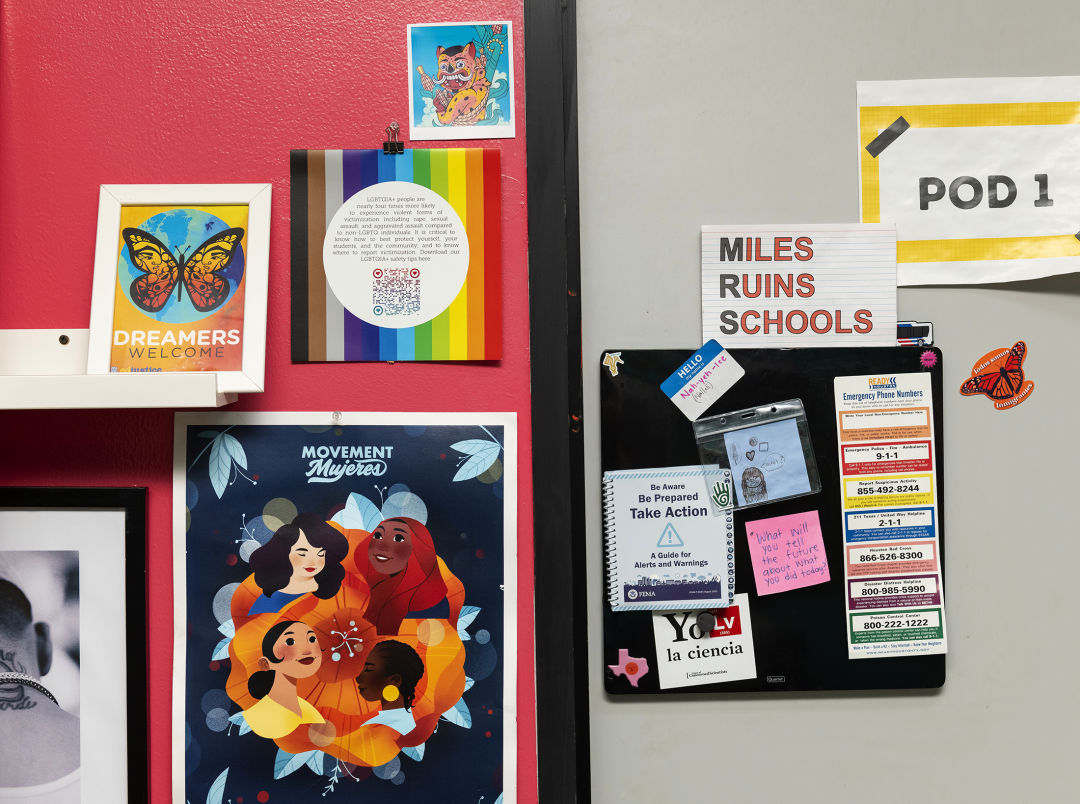

Two Years into Mikes Miles’s HISD Tenure, Parents Are Still Mad

Image: Anthony Rathbun

Libraries aren’t libraries anymore. Books are gone, replaced with desks crammed so tightly together that students have to shuffle sideways to find a seat. The Houston Independent School District calls these spaces “Team Centers,” where high-achieving students supposedly go to work on advanced tasks—often just more packets—while those who fall behind stay in their original classrooms for remediation.

Books are not the only things missing. Gone, too, are the small moments of discovery a library can spark—those unplanned conversations about new authors, the pride in finishing a thought-provoking book. Instead, students file in and out of these repurposed spaces with packets under one arm, a timer ticking down each segment of their day. This is the reality in several of HISD’s New Education System (NES) schools, a model implemented under Superintendent Mike Miles to transform struggling campuses.

Since June 2023, HISD has undergone a sweeping transformation that began with a state takeover and Miles’s appointment. Citing low performance at several campuses, the Texas Education Agency replaced the elected school board with state-appointed managers. A year and a half later, a proposed $4.4 billion bond, pitched as a fix for decades-old buildings and crumbling infrastructure, was voted down by Houstonians in November, leaving many structural needs unaddressed. Meanwhile, under Miles’s NES, certain campuses received top-down directives—rigid schedules, multiple daily timed tests, strict behavioral rules, and newly repurposed libraries—while teachers and parents report a steep drop in academic flexibility, extracurricular programs, student vigor, and wraparound supports.

