreates The Ebony Bar, a tavern that served the area from the 1950s to the 1970s. The place was owned by the father of Wayne Johnson, a drummer in the music group Masters of Soul, and played a role in proliferating artists of color in Houston.

The Ebony Bar is a piece of Houston history that's on display in This Way.

Gordon says his piece, which included images obtained from the owner’s descendants, a cash register from when the location was in operation, and a replica of portions of the bar, pays homage to the legacy of a place that meant a lot to the city.

“I thought it was really important to tell that story because the Johnson brothers have a foothold in Houston music history,” Gordon says. “I [wanted to] be able to honor that history and tell that story that a lot of people, unless you grew up during that era, probably wouldn't know.”