Mary Davis, a veteran English teacher at one NES high school (whose name was changed for this story due to fears for her job security), describes days filled with meticulously timed slides, packets for every lesson, and barely a moment to let students voice a question or linger over a new concept.

“They’re expecting kids to be like robots,” she says. “[Teachers are] given slide decks, student activity packets—basically a whole bunch of worksheets stuck together—a test [students] have to take within 10 minutes, and then a follow-up activity sheet set. There’s nothing that ever comes from us.”

That script has become a defining feature of NES schools under Miles: a prescribed, minute-by-minute approach that leaves little room for spontaneity. Critics say it prevents children from developing a genuine love of learning.

Houstonia reached out to HISD for comment, but the district did not respond.

The parents are sick of it.

On February 5, families from across Houston showed their frustration by participating in a “sick-out.” During the protest, organized by local nonprofit Community Voices for Public Education (CVPE), parents either kept their children home for the day or withdrew them right after attendance. In Texas, schools receive funding based on Average Daily Attendance (ADA), so each absent or withdrawn student directly impacts HISD’s funding. The message was clear: Parents want the district to feel the financial sting of their dissatisfaction.

According to CVPE organizers, more than 1,000 people across 149 schools officially signed up for the sick-out, with many others quietly keeping their children home. Some parents hesitated to pledge in writing but still kept their kids out for the day.

At one of CVPE’s offsite locations, the Texas Environmental Justice Advocacy Services center, some children gathered to spend their sick-out morning learning through storytelling, gardening, and creative arts. They had snacks and lunch available. There was also a pop-up math lesson led by Sophie Grace-Rojas, a sixth-grader who recently changed schools after witnessing the NES model firsthand. Meanwhile, another group headed to Montrose for an art outing, including a visit to the Menil Collection and a short trip to a neighborhood library.

Image: Anthony Rathbun

Grace-Rojas’s mother, Jessica Campos, had watched her daughter struggle under the NES model at both Pugh Elementary and Project Chrysalis Middle School. She’s now an organizer with the CVPE, and helped coordinate the sick-out, fueled by her experiences navigating the system as a parent. Campos says her daughter had once made slow but steady progress in reading, finally moving from six letters behind her peers to just two—a milestone that meant she didn’t have to attend summer school. Then, NES arrived.

“Before the NES system happened at Pugh Elementary, Sophie was already struggling. She had been struggling with dyslexia all her life, and the year prior was the first year she had shown some improvement,” Campos says.

At the start of the 2023–2024 school year, Miles launched the NES system with Pugh Elementary as one of the 28 schools first included. The structure of Grace-Rojas’s school days changed overnight. NES implemented rigorous schedules and individual learning plans gave way to standardized, one-size-fits-all lesson packets. The progress she had worked so hard for began to stall with the small privileges that helped her dyslexia now gone.

“We lost certified teachers, and then they turned our libraries into detention centers,” Campos says. “At first, this was only happening in our Latino and Black communities. It wasn’t until we all started to make a big fuss about it being just [us] affected that they started forcing other schools to participate.”

Image: Anthony Rathbun

Campos later enrolled her daughter at Project Chrysalis, but she found the same strict routines and daily timed quizzes. When Grace-Rojas began attending a non-NES middle school, Campos says the change was immediate: She was reading more and dealing with less anxiety. Yet, Campos worries for families who remain in NES schools or cannot afford to relocate. She’s not alone. Fred Woods, a third-generation HISD alum and father of a first-grader at Crockett Elementary, shares many of the same concerns.

Woods’s daughter attends an NES-aligned campus, where the shift to a highly regimented curriculum has begun. He calls it “test prep boot camp,” describing how teachers must follow strict scripts, and even first-graders face repeated multiple-choice packets. Mostly, he fears for the future of students who don’t fit neatly into the system’s expectations.

“No test can tell me how anyone is going to do in life,” Woods says. “There’s no correlation between any test—STAAR, SAT, PSAT—and how successful you will be in life. Setting it in students’ heads early that a test governs how successful you are, who you are, or how well you can do, sets them up for failure.”

His concern deepens when he thinks about the socialization skills young children need. The structure of NES limits time for creativity, collaboration, and even simple peer interaction, which is especially detrimental as younger kids don’t have the maturity to sit still for hours and absorb a flood of new information before immediately being tested on it.

“Teachers don’t have the flexibility anymore,” Woods says. “They were able to review things. They had more time to focus on the kids that needed more attention. [Now], they have to stick to the script.”

Teachers can’t actually teach.

The NES model doesn’t just impact students—it’s reshaping what it means to be a teacher in HISD. For Davis, the changes have stripped away her autonomy and ability to meet students where they are. “At the beginning of the year, we’re told to adhere to the slide decks exactly. You can’t take anything out. You have to get through it in minutes,” she says.

Teachers are also giving lessons from poorly designed materials riddled with errors. Davis says she often has to correct AI-written content on the fly, adding another layer to the mental gymnastics now necessary in her role. Then, there’s the added stress of constant surveillance.

“There’s a camera in my classroom [and] an open Zoom link—fuck security. They don’t trust teachers. When we [ask] about privacy and security for children? They’re like, ‘the benefits outweigh the consequences.’ And I’m thinking, ‘consequences to who?’ The consequences come to the families and the children,” Davis says, adding that the kids in her predominantly Hispanic school feel the tension more than ever with the political climate, and constantly fear deportation.

Davis says her classroom door must remain open at all times (allowing administrators to walk in at any moment to monitor instruction). Bathroom breaks are restricted to tightly controlled windows, and even minor deviations from the scripted curriculum can result in write-ups or reprimands. She is also prohibited from assigning reading materials that have historically encouraged students to explore diverse perspectives. She recalls an experience teaching an edited version of Amy Tan’s Mother Tongue to her ESL students. While the changes simplified the language for beginner students, Davis says the edits stripped the passage of its nuance, removing the very elements that made it relatable to them.

“They basically read a really simple story about a kid who was ashamed of their culture and their parent because they spoke broken English,” Davis says. “Mind you, this is all [for] kids who don’t speak English.”

Image: Anthony Rathbun

But is the system working?

That depends on who you ask. Cary Wright, the CEO of education nonprofit Good Reason Houston, which works with HISD and other school districts, says the NES model has generated measurable improvements in overall student attitude.

“[HISD] dramatically reduced the incidence of student discipline issues on campuses,” Wright says. “There’s been a deeper emphasis put on instruction, and much of the school day has become more structured in service of that objective, which has put in place more routines, procedures, and expectations on campuses that have kept students more focused on learning.”

Wright is concerned about the long-term implications of operating on a limited budget. With the proposed $4.4 billion bond rejected by Houstonians, HISD is forced to do more with less. “Costs are going to keep going up as infrastructure continues to atrophy,” he says. “The district will not be able to address many of the needs without that critical source of funding.”

The bond was defeated largely due to the “no trust, no bond” messaging of the main opposition movement. During election season, in neighborhoods across Houston, anti-Miles yard signs seemed almost more prominent than signs for either presidential candidate. About 58 percent of voters cast their ballot against the measure. Parents like Campos, who voted against the bond, say Miles has given them no reason to trust that the funds would have addressed real needs.

“We can come up with a bond together under the right administration,” Campos says. “There’s a lot that is needed. I just don’t think it was the right people to give the money to, especially with what they’ve shown us so far—with us losing wraparound specialists, custodians, so many teachers.”

With protests, sick-outs, and passionate community meetings underway, the future of HISD—and the New Education System—hangs in the balance. For now, teachers like Davis, parents like Campos and Woods, and students continue to fight for better learning conditions as the district remains in a state of transition.